By Jon R. Sundra

Beautiful in color and grain, walnut is the most traditional material for stocking a sporting rifle.

Photo: High-grade guns like this Sauer 303 are traditionally stocked in fancy grades of walnut, such as this example of Turkish origin. Walnut cannot be matched for beauty, but there are more efficient stocking mediums.

When I was growing up in the 1950s and ’60s, it was a given that any decent rifle came with a wood stock, and that wood was walnut. There were some entry-level guns — .22 rimfires mostly — that came with hardwood stocks, often sycamore, but any real rifle had a walnut handle. It could be of the plainest, slab-sawed chunk of wood with little or no color or grain structure, but it was walnut. Most new rifles sold today sport stocks that are either synthetic or laminated hardwood.

Walnut has always been considered the most traditional, if not the best, medium for stocking a sporting rifle. It can be breathtakingly beautiful in its color and grain pattern. It’s relatively light in weight, strong and has a compact grain structure that holds checkering and carvings well. When a stock is laid out so that its grain runs roughly parallel to the barrel, it can be relatively stable, provided all surfaces, inside and out, are protected from moisture with a good waterproof finish. In the old days, hand-rubbed linseed or a similar oil finish really brought out whatever color and grain structure was present. Oils are still used by most high-grade custom gun makers. As a protective finish, though, oil leaves a lot to be desired.

Walnut has always been considered the most traditional, if not the best, medium for stocking a sporting rifle. It can be breathtakingly beautiful in its color and grain pattern. It’s relatively light in weight, strong and has a compact grain structure that holds checkering and carvings well. When a stock is laid out so that its grain runs roughly parallel to the barrel, it can be relatively stable, provided all surfaces, inside and out, are protected from moisture with a good waterproof finish. In the old days, hand-rubbed linseed or a similar oil finish really brought out whatever color and grain structure was present. Oils are still used by most high-grade custom gun makers. As a protective finish, though, oil leaves a lot to be desired.

As suitable as walnut is as a stocking medium, it is prone to warping if subjected to prolonged high humidity, drenching rain or melting snow. Warping is the result of the wood either absorbing or expelling moisture, which swells or shrinks the wood, respectively.

Ever see a door that sticks in the summer, but not in the winter? What about a step in the seam between the butt of the stock and recoil pad on a rifle? Depending on the moisture content of the stock and the humidity at the time the two were belt sanded as one piece for a seamless match, prolonged exposure to higher or lower humidity levels will see a step form between the two. That’s because the stock has swollen to where it’s now larger than the inert buttplate or pad. You can see and feel the step with your finger.

Conversely, if the rifle is taken to an arid climate, the wood will shrink so that the step is now formed by the butt being smaller than the pad. Either way, it’s just a few thousands of an inch, but it’s easily seen and felt, and proof positive that wood is not inert.

Conversely, if the rifle is taken to an arid climate, the wood will shrink so that the step is now formed by the butt being smaller than the pad. Either way, it’s just a few thousands of an inch, but it’s easily seen and felt, and proof positive that wood is not inert.

Now imagine if a rifle is tightly bedded in a stock to where the fore-end tip is exerting dampening pressure against the barrel. Unless that pressure always remains constant, that gun will change zero from season to season. Whether the direction of the warp is up or down, side to side, it will change the zero.

With a tightly bedded barrel, you can’t see the warp, but with a floating barrel, you can. I once had a rifle with a barrel smack in the middle of the channel in late summer, with a ⅛-inch gap evenly around its bottom hemisphere. But in the dead of winter when humidity was low, the barrel touched on one side! Imagine the pressure that stock would have exerted on a barrel if it had been tightly bedded at the fore-end tip!

Again, this tendency for a rather slender 30-inch piece of wood to warp can be greatly reduced with a thorough application, inside and out, of finishes like the polyurethanes used on most factory rifles today.

A full or partially floating barrel also contributes to a rifle’s stability, although it may not shoot groups as small as it would with a fully bedded barrel.

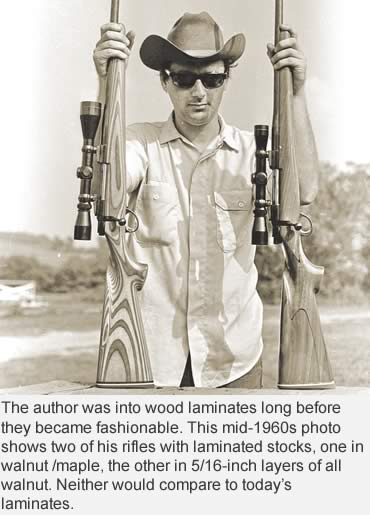

I’ve always felt a rifle is a tool rather than an object of art. Still, I can appreciate a finely crafted walnut stock as much as the next guy. I concluded very early on in my career there were more efficient stocking mediums than walnut, so as early as the mid-’60s I was bedding my rifles in stocks of laminated wood. Unlike today’s broad selection of factory rifles with laminated stocks, in those days you had to go to companies like Herter’s, E.C. Bishop or Reinhart Fajen for semi-inletted laminates. And there was no such thing as firearm-quality laminates; stocks were carved from blanks supplied primarily to companies making furniture.

I’ve always felt a rifle is a tool rather than an object of art. Still, I can appreciate a finely crafted walnut stock as much as the next guy. I concluded very early on in my career there were more efficient stocking mediums than walnut, so as early as the mid-’60s I was bedding my rifles in stocks of laminated wood. Unlike today’s broad selection of factory rifles with laminated stocks, in those days you had to go to companies like Herter’s, E.C. Bishop or Reinhart Fajen for semi-inletted laminates. And there was no such thing as firearm-quality laminates; stocks were carved from blanks supplied primarily to companies making furniture.

It wasn’t until the mid-’80s that Jack Barrett of the Rutland Plywood Corp. came up with a process for making high-quality laminates using white birch veneers just 1/16-inch thick. An average gunstock consisted of about 32 individual layers, each with a different grain orientation than the one beside it. Any tendency to warp is negated as a result.

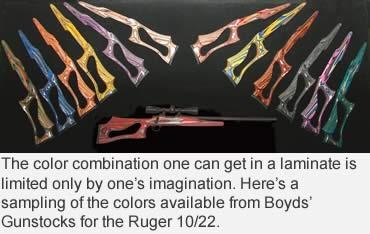

Although it took a few years to really catch on, laminated stocks have become very popular. The availability of many contrasting color combinations and the contour map effect that results from cutting across multiple veneers is attractive to all but the most conservative hunters and shooters.

If laminates are virtually inert, synthetic stocks of fiberglass are literally so. By hand-laying epoxy-laden fiberglass cloths into a mold, pioneers like Chet Brown, Lee Six, Gale McMillan and Tom Houghton fashioned stocks that were dimensionally stable, light and extremely strong. But if truth be told, in those early days they were crude, unattractive and were difficult to inlet and finish.

Like all technologies, however, by the mid-’70s it improved over time. Now, laid-up fiberglass handles can duplicate the lines of the finest wood stocks.

The first production rifles with laid-up fiberglass stocks appeared in mid-’80s. They included Weatherby’s Fibermark and Sako’s Fiberclass, both supplied by McMillan. At about that same time, Tom Houghton of H-S Precision developed the aluminum bedding block chassis for the Army’s M24 Sniper Rifle, then quickly phased it into his Pro-Series aftermarket fiberglass stocks, which were the first true drop-ins in the industry.

The first production rifles with laid-up fiberglass stocks appeared in mid-’80s. They included Weatherby’s Fibermark and Sako’s Fiberclass, both supplied by McMillan. At about that same time, Tom Houghton of H-S Precision developed the aluminum bedding block chassis for the Army’s M24 Sniper Rifle, then quickly phased it into his Pro-Series aftermarket fiberglass stocks, which were the first true drop-ins in the industry.

Concurrent with the development of the laid-up fiberglass stock came the injection-molded varieties. The dies are expensive, but once made, stocks can be pumped out quickly and very economically.

Injection-molded stocks are not as strong, light or as good as laid-up fiberglass stocks, but they are coming close on both counts.

So, to answer the question posed at the outset, “Whatever happened to walnut?” Synthetics and wood laminates, that’s what. You have only to peruse any current rifle catalog to see that together they outnumber traditional walnut-stocked rifles by a wide margin. Whatever aesthetic attributes these stocks may lack in the eyes of the more conservative among us, they more than make up for it in the fact that both make a superior gunstock.

Read Recent GunHunter Articles:

• Five Guns Worth Finding: These hunting guns are no longer made, but are well worth seeking on the used gun market.

• Stock Options: Got an inaccurate rifle? Maybe it’s time for a different handle.

This article was first printed in the August 2011 edition of Buckmasters GunHunter Magazine. Subscribe today to have GunHunter delivered to your home.