Many variables can affect velocity readings. Here’s how to set up for best results.

Photo: Setting up a chronograph so bullets pass straight and about 6 inches over the top of the photo sensors helps produce precise readings.

A chronograph reveals a lot about rifle and pistol cartridges, from velocity to consistency. But how do you know whether the chronograph’s readings are correct? Really you don’t, because once a cartridge is fired, it can never be exactly recreated. So you have to have faith the chronograph is calibrated correctly and understand how external forces can influence readings.

Most chronographs have two photo sensors. As a bullet passes over the first one, it detects the bullet’s shadow and trips a counter. When the shadow crosses the second sensor, the counter shuts off. The chronograph converts this interval of time into feet per second.

By keeping the chronograph turned on and firing additional shots, it determines high, low and average velocities, extreme spread and standard deviation. The lower the standard deviation — a complex measurement of variation — the more uniform the velocity and thus more accurate the load.

Chronograph Position

Chronograph Position

Providing those sensors with an unobstructed view of a bullet’s shadow is the first step in recording correct readings. One summer afternoon, I was shooting a .220 Swift over my Shooting Chrony Beta Master chronograph. The Swift was producing blazing velocities, so I knew something was haywire when the Chrony went from registering 3,800 fps to 700-900 fps.

As I sat there scratching my head, the Chrony started spitting out all sorts of strange numbers. Then I noticed clouds racing overhead.

To deal with the changing light, I installed a white plastic diffuser above each sensor. The readings returned to normal.

Another time, I was recording the velocities of .257 Weatherby loads. Readings indicated the chronograph was possessed by demons.

A cartridge that shoots bullets out of a quarter-inch hole at magnum velocities produces tremendous muzzle blast. Figuring those blasts had created a false shadow over the sensors 9 feet from the muzzle, I moved the chronograph out to 15 feet. The Chrony stopped spitting out weird numbers.

Sometimes, though, a chronograph registers an abnormal velocity for no reason. I just push the forget button and chalk it up as a quirk. But something is wrong if those numbers persist.

I was shooting Berger 87-grain target bullets with three different powders from the .257 Weatherby. Velocities were between 3,100 and 3,200 fps, at least 200 fps slower than they should have been.

I loaded the Bergers again, and the average velocity dropped even more. All I could figure was those long, shiny bullets didn’t provide enough shadow for the photo sensors to detect.

I colored the bullets with a Magic Marker, and velocities jumped up to slightly over 3,400 fps, about where they should have been.

To determine how the position of a chronograph can affect readings, I conducted an experiment. I placed the chronograph exactly 9 feet from the rifle’s muzzle and leveled both sensors.

With a Remington Model 700 SPS .223 shooting 26.8 grains of Ramshot TAC powder and a Nosler 50-grain Ballistic Tip bullet, the load had an average velocity of 3,368 fps and a standard deviation of 13. Tilting the chronograph forward so the sensors were uneven by a couple of inches decreased the average velocity to 3,278 fps and increased standard deviation to 64. Tilting the sensors to the side resulted in an average velocity of 3,250 fps and a standard deviation of a whopping 246.

Other Factors That Affect Readings

Other Factors That Affect Readings

Powders unaffected by temperature changes supposedly provide more consistent velocities. But a temperature difference of 30 degrees can affect primer flame intensity, the brass case and the gun itself and, ultimately, bullet speed.

Ramshot TAC is one of these temperature-insensitive propellants. When I conducted the chronograph positioning experiment, the temperature was 75 degrees and the velocity of Nosler 50-grain Ballistic Tips was 3,368 fps. Shooting other .223s from the same box of cartridges on other days at different temperatures resulted in the following average velocities: 65 degrees, 3,358 fps; 30 degrees, 3,280 fps; 28 degrees, 3,281 fps.

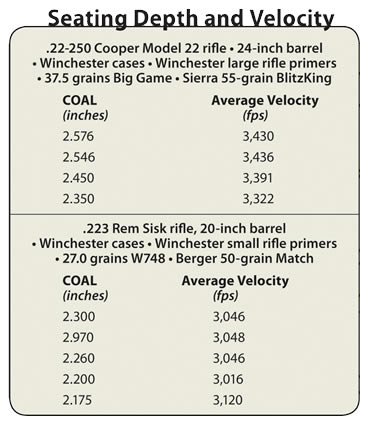

Even a seemingly insignificant change in bullet seating depth can affect velocity. I recorded the average velocity of some .22-250 and .223 Remington loads, with seating depth the only change.

The average velocity of the .22-250 decreased as bullet seating depth increased. That’s because a .22-250 case has more than enough internal capacity to hold 37.5 grains of Ramshot Big Game powder. With some room left over, deeply seated 55-grain bullets do not encroach on the powder space.

The deeper bullets are seated, the greater the pressure and velocity reduction, because the bullets have an increasingly unhindered running start before they contact the rifling.

Velocity of the 50-grain Berger bullets fired from the .223 Sisk rifle remained fairly constant. Cartridge overall length (COAL) was 2.300 to 2.260 inches.

Velocity dropped a bit with a 2.200-inch COAL. However, velocity spiked with a COAL of 2.175 inches. The 27.0 grains of W748 powder pretty well filled the case. Bullets seated that deep intruded on the powder space enough to raise pressure to jump bullet velocity a good 100 fps.

Velocity dropped a bit with a 2.200-inch COAL. However, velocity spiked with a COAL of 2.175 inches. The 27.0 grains of W748 powder pretty well filled the case. Bullets seated that deep intruded on the powder space enough to raise pressure to jump bullet velocity a good 100 fps.

Various handloading manuals show a velocity of about 3,250 to 3,300 fps with a 50-grain bullet and the same powder weight. Those velocities were with 24-inch barrels. Velocity with the 20-inch barrel of the .223 rifle is about 100 fps slower.

Variations in bore diameter, rifling groove depth and smoothness, chamber dimensions, throat shape and headspace can also affect velocity.

All these variables affect chronograph readings. But if you can eliminate or at least mitigate them and set up a chronograph the same way every time, you can have faith the numbers it displays are correct.

Read Recent GunHunter Articles:

• Legacy of the ’98 Mauser: Can you think of any 19th century product still being made and used today? Such is the genius of Peter Paul Mauser’s M98.

• Return of the Bolt-Action Slug Gun: Turnbolt shotguns are the hottest tickets in slug gun shooting today.

This article was first printed in the September 2011 edition of Buckmasters GunHunter Magazine. Subscribe today to have GunHunter delivered to your home.