They may not be as accurate or flat-shooting as saboted slugs, but wide-bodied slugs continue to dominate the slug market.

For the better part of the 20th century, smoothbore shotguns and rifled or full-bore slugs were the only ordnance deer hunters in parts of the Midwest and Northeast could legally use.

Back then, slug shotguns had little more than a front bead for aiming. Slugs were big, slow and soft, which was fine for close-range shots at standing deer.

When saboted slugs and rifled shotgun bores came on the scene in the 1980s, some folks believed the full-bore or rifled slug was made obsolete.

It never happened. Today, 60 percent of slug sales are made up of common rifled slugs or full-bore slugs fired from smoothbore shotguns. These slugs are significantly less expensive than the saboted variety, and price is the biggest driver of American retail.

Sabot slugs, conversely, are designed for rifled-barrel shotguns. The slugs’ plastic sleeve or wad gripping the rifling grooves imparts a stabilizing rotation on the projectile.

A rifled barrel, however, must be dedicated to shooting sabot slugs. It can’t be used for turkey, waterfowl, small game or target loads, and — despite what you’ve read — a large portion of the slug-shooting public is reluctant to dedicate a gun exclusively to deer hunting.

A rifled barrel, however, must be dedicated to shooting sabot slugs. It can’t be used for turkey, waterfowl, small game or target loads, and — despite what you’ve read — a large portion of the slug-shooting public is reluctant to dedicate a gun exclusively to deer hunting.

The effective range of rifled slugs is considerably less than that of saboted loads. But most shots taken at woodland deer are within 100 yards. Using a rifled or full-bore slug is no disadvantage at this relatively close range, but only if you can place the slug where you want it.

Dealing with Finicky Barrels

The first and most important consideration in improving the accuracy of a smoothbore slug gun is the load.

You’ve undoubtedly heard it before, but it’s true: Every gun will shoot the same type and brand of slug a little differently. That’s because shotgun barrels have different internal diameters and choke constriction.

The loads vary in diameter as well. The differences might seem miniscule, but I guarantee if you try enough slugs, you’ll find one that your gun likes better than all of the rest.

Of course, the rifled slug has the ballistic coefficient of a bowling ball. Put the same engine in a Volkswagen Beetle and an Indy 500 racer, and head to the drag strip for comparison.

The rifled slug sheds half of its velocity in the first 50 yards and tends to destabilize rapidly at about 68-73 yards when said velocity drops below the speed of sound, about 1,200 fps. The slug’s advantage is its remarkable molecular cohesiveness. It deforms drastically but holds together on impact. Sure expansion also makes it an effective short-range load.

Remington, Winchester and Federal dominate the rifled slug market, offering loads of various sizes, weights and velocities in 12, 16 and 20 gauges and .410 bore.

Remington, Winchester and Federal dominate the rifled slug market, offering loads of various sizes, weights and velocities in 12, 16 and 20 gauges and .410 bore.

Brenneke offers full-bore slugs in the same gauges as well as the Foster-like K.O. slug. There have been a few other foreign and domestic incursions in the market over the years, but none have challenged the monopoly.

Slug Innovations

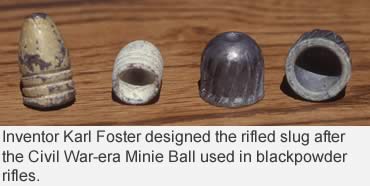

There have been a few improvements to the rifled slug over the years. Winchester redesigned its projectile in the early 1980s, making it more concentric, and increased its diameter to full-bore size. Federal followed in the late 1980s and redesigned its wads in the early 1990s. Remington, which had the smallest-diameter rifled slug, did its bore-filling redesign in 1993.

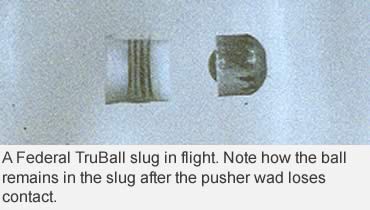

Then in 2004, Federal Cartridge made a major improvement to the rifled slug design with its Vital-Shok TruBall system. The unique design — essentially a polymer ball inserted into the cavity of a conventional rifled slug and driven by a unique pusher wad — doesn’t make the TruBall any more powerful than conventional rifled slugs. Nor does it extend the slug’s range. But it does make it much more accurate from shot to shot.

Then in 2004, Federal Cartridge made a major improvement to the rifled slug design with its Vital-Shok TruBall system. The unique design — essentially a polymer ball inserted into the cavity of a conventional rifled slug and driven by a unique pusher wad — doesn’t make the TruBall any more powerful than conventional rifled slugs. Nor does it extend the slug’s range. But it does make it much more accurate from shot to shot.

Winchester similarly went after a larger share of that huge rifled slug market in 2006 with its own RackMaster system — a Winchester Power Point rifled slug fitted with a black plastic pusher wad that serves much the same function as the TruBall’s ball and pusher wad.

The RackMaster has shown outstanding accuracy inside 80 yards in both smoothbore and rifled barreled guns with the same remarkable molecular cohesiveness that has made rifled slugs so effective on deer-sized game for decades.

Full-Bore Slugs

The original full-bore shotgun slug — and still the leading seller in that genre — is the German-made Brenneke.

Wilhelm Brenneke’s original design came in 1898 and remains remarkably similar today as the flagship of the company’s slug line. Designed for hunting boars in Germany’s Black Forest, the slug featured a cylindrical lead form with a discernible nose. It was solid lead with a larger diameter than the subsequent American-designed rifled slugs, with a fiber wad literally bolted to the rear of the slug.

The longer projectile and attached wad offered a larger bearing surface to keep the slug better aligned in the bore. It also was more stable in flight.

Then, as today, Brenneke designers sought penetration rather than significant expansion upon impact.

Two World Wars devastated the company’s factory and left the family with no male Brenneke heirs. Wilhelm Brenneke’s grandson, Dr. Peter Mank, has served as managing director for the last couple of decades.

The Brenneke shotgun slug line has expanded remarkably over the years, including a variety of slugs designed for rifled bores, but the smoothbore varieties — from the K.O. to the Black Magic Magnum — share the common base with the original design.

Full-bore slugs from PMC, Fiocchi, Wolf and a few other offshore manufacturers are commonly available, but Brenneke’s designs dominate the full-bore market.

The Heart of a Slug Gun

The Heart of a Slug Gun

In 1959, Ithaca Gun Co. built the first shotgun designed for slug shooting: the 12-gauge Deerslayer. It was simply a Model 37 pump action with a much tighter barrel and no forcing cone or choke.

It was accurate because slugs of the day filled the tight bore with no chance of tilting. Also, the absence of a choke and forcing cone eliminated any chance of the slug deforming.

The barrel remains the heart of any slug gun. Its length makes little difference in velocity. Shorter barrels, in fact, are stiffer and release the slug before harmonics can exert great influence on the projectile.

Unlike a rifled bore, which requires a 24- to 25-inch barrel to sufficiently stabilize the slug, a smoothbore barrel simply needs to get the slug started true to the bore.

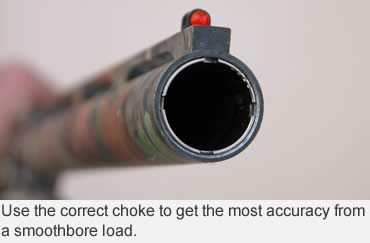

How tightly a slug fits in a barrel and the gun’s choke constriction are often the biggest factors in accuracy. A general rule of thumb is: The more open the choke, the better the barrel will handle slugs. However, in my experience, the barrel’s internal diameter makes a much bigger difference than its choke constriction.

While many guns with skeet or improved cylinder chokes shoot slugs well, I’ve seen many modified-choked shotguns that threw slugs into tiny groups at 50 yards.

I’ve found that Remington rifled slugs prefer cylinder bore, while Winchesters and Federals seem to shoot better out of a slight constriction. Full-bore slugs like Brenneke commonly prefer a slight constriction.

Also, the best smoothbore barrels for slug shooting are finely polished, particularly in the crown and forcing cone areas.

My most accurate slug smoothbores also have barrels fixed to the receivers. By firmly mating the barrel and receiver, you’ve taken the major harmonic effects (vibration) out of the equation. If you pin the barrel to the receiver, or epoxy it in place, it can later be removed for cleaning or to switch to a scattergun barrel.

My most accurate slug smoothbores also have barrels fixed to the receivers. By firmly mating the barrel and receiver, you’ve taken the major harmonic effects (vibration) out of the equation. If you pin the barrel to the receiver, or epoxy it in place, it can later be removed for cleaning or to switch to a scattergun barrel.

I really feel that if you want the best accuracy out of a smoothbore gun and full-bore slugs, you must mount optics on the gun. The finer you are able to aim, the more accurate you will be with the right load and barrel.

You shouldn’t be shooting much more than 80 yards, so low-magnification scopes (2x to 4x maximum) or illuminated reticle (red-dot) scopes work fine on smoothbore guns.

There are plenty of saddle-style scope mounts on the market that can be affixed to your shotgun’s receiver without any drilling or tapping, and they are fine for short-range shooting.

But if you are really serious about shot-to-shot consistency at longer ranges, you’ll find the saddle mounts move a little on each shot and can’t be affixed tightly enough to avoid that.

Drilling and tapping the receiver for a scope rail is the best way to go. The rail can always accommodate some sort of sight for turkey hunting, also, or could be removed entirely for waterfowl or small game hunting.

If you stay within the sensible parameters of smoothbore slug shooting (inside of 90 yards), use the right slug, and prepare your smoothbore barrel correctly, you’ll have a very effective deer gun.

Is Your Barrel Too Clean?

A smoothbore barrel should be cleaned more regularly than a rifled bore, primarily because the slug rides on the barrel walls. Conversely, a saboted slug never touches the walls in a rifled bore due to the sabot sleeves.

You will find, however, that a slightly fouled (two to three shots) smoothbore barrel will often be more accurate than one that is squeaky clean. The tolerances are tighter. I recommend forgoing the ritual of cleaning a slug gun barrel the night before opening day.

Read More Articles by Dave Henderson:

• Make It Shoot: Is your rifle shooting better patterns than groups? Here are the most common problems — and fixes.

• Trick Out a 10/22 Part I: With just a few simple tools, you can build a semi-custom .22 that looks good and shoots great.

• Trick Out a 10/22 Part II: How to convert the world’s most popular rimfire rifle to .17 Mach 2.

This article was published in the November 2009 edition of Buckmasters GunHunter Magazine. Subscribe today to have GunHunter delivered to your home.