Bullet placement is far more important in the field than bullet theory.

Photo: Although black bears are usually not as large as grizzlies, they can be just as dangerous, so it’s best to knock them down. The author prefers a deep-penetrating bullet that will exit, leaving two holes for trailing.

There’s an old joke about the hunter who keeps missing a grizzly bear with increasingly larger and more powerful magnums. Each time he misses, the bear destroys his rifle and abuses him in a degrading way. The punch line has the bear asking the failed, masochistic hunter, “You really don’t come out here for the hunting, do you?”

The joke illustrates an overlooked truism in hunting rifles: No amount of knockdown power compensates for poor shooting.

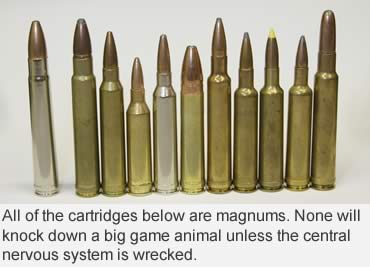

Actually, no amount of knockdown power actually knocks anything down.

You’d be hard-pressed to believe this after reading hunting and shooting articles and advertisements. KNOCKDOWN POWER has been a headline staple since the invention of blackpowder. Heck, it was probably discussed over mastodon steaks around Pleistocene campfires. “Me want bigger spear, more weight in shaft to knock mastodon down!”

You’d be hard-pressed to believe this after reading hunting and shooting articles and advertisements. KNOCKDOWN POWER has been a headline staple since the invention of blackpowder. Heck, it was probably discussed over mastodon steaks around Pleistocene campfires. “Me want bigger spear, more weight in shaft to knock mastodon down!”

“Grog, you first need bigger muscle in arm to throw spear! Har, har, har!”

Unfortunately, physics has a way of throwing a wet blanket over our desires. The truth is neither spear nor bullet energy works the way we think.

Let’s jump right to the heart of the matter with a quick reflection on bow hunting. Even if you’ve never taken a deer with a bow, you’ve probably seen it done. Usually the arrow strikes, the deer leaps in alarm and runs off before succumbing to blood loss. Sometimes, though, the animal drops in its tracks, thrashes spasmodically for a few seconds, and then expires.

What’s going on? Was that “deer hit with a more powerful arrow? Did it collapse as a result of more knockdown power?

No. It was hit in the spine.

No. It was hit in the spine.

This same thing happens with bullets and rifles. Shoot a bullet through the chest of a deer and it will likely run 20 to 100 yards before getting woozy, staggering and falling. Hit it in the spine forward of the shoulders and it will fall in its tracks.

It doesn’t matter if the bullet generates 400 or 4,000 foot-pounds of energy. We’re seeing the effects of bullet placement and tissue destruction rather than knockdown power. Bullets from common shoulder-fired rifles just don’t work the way those energy numbers suggest.

Veteran hunters who’ve taken a variety of game with different cartridges and bullets have come to understand this. There’s just no consistency in knockdown performance. One day a chest shot from a 6mm Remington will kill a whitetail stone dead. The next day, a puny coyote will run 40 yards after hit in the chest shot with a .300 Weatherby Magnum bullet. Some hunters haven’t had the opportunity to observe this. Thus, the myth of knockdown power persists.

Each year, gun sellers are asked which cartridges and/or bullets provide the knockdown power needed to anchor bucks and bulls in their tracks. Neither bullets nor energy work like a head blow from a heavyweight boxer.

If you’ve studied the numbers in trajectory tables, you’re familiar with kinetic energy expressed in foot-pounds. Kinetic energy is energy in motion. A 150-grain bullet standing still has potential energy. Dropped, it has a bit of kinetic energy, and you’ll feel this should it land on your naked toe. Push this same bullet with about 50 grains of Hodgdon 4350 powder behind it, and you won’t want to feel it on your toe or anyplace else. It will be hauling about 3,000 foot-pounds of kinetic energy.

If you’ve studied the numbers in trajectory tables, you’re familiar with kinetic energy expressed in foot-pounds. Kinetic energy is energy in motion. A 150-grain bullet standing still has potential energy. Dropped, it has a bit of kinetic energy, and you’ll feel this should it land on your naked toe. Push this same bullet with about 50 grains of Hodgdon 4350 powder behind it, and you won’t want to feel it on your toe or anyplace else. It will be hauling about 3,000 foot-pounds of kinetic energy.

A foot-pound of energy is sufficient to lift 1 pound 1 foot into the air, so 3,000 foot-pounds ought to lift a 200-pound whitetail 15 feet straight up or at least knock it 10 feet backward (allow for a bit of ground friction to retard the momentum.)

Hunters have told me they’ve seen this. One guy insisted his 7mm Remington Magnum had knocked a bull elk back 10 feet. You can prove him wrong by laying a 50-pound bag of sand on a smooth board and shooting it with your own 7mm Rem Mag. I’ll bet you dollars to donuts it will not be pushed back so much as 5 feet. Not even the .470 Nitro Express shoving a 500-grain bullet from a muzzle at 2,100 foot-pounds and churning up 4,897 foot-pounds of energy will send that 50-pound bag flying.

Consider this energy business from another angle. Two 200-pound football players running into one another at 12 miles per hour generate about 1,925 foot-pounds kinetic energy. Unless one or both sustain a weird head injury, they pick themselves up and line up for the next play. This should strike “knockdown energy” advocates as most strange because those footballers are impacting with roughly the same foot-pounds of energy as a 100-grain bullet shot from a .243 Win. The knockdown power doesn’t kill them, but I’m guessing they wouldn’t want to absorb that bullet.

Bullets kill by wrecking the central nervous system — essentially pulling the electrical plug — and by starving the brain of oxygen by interrupting the cardiovascular system’s ability to pump fresh blood. So, again, a bullet to the brain or neck vertebrae creates a magnificent knockdown effect. The interesting thing is that this effect can come from a 40-grain .22 Long Rifle just as dramatically as from a 400-grain .416 Remington Magnum. And those same bullets to the heart/lungs lead to gradual loss of oxygenated blood flow to the brain, the demise of brain cells, unconsciousness and death.

Bullets kill by wrecking the central nervous system — essentially pulling the electrical plug — and by starving the brain of oxygen by interrupting the cardiovascular system’s ability to pump fresh blood. So, again, a bullet to the brain or neck vertebrae creates a magnificent knockdown effect. The interesting thing is that this effect can come from a 40-grain .22 Long Rifle just as dramatically as from a 400-grain .416 Remington Magnum. And those same bullets to the heart/lungs lead to gradual loss of oxygenated blood flow to the brain, the demise of brain cells, unconsciousness and death.

Famous hunting writers like Robert Ruark and Elmer Keith, mid-20th century proponents of big guns with an overabundance of knockdown power, advocated big bullets atop big cartridges. But both failed to elaborate on how bullets kill and how bullet construction, more than energy, impacts game.

It is true that big, heavy, slow- moving bullets kill quite effectively. It’s also true that small, light, hypervelocity bullets sometimes fail to kill quickly.

But so is the reverse. Plenty of animals large and small have dropped in their tracks when struck by one of Roy Weatherby’s hyper-velocity, small-caliber bullets But not always. What is this phenomenon?

I call it luck. If you’re fortunate, the explosive energy delivered by a hyper-velocity bullet somehow shocks the animal’s system sufficiently to knock it unconscious, after which it expires from oxygen deprivation to the brain.

Just why one heart-shot critter collapses while another runs for all its worth before falling is a mystery. I’ve seen it happen both ways.

Just why one heart-shot critter collapses while another runs for all its worth before falling is a mystery. I’ve seen it happen both ways.

Some say if the bullet strikes at the instant the heart is pumping and blood pressure is at its highest, the shock is more efficiently carried through the animal’s system, including the brain. Problem is, no one has had monitoring equipment on any of these animals at the time of the hit. And no one can predict when any animal’s blood pressure will have peaked in order to time their shot.

I’ve also seen big, heavy, slow-moving bullets punch through the chest of small deer without inspiring the anticipated result. Instead of crumpling on the spot, the little deer ran off as if struck with little more than an arrow.

With its cardiovascular system seriously malfunctioning due to the tissue destruction wrought by the passage of a 300-grain, .50-caliber slug, the deer’s brain cells became oxygen starved. The deer died.

But what about KOV, Taylor Knock Out values? Big-bore advocates often reference this formula. It was invented by John Pondoro Taylor, an ivory hunter.

His formula is supposed to indicate how much bullet weight/caliber/velocity and thus energy is required to knock an elephant silly, if not out, if the brain is missed by an inch or two. This gives the hunter a few minutes to administer the coup de grâce before the pachyderm regains consciousness and wanders off. While this formula might have worked on elephants head shot with solid bullet, it hardly applies to elk shot in the chest with expanding bullets.

There are other well meaning but goofy formulas. The dwell theory suggests the longer a bullet remains or dwells in an animal, the more damage it does. (A bullet that stops halfway through a deer’s chest must really do the job since it dwells there until it is cut out.)

So what does all this mean for the big game hunter? Is a .223 Remington adequate for hunting whitetails? Do we really need a .375 H&H Magnum for moose or grizzly bears? Elmer Keith claimed the .270 Winchester might be an adequate little coyote round, yet hunters have taken everything from elk to brown bears with the .270. What’s the real story?

Bullets. Yup. Bullets are the real story because they do the work of breaking down vital tissue to deprive the prey animal of brain cell oxygen. The more efficiently this is done, the better. It can be done with big bullets moving slowly, small bullets moving fast and sometimes vice-versa. Here’s how it works:

When a bullet strikes game, it begins to expand, much as it would if you sandwiched it between the top of an anvil and a hammer. The more energy you apply with the hammer (weight and velocity), the flatter the bullet is rendered. But in game, a bullet is also moving, so friction plays a role. The wider the bullet expands, increasing surface area, the less it penetrates. A soft bullet that pancakes might penetrate just one lung. It might stop against the shoulder. It will certainly impart all of its energy to the animal, but probably won’t kill it because, as suggested by our colliding football player analogy, living things have a way of absorbing and shaking off mere energy.

When a bullet strikes game, it begins to expand, much as it would if you sandwiched it between the top of an anvil and a hammer. The more energy you apply with the hammer (weight and velocity), the flatter the bullet is rendered. But in game, a bullet is also moving, so friction plays a role. The wider the bullet expands, increasing surface area, the less it penetrates. A soft bullet that pancakes might penetrate just one lung. It might stop against the shoulder. It will certainly impart all of its energy to the animal, but probably won’t kill it because, as suggested by our colliding football player analogy, living things have a way of absorbing and shaking off mere energy.

A better bullet is one that expands to at least twice its normal diameter, and retains enough mass behind the mushroomed nose to continue forward. As it penetrates, it breaks, mashes and cuts tissue it touches, but it also causes pressure damage beyond what it touches. Herein lies the value of high-velocity “shock.”

Much of the shockwave energy can be absorbed by tough, flexible tissues, but fragile tissues tear, decreasing the cardiopulmonary system’s ability to pump oxygenated blood to the brain.

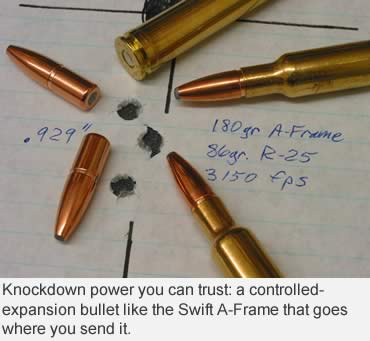

Because the bullet is also spinning on its axis, it can contribute tissue destruction radially. Many pooh pooh this idea, noting that the split second a bullet is in an animal, rotations tare few. Nonetheless, bullets like the Barnes X, Nosler E-Tip, Federal Trophy Bonded and Swift A-Frame that expand into petals show a distinct bend in those petals opposite the bullet’s rotation. This suggests those petals are throwing radial energy if not secondary projectiles like bone fragments.

A bullet that passes completely through increases tissue damage and leaves an opening for blood trailing. A frangible bullet that “explodes” inside the lungs can do incredible radial damage without passing through, but it could just as easily break up on a shoulder.

The ideal, regardless of caliber and velocity, is a controlled-expansion bullet that balances expansion and penetration to maximize tissue destruction. With such a bullet working for you, knockdown power becomes as irrelevant as it always has been.

A well-placed 60-grain bullet from a .223 Rem can terminate a pronghorn or even an elk. A 200-grain bullet from a .300 magnum can do it better, but only if it’s well placed. That’s why smart outfitters recommend their hunters bring a rifle/caliber they can shoot well.

You can hope your game dies in its tracks, but expect it to run until oxygen depletion ends brain function. Bullet placement and bullet performance beat knockdown power every time.

Read Recent GunHunter Articles:

• The Amazing .375 H&H Family: Dozens of rounds have been carved from H&H’s magnum opus.

• Six Rules of Glassing: Good glass and proper technique are the keys to locating game.

This article was first printed in the September 2011 edition of Buckmasters GunHunter Magazine. Subscribe today to have GunHunter delivered to your home.