By Jon R. Sundra

The line between standard and magnum cartridges has long been blurred.

There was a time when the term “magnum” was fairly well defined. I’m talking back in the ’60s and ’70s when the word pretty much meant a cartridge more powerful than normal and was usually based on the belted Holland & Holland case. In fact, in the eyes of many, if it didn’t have a belt, it couldn’t be a magnum — that’s how synonymous the two words became. As always, though, there were many exceptions to the rule. Back in its early days as a wildcat, for example, the .25-06 certainly provided magnum performance if the “standard” for the caliber was the .257 Roberts. Yet it was never called the .25-06 Magnum.

At the other end of the .25-caliber spectrum was the .256 Winchester Magnum, a bastard of a cartridge if ever there was one. Originally designed as a pistol cartridge, what limited popularity it achieved, it did so with the Marlin Model 62 Levermatic rifle. Based on the .357 Magnum pistol case necked down to .25 caliber, as a rifle cartridge it was pitiful, sending a 60-grain bullet of low sectional density and ballistic coefficient at 2,760 feet per second. If we again cite the .257 Roberts as representing the performance standard for the caliber, it would have qualified as a super magnum compared to the .256! Incidentally, I actually owned one of those Marlin Levermatics, and the .256 Win Mag was the cartridge with which I started my handloading career.

An even better example of confusing nomenclature is the .220 Swift. When it was introduced in 1932, it absolutely blew the doors off any other .22 centerfire cartridge, yet like the .25-06, it, too, never received the magnum accolade. Even when the .222 Remington Magnum was introduced in 1958, the Swift pushed the same-weight bullets about 500 fps faster, yet it was … well, just a Swift, not a magnum.

An even better example of confusing nomenclature is the .220 Swift. When it was introduced in 1932, it absolutely blew the doors off any other .22 centerfire cartridge, yet like the .25-06, it, too, never received the magnum accolade. Even when the .222 Remington Magnum was introduced in 1958, the Swift pushed the same-weight bullets about 500 fps faster, yet it was … well, just a Swift, not a magnum.

Like I said, there are many exceptions to the rule, but for the most part there was some thread of consistency throughout cartridge nomenclature. I guess when you get right down to it, a cartridge is regarded as a magnum if its performance — usually based on velocity, but not always, as in the case of shotshells — is higher than the nominal standard. Today we have many true magnums that have no belt, plus short magnums, ultra magnums and “enhanced performance” cartridges, so determining what those standards are is a lot more confusing than it used to be.

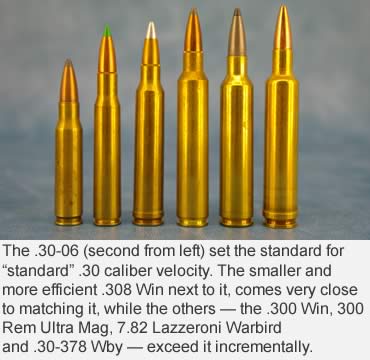

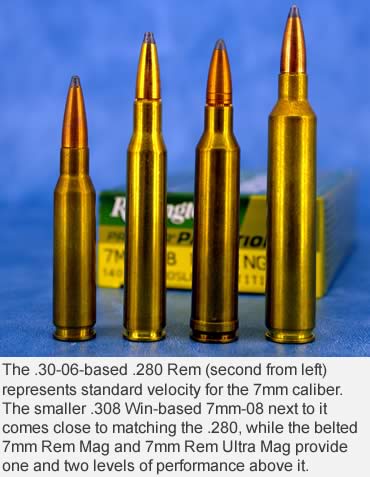

I do think, however, we would all agree that the performance standard for our two most popular hunting calibers, the 7mm and .30, are represented by the .280 Remington and the .30-06. In other words, a muzzle velocity of around 2,800-2,850 fps for a 150-grain 7mm bullet, and 2,750 or thereabouts for a 180-grain slug in a .30-06, represent standard cartridge performance for those respective calibers. Any cartridge that increases those nominal velocities by 150-200 fps would qualify as a magnum, whether called that or not.

Continuing the preceding thread, the 7mm Remington and .300 Winchester best exemplify what most of us mean by magnum in those respective calibers. Of course, we now have the 7mm and .300 Winchester Short Magnums, which duplicate the aforementioned rounds with a shorter, squatter case, and without that once almost-mandatory appendage known as a belt.

Continuing the preceding thread, the 7mm Remington and .300 Winchester best exemplify what most of us mean by magnum in those respective calibers. Of course, we now have the 7mm and .300 Winchester Short Magnums, which duplicate the aforementioned rounds with a shorter, squatter case, and without that once almost-mandatory appendage known as a belt.

Then we have in those same two calibers the 7mm and .300 Remington Ultra Mags, both of which deserve that superlative moniker because they provide another significant step up in performance over … “standard magnums” if you will, which has to qualify as an oxymoron if ever there was one!

What in recent years has further blurred the lines between standard, magnum and ultra magnum performance is best characterized by Hornady’s original Light Magnum line of enhanced performance ammunition. By using proprietary loading procedures and propellants specifically formulated for them, Hornady was able to boost velocities in non-magnum cartridges by as much as 140 fps over the nominal standards, and with no increase in pressures. After a couple of years, Hornady applied that same technology to magnum calibers, but they felt they had to somehow distinguish it from non-magnum calibers, so they called it Heavy Magnum, even though the velocity gains averaged about the same.

For example, the Light Magnum 165-grain .308 Win load clocked 2,840 fps compared to 2,700 for the standard loading. In .300 Win, the Heavy Magnum load exited at 3,120 fps, or 170 fps over the standard load. Thankfully, the Hornady folks realized the potential for confusion and this year have chosen to change the name to Superformance, and it applies to all such enhanced loadings whether magnums or not.

Further blurring the lines between standard and magnum performance is that Hornady has applied this same technology in its development of proprietary cartridge lines for Ruger, Thompson/Center and Marlin. The .300 and .338 Ruger Compact Magnums, the .30 TC and the .308 and .338 Marlin Express are all examples of cartridges that provide significant more velocities than they could otherwise given their case capacities.

Even more dramatic, though, are the performance gains achieved when these same loading techniques are applied to classic lever action cartridges like the .30-30, .35 Rem, .444 Marlin and .450 Marlin, in conjunction with Hornady’s development of Flex Tip bullets that allow spitzer-shaped projectiles to be used in the heretofore verboten tubular magazines of classic lever-action rifles like the Marlin 336 and Winchester Model 94. The gains in velocity, coupled with the flatter trajectories of these much more streamlined bullets, have elevated the overall performance of these old guns to where they would qualify as magnums when compared to the standard loadings and the flat- or round-nosed bullets these guns were traditionally saddled with.

Even more dramatic, though, are the performance gains achieved when these same loading techniques are applied to classic lever action cartridges like the .30-30, .35 Rem, .444 Marlin and .450 Marlin, in conjunction with Hornady’s development of Flex Tip bullets that allow spitzer-shaped projectiles to be used in the heretofore verboten tubular magazines of classic lever-action rifles like the Marlin 336 and Winchester Model 94. The gains in velocity, coupled with the flatter trajectories of these much more streamlined bullets, have elevated the overall performance of these old guns to where they would qualify as magnums when compared to the standard loadings and the flat- or round-nosed bullets these guns were traditionally saddled with.

No sir. The term magnum doesn’t have quite the same connotations it once did. There are cartridges today that produce magnum and even super-magnum performance, yet are not so designated. The 7.82 Lazzeroni Warbird and .460 Dakota are consummate examples.

Then there cartridges that wear a belt and don’t qualify, such as the 6.5 and .350 Remington Magnums; they only duplicate the performance of the 6.5-06 wildcat and the .35 Whelen, respectively. And last are cartridges that, through enhanced loading techniques and the use of specially formulated propellants, find themselves in no-man’s land between standard and magnum performance.

In the final analysis, what difference does it really make? Thanks to our penchant for trying to pigeon hole everything into neatly defined categories, we find ourselves more frustrated than ever. But, for guys like me, it’s just one more thing to write about!

Read More Articles by Jon R. Sundra:

• The Unappreciated .260 Remington: Although 6.5s have been dominating long-range shooting, hunters still think of the .260 Rem as a kid’s cartridge.

• Can You Buy Shooting Skill?: There’s no substitute for practice, but some gear items can improve accuracy.

• Nosler Custom Model 48: This step down from the Custom Limited Edition is a semi-production gun offered in 10 chamberings.

This article was published in the July 2010 edition of Buckmasters GunHunter Magazine. Subscribe today to have GunHunter delivered to your home.