By Jon R. Sundra

Factors to consider when buying or rebarreling a hunting gun.

Photo: H-S Precision is one of a handful of makers using the traditional hook method of rifling. The process can be done after the barrel is contoured, and it need not be stress relieved afterward.

There are many ways to make a rifle more accurate. Bolt lugs can be lapped to evenly distribute thrust forces. Bolt faces can be squared with the bore.

You can install a match-grade trigger, bed the barreled action and ensure the recoil lug is bearing evenly. All contribute to accuracy, but without a good barrel, they’re pretty much meaningless.

The action may be the heart of a rifle, but the barrel is its soul.

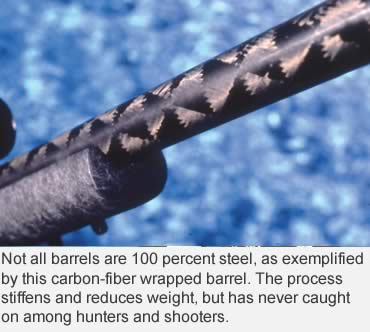

Any discussion of rifle barrels begins with the steel. Until fairly recently, chrome-moly alloys were the standard. About 40 years ago, stainless alloys were developed but did not come into general use until about a quarter-century later. The quality standards for barrel steel of either type are very stringent, and only a handful of companies worldwide are capable of supplying it.

There are four basic ways to rifle a gun barrel: 1) the hook method, in which grooves are cut one at a time with multiple passes of a single cutting tool; 2) broaching, which cuts all the grooves with one pass of the tool; 3) hammer forging, which both shapes and rifles the barrel (and sometimes chambers it as well), all in a single operation; and 4) buttoning, a process in which grooves are actually ironed into the bore.

There are four basic ways to rifle a gun barrel: 1) the hook method, in which grooves are cut one at a time with multiple passes of a single cutting tool; 2) broaching, which cuts all the grooves with one pass of the tool; 3) hammer forging, which both shapes and rifles the barrel (and sometimes chambers it as well), all in a single operation; and 4) buttoning, a process in which grooves are actually ironed into the bore.

The type of steel selected depends to some extent on the rifling process to be used. The alloys best suited to cut rifling are different from those for buttoning or hammer forging.

Although touted as stainless, the type of steel in gun barrels is merely rust-resistant. Stainless usually has a longer accuracy life, but that’s not a given because of the many variables involved. Generally, stainless lasts longer and for that reason is widely favored by competitive shooters.

Stainless cannot be blued using traditional methods, so most manufacturers just bead-blast it, which results in a gray matte finish. There are various proprietary coatings that can be applied to stainless to blacken it and provide an extra measure of durability. Teflon, Armoloy, electroless nickel and TriNyte are just few.

The first step in making a barrel after the steel bars are cut to length is the deep-hole drilling process. You needn’t be a machinist to appreciate how difficult it is to start drilling a hole at one end of a 28-inch steel bar and come out the other end within a few thousands of an inch of center! In fact, if the hole is off much more than that, the blank is scrapped.

The first step in making a barrel after the steel bars are cut to length is the deep-hole drilling process. You needn’t be a machinist to appreciate how difficult it is to start drilling a hole at one end of a 28-inch steel bar and come out the other end within a few thousands of an inch of center! In fact, if the hole is off much more than that, the blank is scrapped.

The bit used for deep-hole drilling looks nothing like a conventional drill. It has only one cutting edge, and there’s a hole through its center to allow a pressurized flow of oil to flush chips out the back.

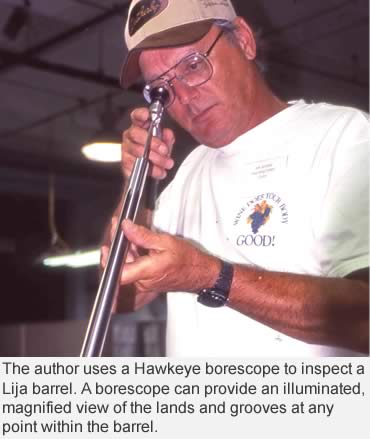

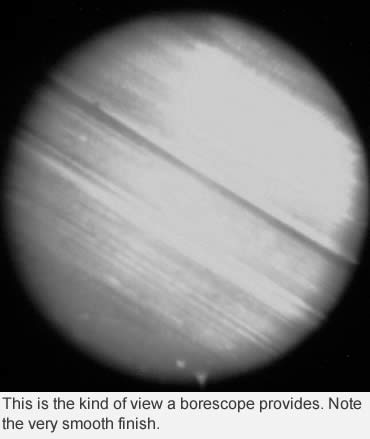

Once the barrel passes muster for concentricity, the next step is reaming the hole, a multi-step operation that is even more important than a centered bore. Reaming is necessary to polish out striations and chatter marks left behind by the deep-hole drilling.

Reaming also brings the bore to its final dimension. Using a .30-caliber barrel as an example, the initial hole will be around .285 inch. Each of two or more reaming stages enlarges and polishes the bore so that when finished, it measures about .300 inch or slightly less. At this point, the bore should have a mirror-like finish.

Both the deep-hole drilling and reaming processes are pretty much the same regardless of the rifling method used. In both operations, the barrel is spun — not the tool bits.

Both the deep-hole drilling and reaming processes are pretty much the same regardless of the rifling method used. In both operations, the barrel is spun — not the tool bits.

To my knowledge, no production rifle manufacturer today uses the broaching method for anything other than pistol barrels. Linear broaches (push/pull) are expensive and somewhat fragile, but when high volume is needed and expense is no object — such as in war production — broaching has been the preferred method.

If you can imagine six linear rows of 10 or more cutting teeth on a drill, with each tooth about .0001 inch higher than the one in front of it, you can visualize what a broach looks like.

Hammer forging is the most common method of rifling a gun barrel today. The process, more accurately called rotary forging or rotary swaging, was developed in Germany in the late 1930s. I believe Sako of Finland was the first to use the process for sporting rifles, starting in the 1950s.

With hammer forging, a button or mandrel similar to those used in button rifling is brazed to the end of a steel rod and inserted into one end of the barrel. The outside (groove) diameter of the button closely matches the inside diameter of the reamed bore. The barrel is then slowly pushed through a set of four powerful hammers oriented on 90-degree centers that literally mash or swage the barrel over the mandrel.

The jaws of the hammer are conceptually similar to a lathe chuck, but instead of locking around a cylinder, the jaws reciprocate radially and hammer the barrel with as much as 100,000 psi. Both forge and mandrel remain stationary; only the barrel moves through the hammer jaws.

The jaws of the hammer are conceptually similar to a lathe chuck, but instead of locking around a cylinder, the jaws reciprocate radially and hammer the barrel with as much as 100,000 psi. Both forge and mandrel remain stationary; only the barrel moves through the hammer jaws.

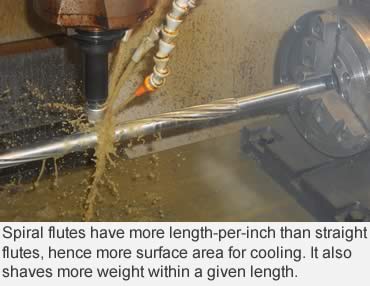

It takes only a couple of minutes to rifle the barrel and shape it to its final contour so that only a minor polishing is needed to finish it.

As mentioned previously, some manufacturers, particularly those with military contracts, also hammer forge the chamber in the same operation. And some European gun companies do not polish the barrel, preferring to leave the small, symmetric facets left by the hammer blows. The result is a very distinctive look to the finished rifle.

Hammer-forging machines are very costly, which is why only major manufacturers use them. The process results in a very smooth internal finish that greatly reduces tooling marks left behind by the drill bit and reamers.

Hammer-forging also lends itself to high-volume production. Its downside is the difficulty of maintaining the same degree of uniformity from chamber to muzzle as with button or hook rifling.

Ruger, Winchester and Sako are just some of the manufacturers that use hammer-forging. All cut the chamber in a separate operation.

The stresses induced by hammer forging are quite severe. A barrel that goes into the machine is only about two-thirds the length of the finished barrel. That’s how much is elongated by this process, which imparts pressure with every blow of its multiple hammers.

The stresses induced by hammer forging are quite severe. A barrel that goes into the machine is only about two-thirds the length of the finished barrel. That’s how much is elongated by this process, which imparts pressure with every blow of its multiple hammers.

If there’s an advantage to hammer forging, it’s that the bar stock needs only be about 16 to 18 inches long. Also, deep-hole drilling is faster and more likely to maintain a high degree of concentricity with this method.

The stress-relieving procedure —heating and slowly cooling the barrel — is a critical step. Without it, a barrel will tend to be erratic and change the point of impact as it heats up from rapid shooting.

Oddly enough, cryogenics is another method used to relieve stress. Instead of heating the rifled barrels to around 1,000 degrees, the cryro process freezes barrels to near absolute zero.

There are proponents of both methods, as both seem to relieve stresses within the steel.

Among most small custom barrel and rifle makers, button rifling is the preferred method. It’s also the most economical one.

As described earlier, button rifling involves pulling a small carbide button through the barrel. Again using a .30-caliber barrel as an example, the reamed barrel will measure .300 inch, give or take a few tenths. The button is slightly larger than the desired final bore/groove dimensions. This is because after the button is forced through the bore to “iron in” the grooves, the metal wants to spring back slightly, just like a cartridge case does after firing. Otherwise, it would be impossible to extract it from the chamber.

Button rifling requires a blank of uniform diameter so resistance to the button is likewise uniform over its the entire length.

Button rifling requires a blank of uniform diameter so resistance to the button is likewise uniform over its the entire length.

Only after the steel bar is rifled can it be turned and shaped to final contour. When the barrel is turned down to final contour, there’s a tendency for it to expand or bell slightly at the muzzle end, where so much more material has been removed than in the chamber area. Stress relieving is very important to minimize this effect.

Button rifling is half art, half science, and each barrel maker has his own secrets.

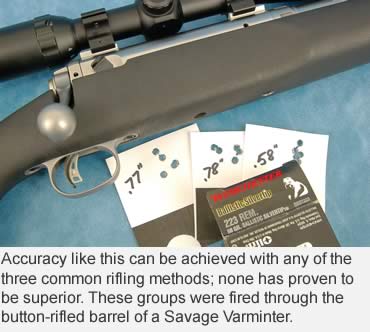

Savage Arms is one major manufacturer that button-rifles its own barrels. Among the better known independent barrel makers are E.R. Shaw, Douglas, Shale, Lilja and Hart.

Lastly, we come to cut rifling, a procedure that can be traced as far back as 1492 to Nuremburg, Germany. The process, however, didn’t come into widespread use until the 19th century.

Even with modern machinery, hook rifling is a tedious, repetitive process that takes about 90 minutes per barrel. A single cutting tool is slowly pulled through the bore, and with each stroke, a wedge pushes the cutting tool outward about a 10,000 of an inch so that each successive stroke deepens the groove by that amount until a depth of about .004 to .006 inch is reached, depending on caliber.

There are definite advantages to cut rifling. No stress is induced, so the barrel can be fully shaped to its final contour before the rifling process. Also, there’s no need to stress-relieve the blanks afterward — a must after button rifling or hammer forging.

Another advantage with cut rifling is that it costs no more to do a twist rate different from whatever the standard happens to be for a given caliber — an important consideration for competitive shooters who want the optimum twist rate for a given bullet rather than a compromise. Standard twist rates must stabilize a wide range of bullet weights.

Another advantage with cut rifling is that it costs no more to do a twist rate different from whatever the standard happens to be for a given caliber — an important consideration for competitive shooters who want the optimum twist rate for a given bullet rather than a compromise. Standard twist rates must stabilize a wide range of bullet weights.

Here, we have barely scratched the surface of what is a very complex subject. Indeed, an entire book can easily be written on the various rifling methods and the pros and cons for each.

As to what conclusions can be drawn, well, it’s safe to say that button-rifled barrels far outnumber cut-rifled barrels in all forms of competitive shooting, but that’s only because cut rifling is more expensive, far more time-consuming, and very few companies are willing and/or capable of doing it. A few that come to mind are H-S Precision, Obermeyer Rifled Barrels, Rocky Mountain Rifle Works and Krieger Barrels.

Hammer forged barrels are very smooth and uniform, but the cost of the machine puts them out of reach of the smaller shops and gunsmithing houses that produce virtually all custom and semi-custom rifles used by hunters and competitive shooters.

Make no mistake, though. All three methods can result in a highly accurate barrel. That’s good to know when a trophy-class pronghorn is in your sights at 400 yards.

Read Recent GunHunter Articles:

• Those Sweet Single Shots: One-shooters don’t have obvious advantages over repeaters, but there are some.

• Predator Calling Setup: Electronic callers make predator hunting easy. Here’s where to set up and what firepower to bring for success.

This article was first printed in the August 2011 edition of Buckmasters GunHunter Magazine. Subscribe today to have GunHunter delivered to your home.