All sorts of things prevent shotgun chokes from doing what we expect of them.

Two pheasant hunters stood together, looking down at a creek bottom. A stiff November wind bent the willows and cattails along the creek, places where roosters might hide. The taller hunter turned to his companion and said, “I’m changing to full choke. That wind is going to make the birds wild!” He started unscrewing the choke from his shotgun barrel.

How many of us have done something like that in the past quarter century or so, since the screw-in choke tube became more or less standard in new shotguns? And how many of us actually knew what we were doing?

Interchangeable shotgun choke tubes are one of the great inventions of the late 20th century, not just because they greatly increase the ability of the average shotgunner to actually hit flying objects, but because they fill the same shotgunner with faith and hope.

Thus, they also help sell shotguns, and sales are the other half of any great invention. Indeed, choke tubes have become so essential in the average shotgunner’s mind that it’s difficult to sell a shotgun with fixed chokes — yet I’d bet a case of premium 12-gauge ammo that 95 percent of wingshooters have never patterned the choke tubes of their shotgun.

Well, why would they? Doesn’t each tube come with markings that indicate improved-cylinder, modified or full? Simply screw in the tube best suited to the day’s hunting.

This just might work, though as much by pure luck as design. All sorts of things can prevent choke tubes from doing what we expect of them.

This just might work, though as much by pure luck as design. All sorts of things can prevent choke tubes from doing what we expect of them.

The first problem is the definition of the common chokes themselves. Ask the average hunter what improved-cylinder means, and the answers might run from “a wide shot spread” to “I dunno.”

Perhaps not so oddly, this is pretty much the same answer we might get from a shotgun manufacturer, though it might put it in more technical terms such as “10 points of constriction.” In theory, this means that their improved-cylinder choke has 10 thousandths of an inch (.010 inch) of constriction. It doesn’t mean that the improved-cylinder choke of any other manufacturer has 10 points of constriction.

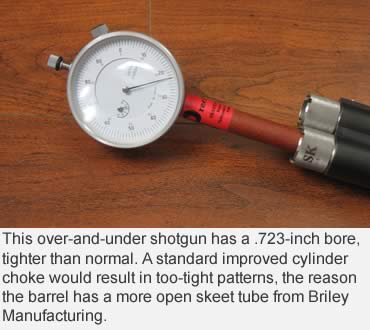

It also may or may not be true. While the choke itself may be .010 inch smaller in diameter than the nominal .730 inch of a 12-gauge bore, the internal diameter of your particular 12-gauge’s barrel may be somewhat larger or smaller than .730 inch. I’ve measured shotgun barrels for many years, in the process discovering 12-gauge bores measuring .720 inch to .743 inch.

This may not sound like a big deal, but the most important thing is not the diameter of the choke itself, but the difference between the bore and the choke. A so-called improved-cylinder choke with .010 inch constriction theoretically should have an inside diameter of .720 inch. But screw it into a .740-inch 12-gauge barrel, and the difference between the bore and choke doubles to .020 inch. This much constriction produces considerably tighter patterns.

It also seems that two shotgun makers agree on the exact constriction of improved cylinder, modified and full chokes. This is partly because ammunition has changed considerably since the mid-19th century, when choke was developed. Back then, shot was all very soft lead, and it took a lot of choke to bunch soft shot together in the air.

By the late 19th century, shotgun makers in Great Britain had settled on what they called quarter, half and full chokes. Full was the maximum choke constriction that would tighten patterns with soft shot, about .040 inch. A tighter choke would actually cause patterns to open up again, because so many pellets were seriously deformed.

Half-choke was thus .020 inch, providing a somewhat larger pattern; quarter-choke was .010 inch, resulting in an even wider pattern.

Half-choke was thus .020 inch, providing a somewhat larger pattern; quarter-choke was .010 inch, resulting in an even wider pattern.

Americans naturally wanted to be different than the British. We called half-choke “modified” and quarter-choke “improved cylinder,” since it resulted in the slightly tighter shot spread than cylinder (no choke at all).

These chokes normally resulted in a certain percentage of the shot charge landing within a 30-inch circle at 40 yards. Full choke averaged around 70 percent, half-choke/modified around 60 percent, and quarter choke/improved cylinder around 50 percent. These facts were understood by almost any avid shotgunner, and didn’t vary much until ammunition changed.

The first change was harder lead shot. Lead can be hardened by the addition of a small amount of other metals, especially antimony. Harder shot deforms less during its trip down the barrel, so doesn’t spread as widely as soft shot. Less choke is then needed to create an effective longer-range pattern.

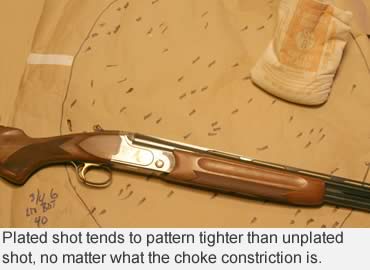

The second change was plated shot. Winchester’s Lubaloy shot, plated with copper, came along in the 1920s. Contrary to what many shotgunners believe, plating doesn’t harden shot as much as it smooths (“lubricates”) the surface, hence the name Lubaloy. Hard plated shot flows more easily down the barrel and through the choke, so it tends to pattern even tighter.

The next big change occurred in the 1960s, when plastic shot-cups became standard in shotshell ammunition. Prior to that, most shotgun ammunition used simple, cylindrical wads behind the shot to seal the powder charge. This meant a lot of shot actually scraped against steel during the trip down the bore, deforming those shot pellets. The shot cup prevented this scraping, and patterns got a little tighter yet.

Eventually, other types of metal were used for shot, starting with iron (steel) after lead shot was banned for waterfowling. Today, new varieties of nontoxic shot appear every year. Many are harder and heavier than lead, so they pattern even tighter.

The end result is that the old British standards of choke no longer apply to the patterns of most modern shotshells. Even the cheapest lead-shot ammo sold in stacks at Wal-Mart contains shot with at least some antimony, and this shot is contained in a plastic shot-cup, so patterns tighter than the best ammo of a century ago. Yet I still run into shotgun “authorities” who claim that modified choke means .020 inch of choke constriction.

The end result is that the old British standards of choke no longer apply to the patterns of most modern shotshells. Even the cheapest lead-shot ammo sold in stacks at Wal-Mart contains shot with at least some antimony, and this shot is contained in a plastic shot-cup, so patterns tighter than the best ammo of a century ago. Yet I still run into shotgun “authorities” who claim that modified choke means .020 inch of choke constriction.

Well, if thinking like a 19th-century Englishman makes them happy, then why not? But I have patterned several different brands of modern shotshell ammo containing hard plated shot that will place 70 percent of the charge in a 30-inch circle at 40 yards with only .012 inch of choke constriction. This is full-choke performance with a choke that some manufacturers call improved cylinder.

With a lot of modern ammunition, many modern shotguns will shoot full-choke patterns of at least 70 percent with all three choke tubes supplied by the manufacturer. This makes changing to the full tube on a windy day of pheasant hunting mere wrist-exercise. It also means that changing to the choke marked IC when hunting ruffed grouse in heavy cover might result in quite a few misses due to a super-tight pattern.

This effect is exaggerated with many of the super full turkey chokes on the market today. These will indeed put more shot into a gobbler’s head and neck, but only if the pattern lands there.

One basic rule of choke is that the tighter the choke, the more erratic the pattern from shot to shot. I’ve patterned turkey chokes that worked fine on the first shot, putting 20 or more No. 5 shot into a typical turkey head target at 40 yards. But the next shot sometimes didn’t put any shot in the target, and not because I didn’t aim correctly. Instead, the tight pattern shifted a foot. This is why I often hunt turkeys with the boring old full-choke tube that comes with the shotgun: It still places plenty of shot in a gobbler’s head and neck, and puts it into the same place every time.

Not all choke tubes are straight. The threads can be cocked a little sideways, resulting in a pattern that doesn’t go where the shotgun is pointed.

While working on a shotgun book a few years back, I tested a lot of different guns at a local sporting clays range. One morning, I received a nifty little over-under.

Normally, I pattern every shotgun before trying to hit flying objects, but this time I couldn’t stand it and took the little gun to the range with the improved-cylinder and modified chokes in place.

By the end of the round, I was talking to myself. I’m a decent clays shooter, but missed some easy shots while powdering other targets that came out of the same trap. The mystery was solved when I finally shot the over-under at some pattern paper. The upper barrel placed the center of its shot spread about 2 feet high at 25 yards because of a defective choke tube! The other tubes shot right where the gun pointed, explaining why I hit some easy targets and missed other completely.

By the end of the round, I was talking to myself. I’m a decent clays shooter, but missed some easy shots while powdering other targets that came out of the same trap. The mystery was solved when I finally shot the over-under at some pattern paper. The upper barrel placed the center of its shot spread about 2 feet high at 25 yards because of a defective choke tube! The other tubes shot right where the gun pointed, explaining why I hit some easy targets and missed other completely.

The obvious solution is to pattern your shotgun, firing several shots with every tube, with a variety of ammunition.

Most of us are better off with wider patterns, making hitting easier. Cheaper lead-shot ammo tends to open patterns somewhat. Even then, the supposed improved-cylinder tube may shoot pretty tightly. The best solution is to order an even more open tube. I generally get mine from Briley Manufacturing Inc., (713) 932-6995, www.briley.com. These will generally be designated skeet or cylinder.

The other trouble with choke tubes is that they sometimes get stuck, and after hunting in really wet conditions they can really get stuck. Cleaning the threads and applying a little lubrication before screwing in a choke prevents these problems, but if a tube still gets stuck, some Kroil penetrating oil applied to the choke/barrel joint and left to soak overnight will often loosen it.

The main thing, though, is to know exactly how your choke tubes act with different kinds of ammo, whether lead-shot or some variety of nontoxic shot. And the only way to learn is to shoot some patterns. The reason most hunters don’t is that the standard method of patterning (invented by those stodgy Brits) is incredibly slow and boring, especially counting all the little holes.

You don’t need to do that. If your local range doesn’t have a pattern board (and most don’t), buy a roll of freezer paper and masking tape, and find a big cardboard box. Most grocery-store freezer paper is 18 inches wide, so tape two pieces side by side.

They can even overlap the sides of the box. Then shoot various kinds of ammo at different ranges, observing the width of the pattern spread and the evenness of the holes. A spread of at least 24 inches for the main part of the pattern makes hitting a lot easier. And 30 inches is better yet if the pattern lands where the shotgun points.

In reality, most of us don’t often shoot upland birds at 40 yards. Most are taken at 20 to 30 yards and even closer in thicker cover.

For some reason, wingshooters have always been obsessed with long shots, but even then, a wider spread helps.

Normally, the birds we take at longer ranges are bigger, such as geese. And a super-tight pattern isn’t required to put several shot into a 10-pound Canada.

Once you know how each of your choke tubes behaves, you will be able to screw in the best one for the conditions instead of just guessing.

This article was published in the November 2009 edition of Buckmasters GunHunter Magazine. Subscribe today to have GunHunter delivered to your home.