Myths and misconceptions about the original gunpowder abound.

Why would anyone want to use old-time blackpowder, when there are so many cleaner-burning blackpowder substitutes on the market?

Heck, some muzzleloading rifles can even use smokeless powder, the original blackpowder substitute, so why put up with the all the problems of the old-fashioned stuff?

You know the complaints: Blackpowder burns dirty, making guns hard to clean. It rusts gun barrels, and is hard to ignite, especially in damp weather.

Some people just like to use the real thing, especially with older guns or their reproductions. This may seem weird to some hunters, especially those who share the natural human tendency to push technology to the limit (the reason we have scoped muzzleloaders that use smokeless powder).

To other people, part of the pleasure of using a Hawken or Sharps rifle involves stepping back in time: A modern Sharps reproduction might be perfectly safe when used with smokeless powder and jacketed bullets, but that’s not the way hunters in the 1800s did it.

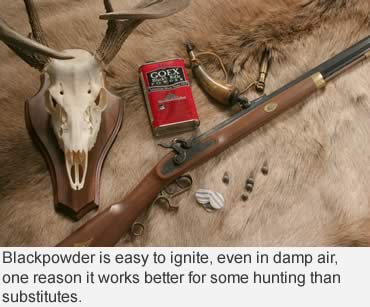

Some of the things modern hunters assume about real blackpowder simply aren’t true. One myth is that real blackpowder is hard to ignite. In fact, the opposite is true.

The reason most of us don’t use real blackpowder these days is that it’s relatively easy to ignite, making it more hazardous to transport and store. This is one reason why smokeless powder was developed, and why blackpowder substitutes such as Pyrodex started to appear a century later. And Pyrodex is indeed harder to ignite.

The easy ignition of real blackpowder makes it less of a hassle for hunting, especially in the traditional muzzleloaders many hunters still use.

The easy ignition of real blackpowder makes it less of a hassle for hunting, especially in the traditional muzzleloaders many hunters still use.

Blackpowder is just about essential when shooting a flintlock. There’s no real substitute for the fine FFFFg powder in the pan of a flinter, and using real blackpowder as the main charge also helps a lot.

Even in a percussion gun, real blackpowder will go bang more consistently than some substitutes, particularly in damp weather. One of the myths of blackpowder is that it’s hygroscopic, meaning that it picks up moisture from the atmosphere. This isn’t so, but the myth probably grew out of the fact that the fouling from blackpowder is very hygroscopic, and also caustic. This is why leaving the fouling in a barrel very long in a damp climate causes the bore to rust—but blackpowder itself is resistant to atmospheric moisture.

One fall I hunted whitetails in western Kentucky with my Thompson/Center Hawken .50-caliber percussion rifle. The weather was damp, with occasional rain and snow. I kept the lock of my rifle protected with a leather cover, and worried about the effect the dampness might have on ignition. There was no reason to worry: When I finally got a shot four days into the hunt, the powder went bang right away. Only liquid water “kills” blackpowder, the reason I kept the lock covered.

As with smokeless powder, blackpowder burns at different rates, controlled by the size of the granules. In North America, blackpowder comes in various designations from FFFFg (or 4Fg) to Fg.

The finest is 4Fg, the powder normally used for priming flintlocks. Very small charges of 4Fg are loaded in small-bore handguns as well. FFFg is meant for handguns or very small-bore rifles, while 2Fg (or the similar 1 1/2 Fg) is most often used in .40- to .50-caliber rifles. The largest size, Fg, is reserved for cannons or extra- large-bore shotguns or muskets.

More than granule size affects the quality of blackpowder. The blackpowder used in firearms is a combination of potassium nitrate, charcoal and sulphur. Potassium nitrate provides the oxygen for the burning of the fuel in the charcoal and sulphur. The sulphur lowers the temperature of ignition and speeds up the burn. Only about half of the powder turns into gas. The rest is left in the bore as fouling or blown out as smoke.

More than granule size affects the quality of blackpowder. The blackpowder used in firearms is a combination of potassium nitrate, charcoal and sulphur. Potassium nitrate provides the oxygen for the burning of the fuel in the charcoal and sulphur. The sulphur lowers the temperature of ignition and speeds up the burn. Only about half of the powder turns into gas. The rest is left in the bore as fouling or blown out as smoke.

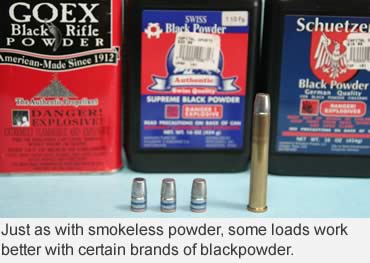

The consistency of the burn is affected quite a bit by the quality of the charcoal, and even the type of soft wood used to make the charcoal. In general, the higher the quality of the charcoal, the more accurate the powder will be, and the less fouling is left behind (though blackpowder is never really clean-burning). Luckily, several good brands of blackpowder are available.

Sporting blackpowder also has the virtue of being a “low explosive.” When it burns, the particles expand at subsonic speeds. (A “high explosive” such as TNT expands at supersonic speeds.)

Under normal circumstances, blackpowder doesn’t produce enough pressure to blow up a steel barrel.

“Normal” means the powder is compressed slightly, with no air space between powder and projectile.

When loading a muzzleloader, the bullet should be firmly pressed into the powder charge.

When loading a blackpowder cartridge, the base of the bullet must slightly compress the powder. This is why blackpowder isn’t normally weighed when loaded in cartridge cases. Instead, enough powder is poured into the case to reach just above the base of a seated bullet.

Quite often a wad is also inserted between the bullet and the powder. This is nothing more than a thin sheet of some light, stiff material, such as the coated cardboard from a milk container, cut into a disc slightly larger than bore diameter. The card wad mostly keeps the lubricant from a cast bullet from migrating into the powder, especially during warm weather when the lube can melt.

In theory, the cardboard also insulates the base of the lead bullet against the hot gas of burning powder.

In theory, the cardboard also insulates the base of the lead bullet against the hot gas of burning powder.

Some shooters use two discs with extra lubricant between them. This supposedly leaves the powder fouling softer and easier to remove, but I’ve shot a bunch of cartridges with nothing between the powder and bullet, and never noticed much difference.

There’s also no reason not to use jacketed bullets with blackpowder, especially in some cartridges. The .32 Winchester Special, for instance, was designed to be loaded with either black or smokeless, and early .32 Specials often had a flippable rear sight to compensate for the different point of impact of the two loads.

I once experimented with a Winchester Model 94 in .32 Special, loading both cast and jacketed bullets with 3Fg Goex blackpowder. Accuracy was good enough to take deer out to 100 yards with either bullet, as was the muzzle velocity of 1,500 fps. Another modern myth is that 3,000 fps is required to kill a deer.

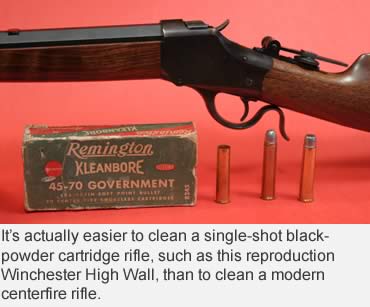

As for cleaning, yes, in a lever-action rifle, blackpowder can be a bit of a pain, but it’s easily washed out using warm soapy water. With a muzzleloader, you just take the barrel off and run soapy water down the muzzle, push a bore brush back and forth a few times, then run plain hot water down the barrel.

The easiest blackpowder rifle to clean is a falling-block rifle like a Sharps, Winchester High Wall or Remington Rolling Block. With the action open, the black gunk is easily pushed out of the muzzle with a wet patch wrapped around a bore brush. After that, push a lightly oiled patch downbore, and you’re done. In reality, it’s a lot less of hassle to clean a single-shot blackpowder cartridge rifle than it is to clean a modern centerfire.

Read More Articles by John Barsness:

• Troubles with Choke Tubes: All sorts of things prevent shotgun chokes from doing what we expect of them.

• The .30-06 Just Plain Works: Many of us know intellectually that the .30-06 is a good all-around big game cartridge, but explanations are not experience.

This article was published in the July 2010 edition of Buckmasters GunHunter Magazine. Subscribe today to have GunHunter delivered to your home.