Shop carefully, and you can find an inexpensive scope that hangs with you year in and year out.

When you raise your rifle at sunset and the scope shows a bright orange haze instead of the buck standing at the edge of the timber, the answer to the question “Did I spend enough on my scope?” is no.

The orange haze incident actually happened to my brother, Bob. He had a shiny new .270 Winchester that could outshoot any gun the rest of our little gang owned. But I had a better chance of killing that big whitetail with my open-sighted .30-30 than Bob did with his cheap scope.

Problem was, I was nowhere near that buck. And if Bob had spent another $50 on his scope, that rack would be in his house instead of in his memories.

So how much money did he really save by buying that bargain basement scope?

As hunters, we have things backward. We shouldn’t buy scopes to mount on rifles. We should buy rifles to mount under scopes. Without a good telescopic sight, the world’s most expensive, accurate rifle is as effective as a thrown rock.

As hunters, we have things backward. We shouldn’t buy scopes to mount on rifles. We should buy rifles to mount under scopes. Without a good telescopic sight, the world’s most expensive, accurate rifle is as effective as a thrown rock.

This is why experts tell us to buy as much scope as we can afford and then spend a little bit more.

“All well and good,” you say. “But how am I supposed to know how much to spend to get a good, functional, dependable scope? I can’t slap down $1,500 for a Swarovski Z6 or Zeiss Diavari or even $700 for a Trijicon or Vortex Viper. What can I get for $100?”

Trouble. Scores of game animals have been taken with cheap scopes, but many more escaped.

It’s not that really low-priced scopes don’t work; it’s that they don’t always work. And they never work as well as they should when you really need them, when conditions are less than optimal.

I don’t know about you, but I want my scope, like my rifles and shotguns and handguns and muzzleloaders, to ALWAYS work. That means when the light is dim as well as bright. When the sun shines in my face as well as behind it. When the buck is peeking out of a shadowy draw 10 seconds before the end of legal shooting light. On my 100th shot as well as my first.

We all want a scope to be clear and bright, but we need more than that. Understanding what makes a scope perform properly can help us select one that is adequate without breaking the budget.

Here is my priority list for scope performance:

Here is my priority list for scope performance:

1) Retain zero. We get carried away with optical quality. We don’t need to see a gnat’s eyelashes at 1,000 yards. We just need to see the target, put the reticle on it and have the bullet go where the scope is pointing. If the crosshairs wander or don’t hold zero, the finest optical quality in the world means little.

How do you know a scope will keep its zero? Good question. I’ve seen some dirt- cheap scopes that were still zeroed after 30 years of use.. I’ve seen others that failed after 10 shots, and even some $1,000 scopes that wouldn’t hold zero. They are all mechanical devices subject to breakage and weakening.

You’d think paying more for one would ensure durability and consistency, and you’d be right, but there’s no guarantee. Well, there might be a guarantee to repair or replace, but that’s a small consolation when a nice 10-pointer walks because your scope went out of whack. I’ve suffered that frustration.

2) Provide a clear, sharp image with minimum glare or haze. Here’s where all kinds of optical qualities come into play. And this stuff we can at least see. A scope must resolve targets clearly enough so that we don’t think a stump is a deer or vice versa. We don’t need a scope to resolve as well as a spotting scope, though. A slightly fuzzy target can be okay, so here we can save a few bucks. Generally, even inexpensive scopes have good enough resolution for big game hunting to reasonably long range, say 400 yards.

Low magnifications appear sharper and brighter than high. Magnification enlarges flaws in the lenses. Stay under 10x.

Low magnifications appear sharper and brighter than high. Magnification enlarges flaws in the lenses. Stay under 10x.

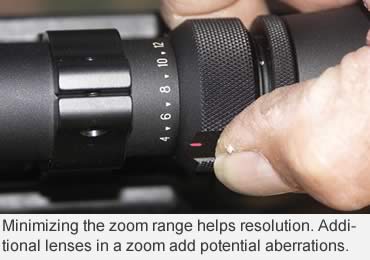

Minimizing the zoom range also helps resolution. Additional lenses are needed in a zoom, and each one adds more potential aberrations. Each lens also soaks up more light, which brings us to a feature you’ll want to spend a few bucks on: anti-reflection lens coatings. Coatings increase brightness and decrease flare, that orange haze my brother saw when he aimed toward the setting sun.

Flare is uncontrolled light created when light bounces off lenses, then ricochets back. With five to nine lenses in a scope, each with two surfaces, those photons are bouncing around in there like pinballs, Mr. Wizard.

Anti-reflection coatings tame them. One layer cuts light reflection loss in half. Multiple layers can knock it to well under 1 percent per lens surface. This adds cost, but no weight and no mechanical complications -— maximum bang for your buck. Make sure your scope has at least one layer of anti-reflection coating on each air-to-glass surface. Most do. Even better is a multi-layer on the objective lens and single layers everywhere else (called multi-coated.) Many $100 to $150 scopes have this. Best is multiple coatings on all lens surfaces, called fully multi-coated. This usually pushes prices over $200.

When light is passed through each lens instead of bounced off, contrast goes up. Contrast means you can see subtle differences between shades of color such as gray bark and twigs and gray deer hide and antlers. So anti-reflection coatings help you see in the shadows, while looking toward the sun, and in low light.

When light is passed through each lens instead of bounced off, contrast goes up. Contrast means you can see subtle differences between shades of color such as gray bark and twigs and gray deer hide and antlers. So anti-reflection coatings help you see in the shadows, while looking toward the sun, and in low light.

The lower the power, the brighter the image, another reason to shy from high magnification. The fewer the lenses, the brighter the image, another reason to get a fixed power. A 4x scope is adequate for deer-sized game to 400 yards. A 6x will suffice for 600 yards.

3) Consistency. Or call this repeatability. It’s a subset of #1 above. Mechanically the instrument should function without changing image quality, field-of-view, focus/sharpness or point of impact (zero). Cutting the cams precisely so the image stays centered on the reticle throughout the zoom range is the trick, and cheaper scopes don’t usually pull it off with precision.

Worse, as the parts wear, precision declines. If you buy an inexpensive zoom, resist the urge to twist the zoom ring unnecessarily. Test accuracy by shooting groups at bottom, middle and top settings to see if and by how much each changes point of impact.

4) Turret accuracy isn’t critical unless you are dialing MOA corrections for windage or drop — not recommended in a low-end scope. If you have a 1/4-inch turret, each click should move point of impact by a quarter inch at 100 yards. Few guns are accurate enough to test this, so try for four clicks, or 1 inch, even eight clicks, which is 2 inches at 100 yards. If your group centers only move half that much or twice that much, you’ll know your turrets don’t adjust precisely. Big deal. Sight in and leave them alone unless your gun starts shooting off.

4) Turret accuracy isn’t critical unless you are dialing MOA corrections for windage or drop — not recommended in a low-end scope. If you have a 1/4-inch turret, each click should move point of impact by a quarter inch at 100 yards. Few guns are accurate enough to test this, so try for four clicks, or 1 inch, even eight clicks, which is 2 inches at 100 yards. If your group centers only move half that much or twice that much, you’ll know your turrets don’t adjust precisely. Big deal. Sight in and leave them alone unless your gun starts shooting off.

To break loose a sticky turret/erector tube correction, note what setting the turret is on, then turn it a complete rotation or more. Tap lightly atop the turrets with a plastic screwdriver handle to jar them slightly. Then rotate back to your starting point. Now dial in the required clicks to zero the gun.

The eyepiece diopter adjustment ring on some scopes may loosen over time. This can cost you a shot if it screws so far in or out while you’re hunting that you can’t clearly see the crosshair. Prevent this by encircling the diopter adjustment collar with a strip of black electrical tape.

4) Waterproof/Dustproof. Virtually every scope made now has this guarantee. Test it by submerging the scope in a sink of tap water as soon as you get it home. You might confirm with the salesclerk that he really will take it back if it’s not waterproof. He might insist you take that up with the manufacturer, instead, so maybe you should call them first and get a verbal confirmation that their written guarantee is good. Then do the dunk.

If you want to be a stickler, take off the turret caps. This really tests things, and is likely to bring a slight leak. After all, there are screws running down through that area, and it’s easy for an o-ring seal to tear, dry out or get torn slightly during assembly. To be fair, test with the turret caps on. After all, are you ever going to hunt with them off?

If you want to be a stickler, take off the turret caps. This really tests things, and is likely to bring a slight leak. After all, there are screws running down through that area, and it’s easy for an o-ring seal to tear, dry out or get torn slightly during assembly. To be fair, test with the turret caps on. After all, are you ever going to hunt with them off?

If water hasn’t seeped inside after an hour, congratulations. You’re good to go.

Really inexpensive scopes are great for guns to be used in good light. Optics aren’t truly tested until the light gets low or shines right onto the objective lens. You could save big bucks on a varmint scope with just single layer coatings and put your savings toward a fully multi-coated scope for low-light deer hunting. Mounting a 3-9x40 or 4-12x42 on any hot .224 or .243 could provide all the performance you’ll need for chucks, prairie dogs, rabbits, small game and coyotes. A straight 4x could team up with a slug gun, muzzleloader or .30-06-class centerfire and give decades of perfect service. Shop carefully, and you could find an inexpensive scope that hangs with you year-in and year-out, amazing you and your friends with its consistent performance.

Read Recent GunHunter Articles:

• Belly Down for Accuracy: Prone isn’t the fastest shooting position – nor is it always practical, but it’s by far the steadiest.

• Whatever Happened to Walnut? Beautiful in color and grain, walnut is the most traditional material for stocking a sporting rifle.

This article was first printed in the August 2011 edition of Buckmasters GunHunter Magazine. Subscribe today to have GunHunter delivered to your home.