By Jon R. Sundra

Ever been at a shooting range prior to the season opener and overhear someone say, as they’re looking at a retrieved target, “That’s good enough for hunting” or “More than minute of deer”?

Those and similar comments suggesting pinpoint accuracy isn’t really needed for hunting are voiced at shooting ranges across the country. Such a scenario might have a hunter holding a target with several random holes forming a 3-inch group fired at 50 yards and proclaiming that’s all the accuracy he needs.

I suppose if you pretty much know you’ll never be faced with a shot beyond 50 yards, that kind of accuracy would indeed be “good enough.” And there definitely are circumstances where you can be fairly certain you’ll never have to take a long shot.

“Hunting accuracy” to some people denotes not what the gun is capable of, but rather how well the guy behind it can shoot under hunting conditions. If that’s the case, then yes, there is such a thing as hunting accuracy, but it’s a far cry from the theoretical capabilities of a rifle fired from a bench.

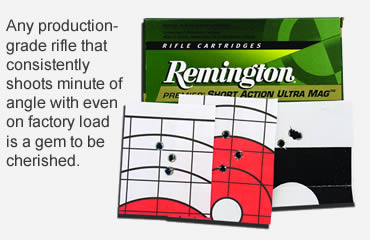

Let us assume we have a true minute of angle rifle, one that’s capable of consistent 1-inch groups at 100 yards under ideal conditions. Before proceeding, however, let me tell you how rare it is to have a genuine MOA hunting rifle shooting factory ammunition. To hear some writers tell it, if a rifle doesn’t shoot under an inch at 100 yards, it’s a turkey and should be sold forthwith. Truth is, a sporter-weight hunting rifle chambered for any cartridge larger than, say, .257 Roberts, that consistently shoots an inch or less with even one factory load, is a gem to be treasured.

Handloads? That’s another matter. Any rifle that’s been tuned, properly bedded and for which one has done the necessary handload development, one has a right to expect MOA accuracy or very close to it. My personal standard is 1 1/4 inches, and if I can get that, I’m ecstatic. And again, I’m talking consistent accuracy — three-shot group after three-shot group — into 1 1/4 inches or less from a cold barrel.

It is said that the average hunter would be hard-pressed to put three out of three shots into an 8-inch pie plate at 100 yards from the standing offhand position. Based on my experience, I have to agree with that assessment. And that’s assuming our subject is perfectly relaxed and shooting at a paper target. Put an animal, much less a trophy animal, into the equation, and suddenly that calm pulse and breathing is out the window.

Add to that excitement of having a critter in your scope, the effects of having run or climbed to get into shooting position, and you’d be lucky to hit a Buick at 100 yards offhand . . . at least for a minute or two or however long it takes to catch your breath. That’s why I always tell my guide at the start of a hunt that as long as I’m the guy with the gun, nothing is going to happen until I get there. There’s little sense in him always staying 100 yards ahead of me as I huff and puff to keep up, then have him frantically wave for me to catch up and take a shot the moment I get there. I’m about to have a heart attack as I gasp for air, and he wants me to immediately take a 350-yard shot across a valley? Yeah, right!

Anyway, getting back to our theoretical MOA rifle, that means with a dead-steady rest, no shot will be more than a half-inch off in any direction. Extend that to 400 yards and our bullet still isn’t straying more than 2 inches in any direction from our expected point of impact. You gotta’ admit that a 4-inch group at 400 yards is pretty phenomenal, especially when you consider the vital zone of a whitetail is about a 10-inch circle. Even at 500 yards, our groups would be half that size and comfortably in the vital zone!

But now let’s put the above scenario in a real-world context. Let’s assume a better-than-average shooter who, from the offhand position, can punch 4- to 5-inch groups at 100 yards with fair consistency with a minute of angle rifle.

That means that 1 inch of that group is the result of the normal dispersion of an MOA rifle; the rest is marksmanship or lack thereof. Again, we’re assuming our shooter is rested, as one would be having been on-stand for a while, with normal pulse and breathing.

Now, is there a hunter out there who doesn’t experience a a sudden increase in heartbeat and breathing when game enters the picture? And I’m talking just a legal buck. Put a trophy buck in the picture, or just the best buck this guy’s ever seen through a scope, and the excitement level climbs yet another notch.

Taking in to account what excitement alone does to our pulse and breathing, and those 4- to 5-inch groups literally double in size.

If you think I’m exaggerating, try the following experiment: With a 100-yard target set up at the shooting range and your rifle on a bench, sprint 100 yards and back, then immediately pick up your rifle and fire a three-shot group. If you can keep those shots inside a 10-inch circle, you’re a better man than I am, Charlie Brown!

This brings to mind a hog hunt I made a few years back. I had misjudged the range on a feral hog and hit him too low in the shoulder. He couldn’t run very well, so I was able to catch up to him, but to do so took a good bit of exertion. I was panting like the Little Train That Could.

The pig was no more than 60 yards away when I got my first chance to finish him but I couldn’t keep the reticle on him to save my life. At the shot, he took off again, with me in pursuit. To make a long story short, I missed three different opportunities to put that hog down for keeps, all at distances well under 100 yards.

Shooting at game offhand with an MOA rifle becomes very iffy for most of us if the distance is even approaching 100 yards. This points to how important it is to employ a rest of some sort to steady the gun, because anything is better than shooting offhand. The problem is that so many situations negate the much steadier kneeling, sitting and prone shooting positions because of brush and other ground obstructions that obscure the line of sight.

With a limb, rock or tree on or against which we can get a one-point support for the forearm while in the standing position, the 10-inch group we would otherwise get should be cut by more than half.

From the kneeling or sitting positions with the aid of shooting sticks, our above-average shooter with his MOA rifle should be able to get groups down to around 2 to 2 1/2 inches.

The steadiest shooting position is prone, which in conjunction with a second support under the butt of the rifle, can allow you to almost match the steadiness of a shooting bench with sandbags, providing your pulse and breathing are at least somewhat relaxed. Other factors involved are knowing the range, the point of impact at that range and doping the wind correctly.

The points I’m trying to make are: 1) you’re never shooting at game without a certain degree of accelerated breathing and pulse rate, regardless of how steady the shooting platform; 2) there’s always pressure to hurry the shot because game animals are likely to bolt at any given moment; 3) shooting at distant game offhand is never a good idea; and 4) you can never have too accurate a rifle, because the normal shot dispersion must always be added to all the other factors that affect shot placement.

Each of us must determine what shots we will or won’t attempt, but I’m reluctant to pull the trigger unless I’ve got a steady enough hold that I can keep the reticle pretty close to where I want it. If that crosshair is wandering on and off the animal, I rarely take the shot. I respect the animals I hunt too much for that.

The bottom line is, you can never have too accurate a rifle. If 2 MOA is good, 1 MOA is better, because all other things equal, with or without the human element, our chances of putting that all-important first shot into an animal’s vital zone are better. To put it another way, when it comes to hunting accuracy, you want all you can get!

This article was published in the July 2007 edition of Buckmasters GunHunter Magazine. Subscribe today to have GunHunter delivered to your home.