Every shooter needs good hearing protection. Here’s what’s available.

If your hair is turning white or mostly gone, you may remember two of the most famous handgunners of the 20th century. Elmer Keith, an Idaho cowboy turned gunwriter, was almost single-handedly responsible for getting the .44 magnum introduced. His most memorable book was titled, “Hell, I Was There!”

After retiring from highly adventurous service with the U.S. Border Patrol, Bill Jordan had a second career demonstrating his lightning-fast draw and writing for a gun magazine. He also authored an entertaining and informative handgun combat book titled, “No Second Place Winner.” My autographed copy is a prized possession.

I once watched these two icons attempt a conversation. It consisted mostly of “What?” “What did you say?” “I can’t hear you!” bellowed loud enough to make onlookers flinch. These storied handgunners began shooting back in the days when hearing protection was largely unknown. By the time I finally met them, they were as deaf as that infamous post.

In the past half-century, I’ve hunted with, tested and shot an unimaginable number of firearms ranging from .22 rimfires to big bores like the .458 Lott and .50 BMG. Yet my hearing remains pretty good. Any damage it has suffered can be blamed on the early years I spent shooting .22 Long Rifle loads without the benefit of earplugs or muffs.

I’d long heard the lowly rimfire was responsible for more damaged hearing than any centerfire rifle or handgun. Because .22 rifles weren’t uncomfortably loud, like most shooters I blithely ignored that information and didn’t bother with earplugs when plinking or rabbit hunting. One day I was working my way through several boxes of .22 LR rounds while testing rimfire rifles for accuracy, and developed a low-grade headache.

I’d long heard the lowly rimfire was responsible for more damaged hearing than any centerfire rifle or handgun. Because .22 rifles weren’t uncomfortably loud, like most shooters I blithely ignored that information and didn’t bother with earplugs when plinking or rabbit hunting. One day I was working my way through several boxes of .22 LR rounds while testing rimfire rifles for accuracy, and developed a low-grade headache.

“Could the .22 be causing this?” I wondered, and put on a pair of earmuffs. In five minutes, the headache went away — and my groups suddenly shrank in half! The .22 didn’t sound all that loud, but the reports were causing an unconscious flinch. That made a believer of me, and now I religiously wear some kind of ear protection when shooting rimfires.

Hearing can be permanently damaged when you’re exposed to sustained sounds exceeding 120 decibels (dB). A .22 rimfire rifle generates 126 dB. That’s just above the “that hurts!” level of 120 dB, so rimfire reports are easy to ignore (unless you’re shooting a .22 handgun, which creates a sharper, louder noise). For comparison, a 12-gauge shotgun generates 157 dB, a .30-30 rifle 158 dB, and a .357 magnum revolver emits a 164-dB blast that brings physical pain!

Firearms aren’t the only culprits when it comes to hearing damage. A power lawnmower generates 90 dB, while a snowmobile or chain saw emits 100 dB. Extended exposure to such sounds can also permanently damage hearing. I now wear inexpensive passive earmuffs whenever I mow my lawn.

I was first introduced to “ear protection” during Army basic training. The sergeant who taught us to shoot 1911 pistols advised plugging our ears with expended .45 ACP brass. This didn’t help much (it may have even amplified sounds), but alerted me to the hearing damage shooting big-bore pistols could cause.

Every shooter needs good hearing protection. Fire any kind of gun without wearing something to prevent high-decibel sounds from damaging your ear’s fragile cilia, and you’ll suffer a tiny bit of hearing loss. Every time you’re subjected to loud noises, a certain number of cilia tips break off. The damage, however slight, is permanent, cumulative and irreversible. Those cilia tips don’t repair themselves. Gunshot noise damage usually occurs a little at a time, and the effects aren’t immediately evident. However, it’s possible to shoot only once without ear protection and permanently damage your hearing. Diminished hearing or ringing in the ears (tinnitus) following a shooting session are both indications of hearing nerve damage.

Shooters today have five basic kinds of hearing protection available. These include soft disposable earplugs (dirt cheap, and they work very well), plugs with an external hearing circuit that hooks over the ear, custom-molded plugs with a built-in electronic circuit, plain shooter’s earmuffs (also relatively cheap), and electronic earmuffs that amplify normal sounds while blocking sharp impact noise. There’s a sixth option I’ll mention later.

While disposable earplugs and plain earmuffs are economical and highly effective, they muffle nearly all sound. You’ll preserve your hearing, but have a hard time deciphering range commands or simple conversation.

Commercial hearing protection devices are all assigned a noise reduction rating (NRR), which compares their relative efficiency in blocking out harmful noise. The ratings reflect the protection provided, measured in decibels. Each 6 dB increase represents a doubling of sound volume (loudness). Add another 6 dB, and the sound doubles again, which means 12 dB represents a 4x increase in volume. The higher the NRR, the better the protection offered.

Commercial hearing protection devices are all assigned a noise reduction rating (NRR), which compares their relative efficiency in blocking out harmful noise. The ratings reflect the protection provided, measured in decibels. Each 6 dB increase represents a doubling of sound volume (loudness). Add another 6 dB, and the sound doubles again, which means 12 dB represents a 4x increase in volume. The higher the NRR, the better the protection offered.

The highest-rated earplug on the market has a noise reduction rating of 33. The only way to get a higher rating is by using earmuffs in combination with earplugs. When both muffs and plugs are used, the combined NRR provides roughly 5 dB more than the higher-rated value of the two. For example, using NRR 29 earplugs along with NRR 27 muff-type protectors results in a combined NRR rating of 34 dB.

Polyurethane foam earplugs are the softest plugs available. They’re typically tapered, so they fit more comfortably in the ear. The maximum NRR rating for these plugs is 33 (be sure to check — some plugs have lower ratings). PVC foam plugs are stiffer than urethane plugs, so they’re easier to insert. They also stay in the ear more securely. These typically have an NRR rating between 29 and 33, and are available from several sources. Mack’s Shooter’s Putty (www.macksearplugs.com) differs from conventional shooter’s earplugs; they’re made of moldable silicone, and are pressed flat against the ear opening — not inserted into the ear canal. The NRR rating of these disposable, one-time-use plugs is 22 dB.

Passive earplugs offer excellent protection against high-impact noise from gunshots, but block out normal conversation. If hearing these sounds is important, a number of earplugs are available that include electronic circuitry that actually enhance your hearing. These work on roughly the same principle as hearing aids, but cost considerably less. Custom-molded plugs that contain this circuitry within the ear are popular with hunters. They’re unobtrusive and don’t cause the perspiration problems muff-type devices that surround the ear typically produce.

Companies like SportEAR, EAR Inc., and Electronic Shooters Protection produce high-quality plugs with electronic amplification that also block impact noise from gunfire. These are individually molded to the shooter’s ear, with costs ranging from $300 and up (sometimes way up). Nu Hear makes a universal-fit electronic plug that requires no cus- tom molding.

I’ve recently been using a pair of EarPro Sonic Defenders from SureFire. These soft, hypoallergenic polymer plugs fit unobtrusively in the ear. The earpiece is shaped like the concha — the large cavity of the external ear — with projections that fit the auditory canal. I’ve found these plugs more comfortable than regular earplugs, and are virtually invisible when worn. However, they must be properly seated to create an effective seal.

The earplugs feature something SureFire calls a Hocks Noise Brake filter, which allows you to hear routine sounds, but reduces noise levels above 80 decibels (dB). Permanent hearing damage begins at 85 dB or more. The earplugs have an NRR of just 9 dB (an attached “stopper” increases this to 16 dB when employed, but blocks conversation). According to SureFire, the attenuation rating increases as decibel levels go up. At 120 dB, Sonic Defenders supposedly reduce incoming noise by 39 dB. One great thing about these plugs is they retail for just $9.95 a pair.

The earplugs feature something SureFire calls a Hocks Noise Brake filter, which allows you to hear routine sounds, but reduces noise levels above 80 decibels (dB). Permanent hearing damage begins at 85 dB or more. The earplugs have an NRR of just 9 dB (an attached “stopper” increases this to 16 dB when employed, but blocks conversation). According to SureFire, the attenuation rating increases as decibel levels go up. At 120 dB, Sonic Defenders supposedly reduce incoming noise by 39 dB. One great thing about these plugs is they retail for just $9.95 a pair.

Both passive and electronic shooter’s earmuffs are offered by a variety of manufacturers, including Silencio, Howard Leight, and Pro-Ears by Ridgeline, Inc. Many of these are branded and marketed by companies like Smith & Wesson, Remington, Winchester, etc. Basic passive earmuffs can often be purchased for $20 or less and provide very good protection.

Electronic earmuffs are a real boon if you want to hear what’s going on as you prepare to shoot. Some have built-in directional microphones that can be cranked up to let you hear approaching game or eavesdrop on hunters conversing on a far hillside. When impact noise (i.e., gunshot reports) are detected, hearing protection kicks in. Electronic earmuffs typically range in price from $60 to $400, with many retailing for around $100. Some electronic muffs allow radio communication, but that’s a distraction I can do without.

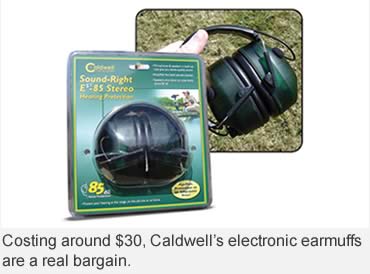

One of the best bargains I’ve found is Caldwell’s Sound Right ES-85 Stereo Earmuffs, which Battenfeld Technologies recently listed at less than $30. A minor annoyance is a discernable background hiss my muffs produce. Considering what these muffs cost me, I’ll happily put up with it.

When you shop for electronic earmuffs, pay attention to their shape. Some are bulky enough to interfere with proper gun mounting. The best shooter’s muffs have thin earcups specially designed to clear a buttstock when the gun is held to your cheek.

Another thing you may want to consider: Most muff-type protectors are held in place by an adjustable band that fits over the top of your head. If you like to wear cowboy hats (or any broad-brimmed hat), look for a model with a spring-loaded band that fits behind the neck. I’ve long used a Pro-Ears model with this arrangement, and am very happy with its performance.

While there’s a wide variety of both earplugs and protective earmuffs on the market, each style has its pros and cons. Regardless of their material and construction, earplugs are small and easily carried. They can be used in combination with muffs to provide the maximum in hearing protection. They’re also more comfortable to wear in hot, humid weather (an important consideration on June prairie dog shoots).

On the negative side, it’s more difficult to fit and insert earplugs than to simply place a muff-type protector on your head. Also, attempting to get multiple use from a set of earplugs can cause infection unless the plugs are specifically intended for reuse, carefully washed in warm, soapy water, and subsequently kept clean. Most plugs are so inexpensive it’s often better to simply throw them away after use. Finally, poorly fitting plugs may irritate the ear canal, and plugs are easy to misplace.

Earmuffs are designed so that one size fits most users. They can quickly be put on or removed, and they can be worn even if you have an ear infection. Too, they’re large enough that they’re harder to lose.

Disadvantages include additional weight and bulk. The muffs can become sweaty and uncomfortable when worn in hot weather. Finally, wearing eyeglasses can break the seal between earmuff and skin, reducing the muff’s effectiveness.

The sixth option I mentioned earlier requires no plugs or muffs. SRT Arms (www.srtarms.com) offers a selection of integral and screw-on suppressors for a variety of rimfire and centerfire firearms. These products are expensive ($375 to $980), and each requires a separate $200 federal license — provided suppressors are legal in your state (they aren’t in a dozen I can think of). There are also forms to fill out and your fingerprints taken. To be really effective, suppressed firearms should be used with subsonic ammunition, which can also be expensive (a box of subsonic .44 magnum fodder sells for $70). While this is an option, it’s neither practical nor readily affordable for most shooters.

Wearing hearing protection whenever you shoot is like buckling your seat belt when you drive. It makes sense and protects you from possibly serious problems down the road.

This article was published in the September 2008 edition of Buckmasters GunHunter Magazine. Subscribe today to have GunHunter delivered to your home.