By Ralph M. Lermayer

A practical hunter’s guide to riflescopes, binoculars and rangefinders.

The subject of optics for hunters is one that gets a lot of press. Rightfully it should, since our choice of scopes, binoculars and now rangefinders can literally determine the success of a hunt. The choices are endless, as each manufacturer extols the virtues of its particular line, and with so much to choose from, it can get confusing. There are, however, some basic philosophies that can be applied when making those choices. It boils down to matching the dollars you spend to your particular needs. Contrary to a lot of optics reports, you may discover you don’t always need the highest-dollar glass to get the job done.

Riflescopes

These days, every major scope manufacturer offers a perfectly acceptable scope. There’s still some real trash being imported that shows up every so often, but serious shooters ignore them.

There was a time when the name alone indicated top-quality glass, but today, most of the majors offer two or three tiers of quality in order to compete in every level of the market. Simply carrying a well-known name doesn’t necessarily mean high-end glass anymore.

At the top end, manufacturers hold nothing back and put everything they know about building superb optics into play. Here, you’ll find Nikon Monarch, Bushnell Elite 4200, Leupold VX III, Weaver Grand Slam, Burris Signature, Zeiss, Swarovski, Kahles and other highly recognized names. These are pricey, but for good reason.

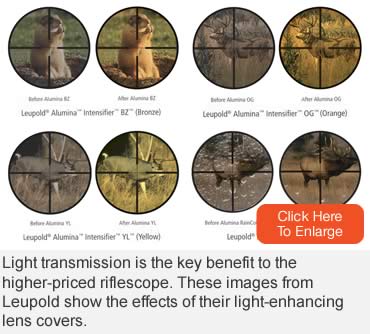

First, extreme care is taken in their construction with every step monitored, checked and inspected. Second, for those built in Europe, a weak dollar in relation to the Euro raises their retail cost here, and last, the quality of the glass and its final coating must be perfect. That last step affects the single most crucial factor that separates the high-end glass from the medium and low-end choices: light transmission.

You will never get 100 percent of the available light outside a scope delivered to the eyepiece. The internal optics diminish the light a little through every lens. It is relatively easy to get 90 percent light transmission, and that’s what your low- and medium-end scopes usually deliver. A little more attention to glass and coating is required to reach 92 percent, and 95 percent takes a lot of painstaking attention to each and every detail.

The difference to you, the user, is between 15 to 30 minutes of additional shooting time. With the higher light transmission, you can effectively see well enough to shoot earlier as the day breaks and later as the sun sets. Is it important? To many it is, because those early and late moments are usually the times of highest game activity.

The only practical difference between the top-of-the-line and the medium end, such as Bushnell’s Banner, Nikon Trophy, Leupold Wind River and such, boils down to that extreme early and late shooting time. It is minutes versus dollars. If those early and late minutes are not important, as is the case with varmint hunters, antelope hunters or any situation where you rarely find yourself out before light and back after dark, you don’t need to bear the expense. In those situations, medium-end optics will serve you well and save a pile of money. Structurally, they’re every bit as rugged and clear as the high-end stuff.

The only practical difference between the top-of-the-line and the medium end, such as Bushnell’s Banner, Nikon Trophy, Leupold Wind River and such, boils down to that extreme early and late shooting time. It is minutes versus dollars. If those early and late minutes are not important, as is the case with varmint hunters, antelope hunters or any situation where you rarely find yourself out before light and back after dark, you don’t need to bear the expense. In those situations, medium-end optics will serve you well and save a pile of money. Structurally, they’re every bit as rugged and clear as the high-end stuff.

Fixed or Variable?

This is almost a moot point as it’s getting harder and harder to find good fixed-power optics. I like fixed powers on some rifles, most notably my saddle guns as well as certain muzzleloaders. They are rugged, and you can usually get a lot more quality (read light transmission) for a lot less money.

For deep-cover hunters, where the range is likely 150 yards or less, a fixed 4x or 6x makes sense. For the rest, variables get the nod. For general hunting, including shots at big game up to 600 yards, a 3-10x is about ideal. A 4-12x, as long as it doesn’t sacrifice eye relief, is also a good choice.

For the varminter, whose targets are small and the range often long, a 4-16x is close to ideal. Higher powers will cave in and wiggle (mirage) in the heat of the day, and experience has proven that most varmint hunters will leave them at 14x all day.

In spite of the variable options, most big game scopes spend the majority of their time at midrange, usually 4x to 6x. But for fast action in close cover, the ability to shift to a fast-acquisition 3x is a boon. Equally important is the ability to crank up to max for a long poke or when sighting-in at the range for precise bullet placement.

While all the variables from the majors are built rock-solid internally, you need to pay attention to the shift in eye relief as you roll through the power levels. Some, even from the well-known manufacturers, will cause you to crawl up closer to the scope at high magnification. If you’re using a hard-kicking magnum or are heavily clothed, that can be a real problem. Check the scope’s eye relief at the counter before you buy.

As to the low-end cheapies, avoid them. They have poor light transmission, track badly and will inevitably let you down.

Variables make sense. Today’s high-end and midrange variables are reliable and rugged, and the top-selling style worldwide.

Binoculars

Often, the success of a hunt hinges on the ability to spot game before it spots you. I spend an average of four months out of the year hunting. During that time, I spend at least a third of every daylight hour staring through a binocular.

Often, the success of a hunt hinges on the ability to spot game before it spots you. I spend an average of four months out of the year hunting. During that time, I spend at least a third of every daylight hour staring through a binocular.

Most hunters understand the need for good glass in such country, but they are equally vital in deep cover, taking apart the brush for the slightest telltale giveaway of movement. Much of what was said about the quality of riflescopes holds true for binoculars, but unlike that scope, which only gets brief looks, you will spend hours looking through binoculars.

Here, the quality of glass as well as light transmission is a big factor. Years ago, when I could barely afford it, I skimped for months to buy a $700 pair of Zeiss 10x40s. They have served me well, been on rough hunts around the world and have never let me down.

Today, quality optics as good as my 30-year-old Zeiss’ can be had for far less than I paid those many years ago. Like scopes, prices on binoculars can run from a pittance to well into thousands, but like scopes, if you only use them for the occasional glance, you don’t need the high price tag. Midrange glass from Nikon, Leupold, Alpen and Bushnell and such do a fair job for about $150 to $200.

If you will be looking through binoculars for hours on end, then the mid- and low-end choices will soon give you raging eyestrain and headache, ruining your hunt. If you need the finite detail and clarity that will let you use them for hours and determine if that buck at 600 yards has headgear worth the hike, opt for Zeiss, Swarovski, Bushnell Elite, Leupold Gold Ring, Nikon LX, Steiner Peregrine or Leicas. They are all superb glass and pricey, but you will never regret the money spent. Which you choose is purely a matter of personal preference. Weights vary, as do exterior finish and ergonomic design, but they are all optically excellent.

I still use the old Zeiss’ that have served me so well through decades, and interestingly, I see them currently for sale for $699, about what I paid decades ago. But, I have tested and used a Nikon 10x42 LX, a Bushnell 10x42 Elite and a Steiner 10x42 that are every bit their equal. All are midsize roof-prism designs that are easy to pack, not excessively priced, built to take rough treatment and won’t break the bank.

Size

Most low-cost, ultra-small, shirt-pocket binoculars are all but useless for the hunter. Light transmission and clarity are poor, and the same holds true for the midsize $39 bargain glass found hanging in the discount houses. A rank horse, bad weather or a bumpy ATV ride soon renders them useless. But even with the compacts, there can be exceptions.

If you’re willing to spend the money, you can find ultra-small units that are impressive. Their size limits the light transmission, but in all but extreme conditions, they’ll get you by. I have a Swarovski 8x20 B that folds up to about the size of a pack of smokes. When turkey hunting, varmint calling or in any situation where movement must be kept to a minimum, I can ease them from my shirt pocket to my eyes, then back with minimal one-hand movement.

It takes a lot of engineering to get quality in a mini. Last I checked, they ran about $800, which is a lot to shell out for a pair of minis, but the clarity and convenience is worthwhile. They live in my pack as an ultralight backup should my primary glass be lost or broken. I won’t go on a hunt without good glass, and there’s a comfort in having a spare at hand. Special close-cover applications, and as a lightweight spare are the only place for the ultra compacts.

Rangefinders

It’s hard to understand how we lived without them. The early models were not totally reliable, but today’s offerings are vastly improved. I’ve used the latest high-end models from Nikon, Bushnell and Leica, and all have proven more than adequate. As is the case with anything, quality dictates price.

There is no doubt the current Leicas can access small targets faster even in dim light than the others, with Nikon’s Laser 800 a close second and less expensive. Bushnell’s Elite 1500 is equally quick and sensitive. They are good units, and for those who can afford them, a good choice, but for most hunters, the lower-priced entry-level units will accomplish everything you need.

The reason is in the practical application of rangefinders in the field. It’s rare that you’ll use them to actually range an animal’s body, which takes the sensitivity and speed of the high-end units. Instead, you usually range to something large and contrasting near the target like a rock, tree or brush. Stand hunters will usually range several large objects around the perimeter of their stand, memorize the ranges and put them away.

For that kind of use, the inexpensive entry-level units like Bushnell’s Scout or Yardage Pro series are all you ever need. Six-hundred- to 800-yard capability is really the most practical for rifle hunters, and the 400-yard max on the smaller units is more than any archer will ever need. You do want a unit with at least a 6-power magnification, 8 power is better yet, and you want to be able to focus the eyepiece for your eyes.

I own and regularly use both a high-end Nikon and an entry-level model. The Nikon can pinpoint and isolate an antelope at 700 yards, but I could probably get by ranging a nearby bush with the cheaper unit and do just as well.

There’s a world of great optics out there, and getting exactly what you need doesn’t have to be a budget-busting situation. The midrange optics made today are as good as many of the high-end or elite choices from just a couple decades back. Avoid the bargain-basement stuff, and match your choice to your needs, but don’t skimp. It’s an investment that will last a lifetime.

This article was published in the October 2005 edition of Buckmasters GunHunter Magazine. Subscribe today to have GunHunter delivered to your home.