By Ralph M. Lermayer

Muzzleloading pellets from IMR prove their worth on call-happy pigs in South Texas.

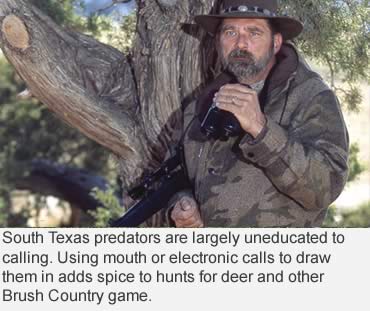

I own two FoxPro electronic predator calls. Actually, truth be known, I own one and my wife, Laura, owns the other. Last September, I was invited on a hog hunt in South Texas to field test IMR’s new muzzleloader propellant, White Hots. The primary hunt objective was to take big hogs coming to corn feeders, but the Texas coyote and bobcat populations are so good, I made sure my lanyard was full of mouth calls and at least one remote-controlled electronic call was in the pack.

It was very hot and humid, bumping 100 degrees in the shade and with 70 percent humidity - pure misery. The action was understandably slow except for the last half-hour of daylight when temperatures dropped and critters began moving.

Twenty minutes past adequate shooting light, as I packed up my gear waiting for the guide to pick me up, four hogs showed up at the feeder. They were promptly run off by the approaching headlights. Six hunters on six different stands scattered over the 10,000-acre ranch all reported the same first-night experience. Night one brought no chance to test the White Hot pellets in a real-world hunting situation.

Hodgdon developed the pellets and released them under the IMR brand name. The wisdom of such decisions is well beyond my pay grade, but regardless of the name, the natural tendency will be to compare them to the only really successful blackpowder substitute on the market, namely Pyrodex, and specifically Pyrodex Triple Seven pellets.

I do a substantial amount of serious muzzleloader hunting every year and can’t risk a trophy on unreliable blackpowder substitutes. I have tried them all. Most perform reasonably well from the bench, but in the field, it’s a different story. One brand starts losing power and deteriorating as soon as you open the container. That same brand shifts point of impact radically as temperatures change. Another brand delivers shot-to-shot variations so large, its practical field use is nonexistent. Only Pyrodex Triple Seven goes off consistently with 209 primers in an inline or with musket caps in a sidelock, and gives me the same performance regardless of weather. That’s the performance I demand and the standard against which I chose to measure the new White Hots. The results were a surprise. There is no difference!

My primary muzzleloader battery consists of three rifles, each chosen for a particular need. A 24-inch-barreled T/C .50-caliber Pro Hunter sees the majority of the work when longer shots are likely. At 200 yards, with a 290-grain Buffalo Bullet over two Pyrodex Triple Seven pellets, it’s a consistent 3-inch shooter.

That same load in a 20-inch-barrel H&R Huntsman is my choice for hunting at close range and in thick cover. The compact gun is also ideal for close-quarters treestand hunting.

Where scopes aren’t allowed or inlines aren’t legal, a custom .50-caliber Colt sidelock musket fired by musket caps and fitted with a fast 1-in-28 twist, 22-inch barrel and a peep sight gets the nod. I start the load with a small amount of FFF blackpowder to ensure ignition. Just a few grains does it. Then I top it with two 50-grain Triple Seven pellets and a 290-grain Buffalo SSB. This combination delivers a 4-inch group at 100 yards with iron sights. That’s as good as my eyes can do with irons.

Where scopes aren’t allowed or inlines aren’t legal, a custom .50-caliber Colt sidelock musket fired by musket caps and fitted with a fast 1-in-28 twist, 22-inch barrel and a peep sight gets the nod. I start the load with a small amount of FFF blackpowder to ensure ignition. Just a few grains does it. Then I top it with two 50-grain Triple Seven pellets and a 290-grain Buffalo SSB. This combination delivers a 4-inch group at 100 yards with iron sights. That’s as good as my eyes can do with irons.

Each of these rifles is set up for that same load and is never changed. Here’s the surprise: In every case, in both rifles, two 50-grain White Hot pellets delivered the same bullet to the same point of impact as two 50-grain Triple Seven pellets.

The only real difference I could detect (except for the fact that this blackpowder substitute is pure white) was slightly less crud buildup after several shots with the White Hots. All substitutes leave a carbon ring at the powder/bullet junction. That ring thickens with each shot and must be removed to maintain accuracy. With Triple Seven, it takes two passes with a slightly water-dampened patch to get it out. With the White Hots, one pass and it is gone. For that reason alone, once my supply of Triple Seven is used up, I’ll be making the switch to White Hot pellets for all my rifles.

Other than that, from velocity to point of impact, it’s a dead ringer for the Hodgdon product. For those who care about such things, I did compare both over the chronograph. The accompanying chart shows the results. As to the accuracy difference, I could detect none, and that’s in good-shooting rifles I am familiar with.

Back To the Hunt

Day Two showed a little more promise. For the morning hunt, no hogs showed. Out of boredom, I decided to crank up the remote caller. Not wanting to use loud, screaming rabbit sounds for fear of running off any approaching hogs, I chose a subtle but effective woodpecker-in-distress sound. It immediately pulled in several curious deer and, strangely, a whole pack of raccoons that hung around the call until the truck came to pick me up.

Back at camp, Randy Smith had managed to put the coup de grâce on one sow weighing about 100 pounds — perfect eating size. The rest of us came up empty on the morning of day two.

The evening hunt, however, proved more fruitful. Two nice javelina met their match under Chris Hodgdon’s stand, and Sam Fadala put the kibosh on a nice sow that tipped the scales at about 200 pounds. All shots ranged from 75 to 100 yards, and even in the blazing heat and steaming humidity, the White Hots did their thing in every case. The rest of us drew zero comers.

The evening hunt, however, proved more fruitful. Two nice javelina met their match under Chris Hodgdon’s stand, and Sam Fadala put the kibosh on a nice sow that tipped the scales at about 200 pounds. All shots ranged from 75 to 100 yards, and even in the blazing heat and steaming humidity, the White Hots did their thing in every case. The rest of us drew zero comers.

The Strange Morning

The last morning found me sitting high on an open tripod stand. Radiating out from the stand like the spokes of a wheel were six senderos, lanes about 20 yards wide cut through the Texas brush. These had grown over with grass and extended from 100 to 200 yards. That’s how it’s done in Texas. At the end of one lane, 120 yards away, stood a tripod-mounted corn feeder set to go off about 7 a.m. Two small bucks milled around the feeder in obvious anticipation.

The remote call was set in one of these cuts 50 yards from my stand. A feather decoy on a shaft added a bit of visual attraction. At 6:45, several 150-pound black hogs appeared at the far end of one of the lanes about 200 yards distant, obviously feeding toward me. I waited. When they slowly made it to within 150 yards, I thought I’d liven things up a bit. Using my remote control, I sent a series of wild boar fighting sounds their way. Their heads spun around, and they picked up the pace, heading for the call.

I swung the Pro Hunter their way and readied for a duck-soup shot when I caught a fleeting glimpse of the biggest wild hog I have ever seen in my life — at least 400 pounds with huge tusks I could clearly see with the naked eye. He sped across one of the open lanes, heading for the feeder. The smaller hogs were now coming faster. Decision time.

I moved the muzzle toward the feeder, forgetting the little guys, and readied for the shot where I thought the big tusker would emerge. The smaller hogs kept heading for the boar fight sounds coming from the FoxPro, and I didn’t think to turn it off. I found the feeder in my scope and waited for the big guy to show. He did, but he no more than stuck his big head into the clearing when one of the bucks stomped his feet, lowered his pretty 6-point rack and ran the boar back into the brush. He circled in the brush and reappeared on the other side for a split second. I was warned to his new approach by that same buck promptly running him back into the brush. He was laying claim to the corn and obviously had no fear of this boar.

I was also alerted to the arrival of the pack of smaller hogs at my call by the eerie sound of plastic and metal being crunched to smithereens. I stayed focused on the feeder, ignoring the sounds of my call being destroyed, now joined by a chorus of snarling grunts and squeals from the small hogs as they turned on each other in a fight-driven frenzy.

The call sounds abruptly stopped. The small bunch scattered into the brush, and the big boar never reappeared. It took all the forces of self-control I could muster to stop me from putting a bullet into that little *#&% buck’s head.

Eventually, all became still, and except for my pounding heart, quiet. Even the bucks fed off, but I waited, hoping Mr. Big would show. He didn’t. When the truck arrived, I climbed out and retrieved what was left of the electronic call and my feather decoy — not much.

Back at camp, I was meekly informed that my guide knew that huge hog was in that pasture. I hadn’t been told. Apparently, if you tell clients he’s there, over 500 pounds of big black tusker, then the hunters will pass on normal hogs and wait for him. The ranches want and need lots of small hogs killed, so they choose not to mention the monster.

Such megahogs are becoming more numerous in Texas, where problem hogs are routinely live-trapped. The trappers, instead of hauling them off, will castrate the bigger boars and turn them out. The result, huge boars with huge tusks since they no longer have the will to fight (even deer), and these enormous boars bring a substantial trophy fee as opposed to run of-the-mill cull/eating porkers.

Such is the way of things when you spend a lot of time in the field. Strange things happen, and the addition of a remote call always ups the excitement factor. All was not lost, however. Several hogs were taken, proving the worth of the new pellets. The shattered remnants of that trashed high-dollar call now sit in the FoxPro Museum.

There was one bit of good news: Turns out, it was Laura’s call I grabbed.

This article was published in the Winter 2009/2010 edition of Buckmasters GunHunter Magazine. Subscribe today to have GunHunter delivered to your home.