Dozens of rounds have been carved from H&H’s magnum opus.

Photo: The .375 H&H and its .300 H&H offspring (far left) were too long to function well in standard-length action. Brass was shortened to make the .264 Win Mag, 7mm Rem Mag, .300 Win Mag, .350 Norma Mag and .458 Win Mag.

No centerfire rifle cartridge has spawned a larger extended family than Holland and Holland’s 1912 introduction, the .375 H&H Magnum.

Contrary to popular thought, this was not the first magnum cartridge, nor even the first to wear a belt, which plays no role in making the magnum case stronger.

Yeah, it’s rather confusing.

Magnum is Latin for great. An artist’s greatest work is his magnum opus. In the 1700s, wine merchants began selling two-quart bottles as “magnums.” The first rifle cartridge to be labeled a magnum did not hold two quarts of powder. It was the British made .500/.450 3 1/4-inch Magnum Express unleashed sometime in the 1870s.

In 1909, Westley Richards came out with its .425 Westley Richards Magnum. Neither had a belt. But Holland & Holland’s .400/.375 Belted Nitro Express in 1905 did. It, however, was not called a magnum.

In 1909, Westley Richards came out with its .425 Westley Richards Magnum. Neither had a belt. But Holland & Holland’s .400/.375 Belted Nitro Express in 1905 did. It, however, was not called a magnum.

Few shooters know that the original .375 H&H Magnum was offered with a belt and without. The beltless Flanged Magnum was designed to function in break-action single and double barrels where the flange, the same as a rim on American cases like the .30-30 Winchester, was used for positive headspacing.

Because flanged cartridges didn’t flow smoothly through Mauser-style, stacked-magazine bolt actions, the rim was removed and that famous belt was added for positive headspacing.

Some claim the .375 H&H was originally called the Belted Rimless Nitro-Express in England. Winchester called it the Magnum over here, and that title has stuck.

It arose as an effective medium- to large-game cartridge for buffalo, lion and tiger. This step down in bore size from older rounds was made possible by the increased energies and low carbon fouling of the new smokeless powders.

Not every hunter needed a dangerous-game rifle, but H&H needed more sales, so it reduced the neck of the .375 to make the world’s second belted magnum cartridge. And if you think you know it, hang on. It was not the .300 H&H Magnum, but the .275 H&H Magnum of 1912. This was essentially the equivalent of today’s 7mm Remington Magnum or 7mm Weatherby Magnum, but powders of the day couldn’t push the rounds to their true potential.

Next, in the early 1920s, came the H&H .240 Magnum Rimless, the .243 Winchester of its day. It shoved a 100-grain bullet 2,900 fps.

Next, in the early 1920s, came the H&H .240 Magnum Rimless, the .243 Winchester of its day. It shoved a 100-grain bullet 2,900 fps.

The .300 version, initially labeled the Super Thirty, didn’t debut until 1925. It bettered the popular .30-06 Springfield by about 150 fps. Holland and Holland went on to make a .400 H&H Magnum, .465 H&H Magnum and, in 1955, another 6mm, the .244 Magnum, which took advantage of newer American powders to wring an advertised 3,500 fps from a 100-grain bullet.

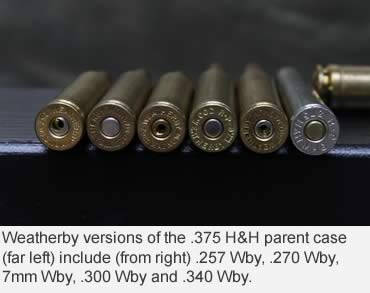

While these proper British developments are interesting, American versions of the .375 H&H mother case are more familiar. Roy Weatherby got the magnum ball rolling in 1943 with a whole series of magnums based on the old H&H case. The first was the iconic .270 Weatherby Magnum. It beat the old .270 Winchester by about 200 fps. To make this and his .257 and 7mm versions, Roy shortened the original .300 H&H case from 2.850 inches to 2.549 inches, minimized wall taper and pushed forward a “double radius” shoulder.

For his .300 version, Roy maintained the full .300 H&H length. The .340 Wby didn’t hit the streets until 1962 after Winchester had proved the value of the .338 caliber with its .338 Win Mag of 1958 based, big surprise, on the H&H case. Each new Weatherby set speed records and helped fix the belted magnum mystique. Only recently was the .300 Wby outclassed by the .300 Dakota, .300 Remington Ultra Mag and .30-378 Wby, all based on fatter cases.

With his improved case shape, Weatherby made the original .375 H&H the .375 Wby in 1945. It was superseded in 1953 by his .378 Wby based on a larger case. In fact, all larger Weatherby calibers are based on this larger case, so we’ll shift to Winchester and Remington for more H&H family developments.

Weatherby’s success inspired Winchester, which announced its .458 Win Mag in 1956. Winchester shortened the .375 case to 2.5 inches so it would more easily fit its Model 70 and Mauser military actions then being converted to sporting use. This attracted customers who couldn’t afford the more expensive Weatherby cartridges.

Weatherby’s success inspired Winchester, which announced its .458 Win Mag in 1956. Winchester shortened the .375 case to 2.5 inches so it would more easily fit its Model 70 and Mauser military actions then being converted to sporting use. This attracted customers who couldn’t afford the more expensive Weatherby cartridges.

Two years later, the .458 WM was necked down to become the .338 WM and .264 WM. The .338 slowly became a respected elk and big bear round. The screaming .264 WM, a direct challenge to the .257 Wby, was labeled the Westerner and took off immediately as a mountain rifle for deer, elk and moose. Remington pulled the rug from under it in 1962 with release of its more efficient 7mm RM, which could handle slightly heavier bullets. Winchester countered with the .300 WM the next year, and the two slugged it out for a couple of decades. They remain two of the most popular magnum rounds in the world, and both owe their success to a parent born 50 years earlier.

Remington got really creative in the mid 1960s by shortening the belted magnum cases to 2.17 inches and chambering them as the 6.5 RM and .350 RM in short-barreled, quick handling carbines that never wrung full potential from the cartridges. After a hiatus, Remington announced one more variation on the .375 H&H theme, its full-length 8mm RM in 1978. While it compares ballistically to the .338 WM, it has never approached its popularity. The 8mm RM was necked down to .284 to become the 7mm Shooting Times Westerner in 1989. It wasn’t recognized as a SAAMI factory round until 1996, at which time it was the fastest commercial 7mm, hitting 3,400 fps with a 140-grain bullet. It was dethroned as Speed King in 2002 by the 7mm RUM.

The obscure 8mm RM has one final claim to fame. Remington necked it up to .416 to make the .416 RM, a challenger to the .458 WM. The .416 RM functions perfectly through the Model 700 long action and, despite its narrower, lighter bullet, retains more energy downrange with a flatter trajectory.

While all this .375 H&H development was churning, the Scandinavians at Norma weren’t asleep at the switch. Seeing a void, in 1959 they raised Winchester’s .338 WM bid with the .358 Norma Magnum. It was created from a shortened .375 H&H case with straighter walls and a sharper shoulder. The case was lengthened to make the .308 Norma Mag in 1960. The advent of the .300 WM just three years later pretty much doomed the Norma version.

Norma in 1953 was the first to produce factory ammunition for the American wildcat 7x61mm Sharpe & Hart, yet another modification of the basic H&H belted case. The S&H is just slightly shorter than the 7mm RM, which put it to pasture. Who knows, if any American gun maker had chambered the S&H in mass-produced rifles, the Remington version might never have been born.

Dozens more wildcats have been carved from the .375 H&H, making it the hands-down champ for inspiring new cartridges. Meanwhile the original remains the most popular .375 caliber in the world — not a bad history.

Read Recent GunHunter Articles:

• Six Rules of Glassing: Good glass and proper technique are the keys to locating game.

• The Perfect Rifle: Planning for the next hunting gun never gets old.

This article was first printed in the September 2011 edition of Buckmasters GunHunter Magazine. Subscribe today to have GunHunter delivered to your home.