Ever since humans first threw a stone to kill a bird, we’ve been searching for tools that can extend that range: slingshots, muzzleloaders, centerfires, rangefinders.

To facilitate extreme-range sniping, today’s hunter can use VLD bullets, multi-reticle scopes, laser rangefinders, calculators, angled cosine indicators and PDA computer programs. A trained shooter so equipped can reliably hit targets at ridiculous ranges — 500 to 1,000 yards.

There’s something satisfying about making a long shot, whether it’s 50 yards with an arrow or 600 yards with a rifle. I love the precision of a 1/4-MOA rifle, the magnified image through a 24x scope, the flat trajectory of a .550-BC bullet and the delayed whump of a long hit. There is a place and time for long-range precision, but more often than not, conditions conspire against it in the field.

Shooting long is effective and necessary for trimming varmint populations on farms and ranches. It’s also a wonderfully fun target-shooting game. Challenging your buddies to hit boulders, cow pies and dirt mounds at unknown distances is a hoot.

It’s also superb training for real-world hunting scenarios. It teaches you how to estimate range, use your optics and rangefinders, and calculate trajectory, wind drift and angled shooting variables. It also teaches you how to shoot accurately from field positions.

Becoming an effective long-range shooter requires detailed study of physics and math, plus extensive practice in ranging, scope adjustments, reticle use, shooting positions and trigger control. Many find it easiest to attend a long-range shooting school where you learn the difference between a mildot and a milradian, how to convert mils to MOAs, read wind, calculate wind deflection and much more. Most importantly, you get to shoot at steel plates at varying angles out to 800 yards with an instructor telling you what you’re doing wrong — and right. It’s fun and sobering. At Darrell Holland’s shooting school (www.hollandguns.com), I had little trouble hitting targets at 600 yards, but after that, hoo boy!

If you’re considering shooting beyond 400 yards at anything, the following will highlight what you’re up against.

Trajectory

Of all parameters affecting precise long-range shooting, this is the most easily controlled. Once you know the flight path your particular bullet takes, you can drop it on the right spot at any distance. Sort of.

The problem here is that no bullet perfectly matches the trajectories listed in ammo catalogs or handloading/reloading guides. Ballistic coefficients are often inflated by manufacturers. So are velocities.

Muzzle velocities can vary 30 to 200 fps from shot to shot, a huge difference at 700 yards. In addition, BCs change based on the rifle that’s firing the bullet. Scoring increases drag. So does coning motion, yaw and other flight characteristics that differ from rifle to rifle.

Before you presume anything about your rifle/ammo trajectory, you must test it extensively at all distances you expect to shoot. Don’t rely on ballistic charts or computer programs.

Range Estimation

Laser rangefinders have taken the guesswork out of measuring distance, but even the best units sometimes fail beyond 400 yards, and at that range, bullets start dropping like bowling balls. Ever try to laser a mule deer lying in grass across 500 yards of flat ground? Even an elk on a hillside at 700 yards can foil a laser rangefinder.

Taking readings from a “nearby, highly reflective object” like a boulder is fraught with error because at extreme range it’s impossible for human eyes to judge how close or far apart objects are. Misjudging the distance between your elk and a boulder by just 50 yards can result in a wound instead of a kill. A .300 Rem Ultra Mag firing a 180-grain Nosler Ballistic Tip (BC .507, MV 3,200 fps, sighted dead-on at 300 yards) puts the bullet minus 16 inches at 450 yards and minus 24 inches at 500 yards. That’s 8 inches of drop in just 50 yards.

Things get more critical at 600 yards, where the drop is 46 inches. At 625 yards, this increases to 52 inches, and at 650 yards, it’s a whopping 60 inches! I don’t think we can rely on laser readings of “nearby objects” to put our bullets right on the money. Using reticle subtension (bracketing with mil dots, hash lines, etc.) requires knowing the animal’s size, plus considerable practice.

Wind Deflection

This is the biggest fly in the long-range shooting ointment. Few of us understand wind deflection (bullets are not just drifting with the wind, but deflected by it onto a new course, which constantly changes over the duration of the bullet’s flight, depending on the fickle speed and direction of the breeze.) Guessing wind speed is as much art as it is science, and as such, it leaves a lot to be desired. Even if you employ a device like the Caldwell Wind Wizard, a digital anemometer, it only tells you the wind speed where you’re standing. Downrange, it could be gusting twice as hard, blasting up or down a canyon, changing direction, who knows? On a mountain in Canada, I once watched snowflakes simultaneously blowing right, left, up and down over a few hundred yards.

For serious long-range shooting, you have to use an anemometer, and you must train long and hard to interpret downrange wind changes. It’s an art, and it’s never guaranteed.

In a right-angle 10-mph breeze, the 180-grain bullet mentioned previously will drift 22 inches at 600 yards; 26 inches at 650 yards. At 15 mph, the deflection increases to 33 and 40 inches. In other words, even if you nail the range estimation, if you misjudge the wind by 5 mph, your shot misses point of aim by 11 inches at 600 yards.

Can you say “gut shot?”

Angle

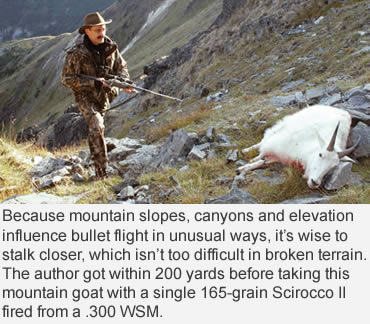

Shooting up or down at steep angles changes bullet impact because the projectile is not traveling at 90 degrees to the gravity’s pull. The critter may be 500 yards out, but gravity may be pulling at a 50-degree angle. The difference can be calculated if you know the precise angle and the cosine. For instance, the cosine for a 60-degree angle is .500. For a 600-yard shot, multiply 600 by .500, and you get 300 yards. That’s the corrected distance. Your bullet trajectory will be the same as if you were shooting over a 300-yard horizontal distance.

Alas, every angle has a different cosine (30 degrees is .866, 45 degrees is .707), so you have to memorize a lot of cosines, then multiply under pressure. But first you must know the range and angle. Quick, what’s 537 yards times .707? Serious shooters carry a pocket calculator for this, plus a protractor. The Mildot Master (www.mildot.com) includes a simple weighted plumb line and angled “rule” along the edge of the card. Aim the card at the target and note the angle indicated. A slide rule on the card shows the effective target range. The device includes another slide rule for calculating the target distance in conjunction with mildot reticles as range estimators.

he Angled Cosine Indicator mounts to your scope and shows the degree of angle plus its cosine. It’s made by Sniper Tools Design Co., (800) 651-1050, www.snipertools.com.

Leupold and Bushnell rangefinders automatically calculate angled ranges, but they are subject to the same environmental limitations as standard laser rangefinders. Shooting up or downhill at long range takes serious study and practice.

Elevation, Temperature, Moisture

The height above sea level changes trajectory because air density decreases, bullets drag less and strike higher. This doesn’t amount to an inch or two at 400 yards, but added to other complicating factors such as imprecise range estimation, unknown shooting angles, etc., it can throw a monkey wrench into long-range shooting.

Temperature changes bullet impact by influencing the efficiency of powder. The colder some powders get, the less velocity they generate. Cooler temperatures and humidity make air denser, and bullets drop even more.

Mirage

What do you do when heat waves make your target seem to move? This is a real stumbling block to accurate aiming. Mirage results from hot air rising. Various density levels of that air act as lenses, making distant images contort, shimmer and seem to move. Are you aiming at the actual target or a contorted image of it?

Terminal Performance

Most shooters realize no bullet can do it all. Extremely soft projectiles mushroom nicely at low impact velocities, but pancake or break apart at high speeds. Tougher “premium” bullets stay in one piece and mushroom reasonably at high impact velocities, but may not expand at low speeds.

This suggests that one can tailor his ammunition to each hunt. Trouble is, you can’t guarantee at which distance you’ll get your shot. Load a fairly soft bullet for guaranteed expansion at 500 yards, and what do you do when an elk steps out at 80 yards? Ask him to wait while you back up? An all-around bullet like the Barnes Triple Shock X or Winchester’s XP3 can alleviate most of this concern, but what if those don’t shoot well in your rifle?

Accuracy

It’s a myth that magnum cartridges are not inherently accurate. Well-built super magnums shoot as precisely as 6mms. So the biggest .300 magnums can group small at extreme ranges — if the shooter doesn’t flinch.

There’s the rub. We like super-mag performance, but hate the recoil. This leads to inadequate practice and flinching. The good news is super mags aren’t mandatory. To illustrate that point, master gun builder Darrell Holland says, “I’ve done hundreds of post-mortems on game, and not one of the animals guessed within 200 fps the muzzle velocity of the bullet that killed it.”

Fetch!

A big concern with any far-off shot is recovery. Wound a buck at 100 yards, and a second shot can finish it. But at 800 yards? In some mountains, a wounded bull could heal and father offspring before you could climb to it.

Some extreme-range shooters have killed elk across a big canyon — then failed to find them. “Everything looked different when we finally got there!” explained one shooter.

There are more complicating factors to consider, but here’s the bottom line: There are too many variables to make this a commonly accepted practice among big game hunters.

Does this mean you should never practice long-range shooting? Hardly. Tune your rifle and practice shooting long. The more you study, practice and learn, the better shooter you’ll become. Someday, you may need to finish off a wounded animal at 600 yards. Meanwhile, hitting steel plates or desert boulders at extreme ranges is great fun in itself, sufficient reason to build a long-range sniping rig. There’s always a rancher who needs help trimming overpopulated rodents, many of which must be targeted at extreme range. Once you’ve learned to shoot precisely past 500, that next deer at 350 yards will be a slam dunk.

So learn to shoot long. Practice and become proficient. But don’t substitute it for genuine hunting skills. As many a professional guide has advised over the years, “Get close. Then get closer.”

This article was published in the July 2007 edition of Buckmasters GunHunter Magazine. Subscribe today to have GunHunter delivered to your home.