Your heart palpitates for a custom chambering, but think before you leap.

Forty years ago, as a new shooter and handloader, I was wild about wildcats. Not the furry, spotted kind. The mysterious, esoteric, hot-shooting, custom-formed brass kind.

Cartridges like the .22 Varminter, the .224 Clark, the .243 Page Pooper and the .219 Donaldson Wasp sounded wild and remained that way because they were so rare that none of us Dakota kids ever saw one.

Wildcat cartridges were as mysterious and unattainable as pinup girls. We lusted after them.

These days, I consider most wildcats to be tame cats. The wild has been taken out of them in several ways. First, many have been legitimized. The .243 Page Pooper became the .243 Winchester in 1955. Remington made the .22 Varminter its popular .22-250 Rem in 1965, and the .25-06 Niedner the .25-06 Remington in 1969. Second, many of the rest, under the heartless gaze of today’s chronographs, don’t perform quite as well as initially advertised. Third, recent factory cartridges outperform many old wildcats and do virtually anything any hunter might like to do with a bullet. Fourth, chambering rifles and building ammunition for oddball cartridges is time-consuming and usually more expensive than reloading factory cartridges.

Despite all this, some wildcats remain viable because they address unmet needs in the commercial market — particularly in handguns, benchrest shooting and AR-15 platforms. And some shooters just like a challenge or something different. Others just enjoy fiddling around the reloading room. It’s an engrossing hobby. For the average hunter or shooter, there are darn few wildcats that do more than factory cartridges already do, so why fool with them?

Wildcat Definition

Wildcat Definition

A wildcat is a factory cartridge that has been reshaped to perform a specific task such as 1) Improve brass life for more reloads; 2) Increase powder capacity for more speed and energy; 3) Fire smaller-caliber, more streamlined bullets for flatter trajectory and less wind deflection; 4) Improve accuracy; 5) Reduce noise (subsonic); and 6) Function in a specific action (super-short actions, AR-15s, handguns, etc.) By definition, wildcats are not loaded and sold as factory ammunition for standardized chamberings in factory-built rifles, nor are they recognized by SAAMI.

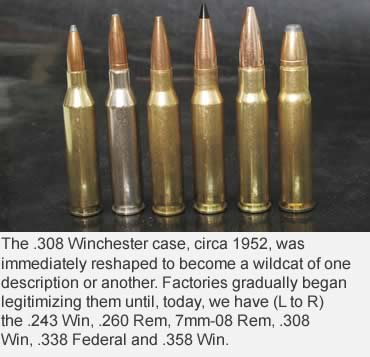

Once you understand that wildcats start from factory cases, you begin to see relationships. The .30-06 was necked down to the .25-06, .270 and .280. In the other direction, it got necked up to .338 and .358. Same thing happened to the .308 Win, giving us the .243 Win, .260 Rem, 7mm-08 Rem, .338 Federal and .358 Win. How manufacturers missed adopting the wildcat .257 and .270 versions is beyond me.

These factory cartridges that wildcatters rely on for their basic platforms are known as “parent” cartridges. Once a wildcat is adopted by a manufacturer and recognized by SAAMI, it is no longer a wildcat.

A Bit of Wildcat History

Winchester pointed the way toward wildcatting shortly after the appearance of metallic cartridges. They necked down their popular .44-40 blackpowder cowboy cartridge to create the faster, flatter-shooting .38-40 around 1874. The advent of smokeless powder and the .30-30 Win in 1894 inspired wildcat modification of that case, but it was soon overshadowed by the 7x57 Mauser and .30-06, both rimless cases better adapted to function through vertical-stack magazines in bolt-action rifles.

Because the .375 H&H, .30-06 and .270 Win were judged adequate for all North American big game, early wildcatting centered around the need for small-caliber, high-velocity varminting cartridges from 1930 to 1960. Amateur and professional gunsmiths like P.O. Ackley, Harvey Donaldson, Grosvenor Wotkyns and others tweaked and tuned an impressive variety of wildcat .22, .24 and .25 calibers.

Because the .375 H&H, .30-06 and .270 Win were judged adequate for all North American big game, early wildcatting centered around the need for small-caliber, high-velocity varminting cartridges from 1930 to 1960. Amateur and professional gunsmiths like P.O. Ackley, Harvey Donaldson, Grosvenor Wotkyns and others tweaked and tuned an impressive variety of wildcat .22, .24 and .25 calibers.

By the late 1960s, enough of the best (.22-250 Rem, .243 Win, 6mm Rem, .25-06 Rem) had been legitimized as factory rounds that experimenting tapered off. Why reinvent the wheel? Roy Weatherby cranked up larger calibers with his famous family of big game rounds based on the .375 H&H belted case in the 1940s.

The short-fat cartridge craze started in the 1970s with the .22 and 6mm PPC benchrest cartridges based on the .220 Russian, which was itself a shortened version of the 7x39 AK-47 round. The PPCs set accuracy records and soon became commercially available. This may have inspired the strong line of proprietary Dakota cartridges based on the fat .404 Jeffery case, and those in turn may have led to the .300 WSM and its derivatives, the .300 RSAUM and its family and finally the Winchester Super Short Magnums, all of which appeared after 2000.

New as they seem, most were created as wildcats long ago. The 7mm WSM is nearly identical to an old wildcat called the 7mm Gradle Express. In fact, so many basement gunsmiths have tweaked and fiddled with so many wild ideas that almost nothing is new under the sun. Wildcats continue to emerge in calibers as large as .775! The wildcatting practice will probably never end.

We’re Supplied, Thank You

We’re Supplied, Thank You

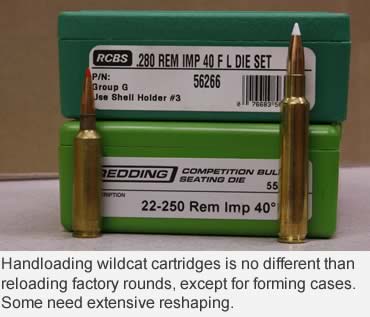

Essentially, while our major manufacturers have rarely beaten wildcatters to the punch, they’ve always won the popularity wars because it’s easier for the average shooter to buy factory rifles and ammunition. If a .22-250 Rem spits factory-loaded bullets 3,700 fps, why would you find a gunsmith to rechamber your rifle to a .220 Weatherby Rocket that only adds 100 fps to that speed? You’d have to then buy .220 Swift cases and custom reloading dies, and fireform cases and build/test various combinations of power/primer/bullet to figure out what worked best. Only then could you load up enough rounds to go prairie dog shooting or coyote hunting.

Now, it’s true that there are some over-the-top .22 wildcats that will churn out nearly 5,000 fps velocity, but they’ll burn a barrel to cinders in 300 rounds or less. Other than that, there isn’t much most wildcats can do that a factory round can’t at a lot less expense and trouble. Even if you handload, it’s a lot cheaper/easier with factory rounds than wildcats. For one thing, you don’t have to rechamber your rifle. For another, you don’t have to fireform brass. For yet another you don’t have to worry about running out of loads during a hunt, with no place to get more.

Still . . .

There’s just something about pulling out a rifle no one else has. “Whacha got there, a .260 Rem?”

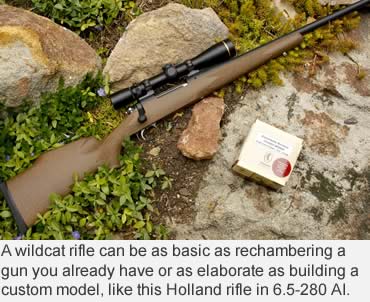

“No, it’s a .257 Ackley Improved.” Great snob appeal. Never mind that it won’t do anything a standard .25-06 Rem can’t do. Well, maybe a trifle more, since it’s on a short action. Actually, some of the best, most efficient, easiest-to-live-with wildcats are the Ackley Improved series, a great place to start for anyone interested in wildcats. Basically, an AI is a standard cartridge/chamber that has been enlarged slightly by straightening the body taper and flattening the shoulder angle to 40 degrees. This results in slightly more powder capacity and slightly higher velocity, but its biggest benefit might be increased case life.

The AI shape seems to preclude much of the brass stretching common to more tapered rounds. You trim less often and load more often before case failure. But that’s not all the good news. If the headspace isn’t changed appreciably (shoulder isn’t set farther forward) you can fire factory loads in an AI chamber, fire-forming cases as you do. There’s a slight sacrifice in velocity with factory rounds, but accuracy rarely suffers. Your brass is then ready for sizing and typical handloading through your AI dies. Most AI cartridges will add 2 to 8 percent velocity to parent rounds. AI chambers can be easily cut into existing barrels at minimal cost, too. Figure from $80 to $300, depending on the gunsmith.

Some popular, proven AIs include the .22-250, .243 Win and .257 Roberts. The .280 AI is so good that Nosler began chambering for it in their custom Model 48 rifles and selling loaded ammunition, so I guess it’s not a wildcat anymore. Some folks argue that AI cartridges never were wildcats, just improvements of factory cartridges. I guess their way of thinking is that if factory loads fit and function in the chamber, it ain’t a wildcat.

Some popular, proven AIs include the .22-250, .243 Win and .257 Roberts. The .280 AI is so good that Nosler began chambering for it in their custom Model 48 rifles and selling loaded ammunition, so I guess it’s not a wildcat anymore. Some folks argue that AI cartridges never were wildcats, just improvements of factory cartridges. I guess their way of thinking is that if factory loads fit and function in the chamber, it ain’t a wildcat.

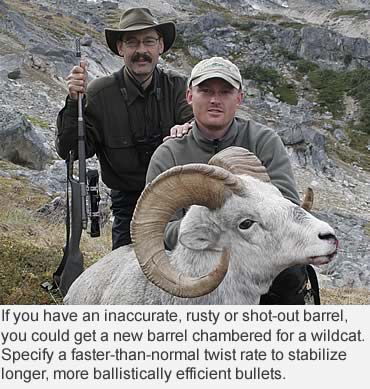

Save the Old Rifle

If you have an inaccurate, rusty or shot-out barrel, you could get a new barrel chambered for an AI or wildcat. Specify a faster-than-normal twist rate to stabilize longer, more ballistically efficient bullets, and you’ll minimize wind deflection and increase retained energy downrange. A standard .22-250, for instance, will have a 12- or 14-inch twist, good enough to stabilize perhaps 60-grain bullets. Change that to an 8-inch twist, give it an AI chamber and you’ll be able to shoot 75-grain bullets at 3,350 to 3,450 fps, depending on barrel length. Makes for one heck of a hot coyote rifle and doubles for whitetails and pronghorns where legal. Similar things can be done with .243s, .25-06s, etc.

Think Before You Leap

Study wildcats long and hard before you buy into one. Check their claims against today’s factory cartridges to determine if you’re truly gaining anything in performance, convenience, precision, longevity or anything else. Chances are there’s a factory round that comes so close, your wildcat isn’t worth the effort. On the other hand, if you like something different, there’s no reason you can’t be a wild and crazy wildcat shooter. Your gunsmith will love you for it.

This article was published in the October 2009 edition of Buckmasters GunHunter Magazine. Subscribe today to have GunHunter delivered to your home.