Although retired for almost 30 years, this classic lever action remains one of the best deer guns of all time.

A few springs ago, my wife and I walked into a sporting goods store intending to buy some fishing hooks. I walked out with a Savage Model 99 rifle.

“How did that work?” my wife asked.

“Just the way I’ve been hoping the last 30 years.”

I’d been looking for an older Savage Model 99 in .300 Savage. I wanted it for its good looks, fast handling in the deer woods and to revisit the days of my youth when I carried a Savage 99 on hunts for mule deer.

The Model 99 traces its beginning back to 1895 when Arthur Savage developed his Model 1895 lever action chambered in .30-40 Krag and .303 Savage. The 1895’s solid breech was plenty strong enough to handle new smokeless powder loads. Its most noticeable feature was a rotary magazine that cycled cartridges smoothly and reliably. A bit bulky and heavy, the gun didn’t set any sales records. Only about 5,000 were manufactured.

Savage started revising the rifle and called the finished product the Model 1899. It had a slimmed-down receiver, a magazine capacity reduced to five rounds and the addition of a cocking indicator and retracting firing pin. The new gun’s buttstock flowed forward into the receiver to give the gun a continuous and lissome profile that cumulated in a slender forearm. Chamberings included .25-35 Win, .30-30 Win, .303 Savage, .38-55 and .32-40. Round, full-length-octagon and half-octagon barrels in 22- or 26-inch lengths were available. Military muskets with 28- or 30-inch barrels were also sold. The 1899 immediately became a good seller.

The rifle became legendary for its smooth cycling. Opening the lever only a slight amount dropped the bolt out of lockup, and all the remaining force went toward extracting and ejecting the spent case. Pulling the lever closed cocked the firing pin and stripped a cartridge out of the magazine. The rotary magazine rotated so smoothly, presenting a cartridge in line with the bolt and the chamber, next to no force was required to push the cartridge from the magazine and into the chamber.

A nice touch to the rotary magazine was a cartridge counter that showed the number of rounds in the magazine through a window in the left front of the receiver wall.

The moment a cartridge starts out of the magazine, the 99’s extractor latches onto the case rim and removes any chance of the action jamming due to double-feeding cartridges. This controlled-round-feeding feature is rarely mentioned. Yet it is highly touted as an important feature of reliability on bolt-action Mauser 98s and Winchester Model 70s.

One supposed advantage of the 99’s rotary magazine was that it allowed using pointed bullets that could not be safely used in rifles with tubular magazines. But back then, and up into the 1960s, very few, if any, pointed bullets were available or used by hunters. So the fact that pointed bullets could be used in an 1899 and not other lever actions like Winchesters and Marlins was a moot point.

The Cartridges

The Cartridges

The Savage Model 99 (about 1920, the model number was abbreviated) was the rifle that introduced several high-pressure cartridges. It was also offered in a variety of other modern calibers.

In 1912, the 99 was chambered in .22 Hi-Power Savage that was essentially a .30-30 case necked down to hold a 70-grain .228-inch-diameter bullet with a muzzle velocity of 2,800 fps. That was pretty hot stuff back then. In 1914, the .250-3000 Savage was introduced. The 3000 came from the cartridge’s 87-grain bullet at that velocity. To this day, the .250-3000 retains a cult following as one of the best deer cartridges ever developed.

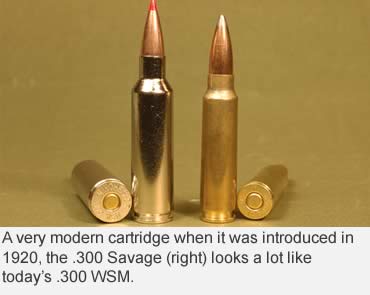

In 1920, the .300 Savage was introduced as a short cartridge that would fit in the 99’s action, yet produce nearly the same velocity with a 150-grain bullet as the .30-06. It came up a bit short of the .30-06, but it was close enough, and in a compact rifle like the 99, it was an immediate hit with big game hunters. The .300 case had a sharp shoulder and a short neck to maximize powder capacity. In fact, it looks like a narrow version of today’s cutting-edge development in cartridge design, the .300 Winchester Short Magnum.

When I was a kid, I occasionally hunted with three men and their father who hunted elk with 99s in .300 Savage. Their rifles had open sights, and they had no problem killing elk at the 60 to 80 yards they shot. They were so content with their .300s that when I showed up one day with a scoped 7mm magnum, they wondered aloud what advantage my heavy and cumbersome rifle had over their handy 99s.

In the following years, the 99 was chambered for cartridges that operated at even higher pressures. They included the .243 Win, 7mm-08 Rem, .284 Win, .308 Win and .358 Win. The .375 Win was also chambered to compete with Winchester’s Big Bore Model 94 lever action in the same caliber.

A whole book would be required to describe the different models of 99s produced over the years. Suffice it to say Pre-World War II patterns include the A, B, E, EG, F, G, H, K, R, RS and T. Post-1945 patterns include the A, C, CD, DE, DL, E, EG, F, PE, R, RS and 358. A number of deluxe models were also made with custom wood, sights and engraving, and gold and silver inlays, were also made. They include the CD, BC, AB.

The reason 99s operate so smoothly is each rifle required a lot of hand fitting. That amount of labor, though, made the 99 increasingly expensive to produce. Shortcuts were taken to keep prices in check, like replacing the rotary magazine with a detachable magazine. However, quality suffered, and the various models were dropped until, in 1989, only the Model 99C remained.

All sorts of conflicting reports exist on the last year 99s were made. One source states 1985 or ’86, another 1989 and yet another late 1990s. There was a Model 99 Centennial Edition made in Spain in the mid ’90s, but it doesn’t count.

When a rifle is no longer produced, it quickly assumes the position of a collectable. Prices go up accordingly. Prices have increased significantly on 99s made up to the 1950s, and those in calibers that were not so popular at the time. A friend recently sold a 99 chambered in .358 Win for $1,650.

My 99

My rifle is a Savage 99F made in 1955. Its 20-inch barrel is chambered in .300 Savage. The gun was in good shape when I bought it, with only some of the bluing on the bottom of the receiver worn from some hunter carrying it there on its balance point. The stock smelled like it had spent many years in a backwoods cabin near a wood stove. The rifle still had its factory-installed Marble’s aperture rear sight that extends back over the grip on a piece mounted on the top rear of the receiver.

I started shooting the rifle with 150-grain jacketed bullets. With the Marble’s sight, it was no great feat to punch 2-inch groups at 100 yards. However, I soon started shooting 150-grain cast bullets at 1,700 fps for practice loads, and the aperture sight didn’t have enough vertical adjustment to get those slower bullets to hit at the point of aim at 100 yards. So I searched around for a scope about the same age as the rifle. I found an old Lyman All-American 4 power with a vertical post and horizontal crosshair reticle. The scope has a bright view. Each click of its reticle adjustment moves the bullet impact about 1 inch at 100 yards. The adjustments do track reliably, going back and forth from the settings for cast-bullet practice loads to hunting loads. With a leather sling, the rifle weighs 7 3/4 pounds.

I wanted to take my 99 after mule deer like I’d done with a borrowed Savage 99 when I was a boy. But whitetail numbers around home have increased so dramatically in the decades since that it is much easier, and requires less gas for the pickup, to find a whitetail.

With a white-tailed buck and doe tags in hand, I headed out. I hunted ridgetop thickets of lodgepole pine and bottom swamps of brush and quaking aspen. I saw quite a few does and a couple of small bucks during the day. I practiced getting the rifle quickly on the deer as if they were big bucks and I was going to shoot. There really wasn’t anything to it. As I kept my eye on the deer, the rifle came up and the comb met my cheek, the scope lined up with my eye, and the post reticle was on the deer.

Just after sundown, I told myself to shoot the next big lone doe that came along. Right on schedule, a doe walked through the trees and stopped broadside at 80 yards. I brought the 99 up and shot. The deer took off on a mad dash. Nearly on its own, the rifle went “click, slick” and chambered another cartridge. There was no need, though, because the doe fell after 30 yards.

My son thought that was pretty neat, so he took the rifle the next week. He stalked to within 40 yards of a feeding doe and was just about to shoot when it took off up the ridge. The deer passed an opening and my son fired. The deer fell over dead.

Loads for the .300

One nice thing about the .300 Savage is that it doesn’t require an expensive controlled-expanding bullet to perform well on big game. With a mild velocity of 2,700 fps, a regular 150-grain soft point Hornady, Sierra or Speer bullet will expand well, yet hold together. The .300 Savage load we used on those deer was a Remington 150-grain Pointed Soft Point Core-Lokt with 43.8 grains of Varget powder for a muzzle velocity of 2,740 fps. The bullets expanded, did their work inside the deer and exited.

Federal, Remington and Winchester still make .300 Savage ammunition. All three load their standard soft-nose 150-grain bullets with a stated muzzle velocity of 2,630 fps. From the 20-inch barrel of my Savage 99, the Remington 150-grain load clocked 2,535 fps. Federal and Remington also load 180-grain soft-nose bullets at 2,350 fps. At 300 yards, the 150-grain loads retain about 1,100 foot-pounds of energy, and the 180-grain bullets have 860 foot-pounds of energy. Those loads should handle about any big game out to 300 yards, which, in spite of all the mega magnums out there today, is still a long shot.

Handloading does make the .300 more versatile. For small game like coyotes, a light bullet such as the Speer 125-grain TNT at 2,800 fps provides a flat trajectory for long shots. A 150-grain bullet at 2,700 fps is pretty hard to beat for an all-around deer load. For game larger than whitetails, you might want to move up to a heavier 165- or 180-grain bullet. A 200-grain bullet at nearly 2,400 fps would take any moose that ever walked. As the load sidebar shows, my old 99 shot just as well as many of today’s high-dollar bolt-actions.

The End

Depending on who you listen to, production of the Savage 99 stopped somewhere between 1997 and 2002. There is a rumor floating around that Savage Arms is considering bringing back the Savage 99. For now, though, there are quite a few used 99s on the racks of many sporting good stores, and a hunter looking for a Savage 99 should have no problem finding a decent one.

That’s how I got my Savage 99, and I’m completely happy with it.

Read Recent GunHunter Articles:

• Five Guns Worth Finding: These hunting guns are no longer made, but are well worth seeking on the used gun market.

• Stock Options: Got an inaccurate rifle? Maybe it’s time for a different handle.

This article was first printed in the October 2008 edition of Buckmasters GunHunter Magazine. Subscribe today to have GunHunter delivered to your home.