The .257 Weatherby is a good alternative to the hard-thumping .30-cal. magnums.

Photo: Long, sleek bullets are pushed to top velocities by the .257 Weatherby Magnum, making it effective for everything from varmints to moose.

It’s often said but seldom appreciated that quarter bores are America’s finest deer cartridges. And the finest of them all is the .257 Weatherby Magnum.

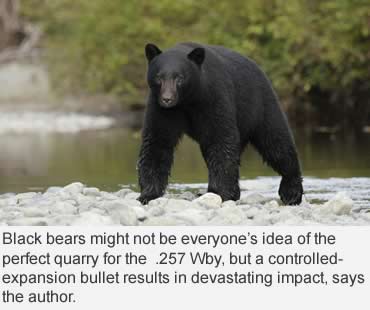

This opinion runs smack against our love affair with .30 bores. But .308 bullets are bigger than needed for whitetails, mule deer, blacktails, sheep, pronghorns, javelina, feral hogs and even black bears. If a .257 bullet does the job, why hire a .308?

That was my thinking when I was offered the use of any Weatherby rifle topped with a Zeiss scope on a Wyoming antelope hunt last year.

“I’ll take a .257, please.” I think I said please. I hope I said it.

At any rate, Brad Ruddell of Weatherby handed me two boxes of Weatherby ammunition and a Mark V rifle. It wore a Zeiss Diavari Victory 4-16x50mm FL scope bright and sharp enough to scout for pebbles on the dark side of the moon.

Deja vu. “Isn’t this the same setup I was shooting in New Mexico the time you rolled that buck running flat out?” I asked Ruddell.

Deja vu. “Isn’t this the same setup I was shooting in New Mexico the time you rolled that buck running flat out?” I asked Ruddell.

“And you dumped the Chernobyl buck on his nose with one shot?” he replied. “Man, that was more than ten years ago. I do remember you were shooting a .257, but I don’t remember what bullets or scopes.”

We’d named my buck Chernobyl because his horn tips appeared to have been melted until they drooped straight down towards his face. When his head poked out of a draw I took a neck shot, confident in the accuracy of the rifle. I wasn’t disappointed. The meat from that instant kill was fantastic.

“Well, hot diggedy dog, the .257 Weatherby rides again,” I crowed. Then I set the Mark V on sandbags to determine which bullet it would like best. Three 110-grain Accubonds clustered under one-half MOA. Three 115-grain Nosler Ballistic Tips held around 3/4 MOA. Subsequent groups told the same tale.

This degree of accuracy from factory ammunition in a factory rifle in a belted magnum case is stunning. I don’t care how often you read about 1/4-MOA rifles, any factory rifle/ammo that shoots sub-MOA is rare. And when it’s a .257 Wby, the combination of accuracy and speed make it flat out deadly. Here’s why:

Stuff 71 grains of IMR 7828 into a .257 Wby case, top it with a 110-grain AccuBond, and it should leave a 26-inch barrel at 3,480 fps, according to the Nosler Reloading Guide #6. Nosler claims a BC of .418 for that bullet. Sight this 2.5 inches high at 100 yards, and it will peak 3.4 inches high at 170 yards, strike dead-on at 300 yards, fall 3.3 inches at 350 yards, 8 inches at 400 yards and 21 inches at 500 yards.

Wind deflection in a 10-mph right angle breeze will be just 6 inches at 300 yards. In short, you can hold dead-on the average mule deer’s chest (17 inches, top to bottom) and land that 110-grain AccuBond in the wheelhouse from spitting distance to 375 yards. No need for a rangefinder, no need for holdover. Only need a skinning knife. Remaining energy at 400 yards should be 1,572 foot-pounds. That bullet isn’t bouncing off any elk.

Wind deflection in a 10-mph right angle breeze will be just 6 inches at 300 yards. In short, you can hold dead-on the average mule deer’s chest (17 inches, top to bottom) and land that 110-grain AccuBond in the wheelhouse from spitting distance to 375 yards. No need for a rangefinder, no need for holdover. Only need a skinning knife. Remaining energy at 400 yards should be 1,572 foot-pounds. That bullet isn’t bouncing off any elk.

Knowing those statistics, and having a Rifles Inc. Lightweight Strata .257 Weatherby in hand while in Mexico a number of years back, I aimed dead-center at a spectacular Coues’ buck at 351 yards measured with a rangefinder. As predicted by the data — and considerable long-range rock powdering I’d done with the rifle earlier — the bullet ended its career with a quick trip through that buck’s spirit room, and down it went.

Roy Weatherby and friends had much the same result on a variety of animals, including several 600- to 700-pound zebras during a 1948 safari in East Africa. Any African PH will tell you zebras of any stripe are heavy, large-boned, tough animals.

They don’t recommend shooting them with “light rifles.” Yet, the .257 Weatherby seems to have handled them quite efficiently, sometimes with little 87-grain bullets.

Roy Weatherby was experimenting with his “hydrostatic shock” theory, trying to determine if a hypersonic bullet that turned to shrapnel inside a beast killed faster than a slow, heavy slug that plowed through.

An honest assessment of his results indicates neither worked unless the bullet was placed in a vital area, but once the vitals were hit, hyper-fast, frangible bullets did often kill quickly.

Sometimes the .257 killed faster than the .375 or even the PH’s .470 N.E. on small antelope as well as large. Weatherby went on to take most Africa and North American game with his .257. It reportedly became his favorite cartridge. It’s becoming one of mine.

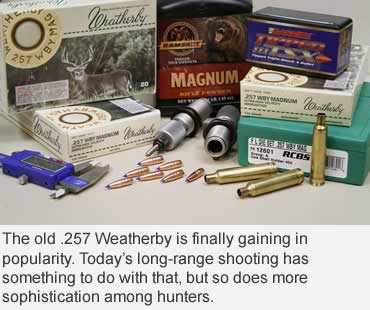

The old .257 Wby is finally gaining in popularity.  Today’s long-range sniping fad has something to do with that, but so does increasing sophistication among hunters/shooters who understand ballistic performance. Folks who tire of the weight of a heavy .300 or .338 or the recoil of a light one start looking for alternatives, and the .257 Wby is a good one.

Today’s long-range sniping fad has something to do with that, but so does increasing sophistication among hunters/shooters who understand ballistic performance. Folks who tire of the weight of a heavy .300 or .338 or the recoil of a light one start looking for alternatives, and the .257 Wby is a good one.

In an 8-pound rifle, the .257 kicking out a 120-grain bullet at 3,200 fps generates 17.7 foot-pounds of recoil energy. The .300 Wby pushing a 180-grain bullet at 3,200 fps generates 30.7 foot-pounds, almost twice as much. Which would you rather shoot?

The mild nature of the .257 Wby helped me collect a rare triple on coyotes in December 2000. I was watching a brushy creek valley from a grassy ridge when two coyotes popped into view about 250 yards away. I couldn’t resist. When the lead dog stopped, bang! Down he went. A minute later, his partner popped back out of the brush to see what had happened and bang! Down he went. About 30 minutes later, a third coyote loped off the opposite ridge, stopped when he stumbled upon his two dead competitors. He joined them on their one-way trip to the fur salon.

Today’s shooter/hunter bias for .308 magnums is somewhat puzzling given our past. Bores measuring .25 inch began making their mark before the .308s. Way back in 1882, the .25-20 single-shot cartridge came on the scene. The only .308 around at that time was the little-used .30-30 Wesson, probably an 1880 invention and no relation to the .30-30 Winchester.

The .30-40 Krag, our first small-bore military cartridge, didn’t make the scene until 1892. Our first truly popular .308 hunting cartridge was the .30-30 Winchester of 1894. But in that era it was competing against the .25-20 Marlin, .25-21 Stevens, .25-25 Stevens, .25-20 and .25-35 Winchesters and .25-36 Marlin.

As our official military cartridge, the .30-06 was bound to be a success, but early users considered it excessive for varmints and even a bit too much for deer. The .250-3000 Savage in 1915 was more eagerly embraced as a deer round. Many folks chambered rifles for Ned Roberts’ .25 wildcat. Remington legitimized it in 1934 as the .257 Roberts. The .30-06 itself was necked down to a .25 wildcat in 1920.

Remington released it 49 years later as the .25-06 Remington. It’s considered a really fast, flat shooter, yet it’s about 200 fps slower and a quarter century older than the .257 Wby.

The most common complaint against the .257 Wby is “overbore,” usually spoken as if one were referencing the drug-addled son of a major Hollywood star. “Sure, the .257 Weatherby shoots fast and flat and hard, but it’s overbored. It burns so much powder.”

The most common complaint against the .257 Wby is “overbore,” usually spoken as if one were referencing the drug-addled son of a major Hollywood star. “Sure, the .257 Weatherby shoots fast and flat and hard, but it’s overbored. It burns so much powder.”

So? Overbored is overstated. So what if you throw 10 grains more powder into a .257 Wby than a .25-06 Rem to gain 200 fps? You shovel 20 grains more into a .30-06 than a .30-30. The .300 Win Mag. gulps 16 grains more Hybrid 100V than the .30-06. And the .300 Rem Ultra Mag. burns 15 grains more Magpro than the .300 Win Mag.

Burning more powder is how you get to be the high-speed champ. What matters is that the .257 Wby does this without giving you a concussion. This, coupled with accurate bullets, barrels and rifles, makes the .257 Wby King of the .25 bores and the perfect choice for long-range hunting of deer-sized game.

Recently I fired a 100-grain Barnes TTSX from a .257 Wby at a black bear. Outfitter Darren Deluca feared it was insufficient. He likes a .30-06 as minimum for Vancouver Island bears. Nonetheless, the little .257 bullet plowed through a 3-inch alder limb, then the bruin’s shoulders. The bear, the single-shot Merkel rifle and I posed for a group photo.

During last year’s Wyoming antelope hunt the .257 Wby Mark V and Zeiss scope proved so accurate that I elected to try a neck shot when guide Casey Tillard directed me toward a cull buck. I try neck shots only with super-accurate rifles when I want the highest quality meat.

According to the Zeiss 8x45 rangefinder binocular, the buck stood 180 yards away. I was zeroed 3 inches high at 100 yards, so I held 4 inches low. The wind speed suggested allowing for 9 inches of drift. Casey and I agreed on this, so that’s how we aimed. The buck collapsed in a heap. The meat was delectable, surpassing the elk already in the freezer.

The .257 Wby was ahead of its time in 1945, but shooters who don’t recognize its prowess today are behind the times. This little hot rod shows what a super quarter bore can do. Which is just about everything. Especially with today’s powders, bullets, scopes, rangefinders and rifles. Get yourself a .257 Weatherby and you’ll see.

Read Recent GunHunter Articles:

• A Wild Hog Sledgehammer: The stout .45-70 cartridge is bad medicine for big pigs.

• Coming Clean: Gun cleaning considerations and tricks beyond the norm.

This article was first printed in the October 2011 edition of Buckmasters GunHunter Magazine. Subscribe today to have GunHunter delivered to your home.