Understanding whitetail breeding is the key to hunting the rut effectively.

In the small woodlot behind a lush clover field, a buck stirs in his bed. The sun set less than an hour ago. He rises, surveys his surroundings and takes two steps forward. He licks his nose and tests the air while his ears twist this way and that, straining against the cloud of mosquitoes swarming around his head for any out-of-place sound.

Seemingly content that all is well, he twitches his tail and moves slowly down the trail, the same one he’s used for days, perhaps even weeks, moving from the security of his bailiwick to the open field, where he’s fed every evening under the cover of darkness. Each day seems the same as the last, but each is a minute shorter than the previous one.

Along the trail, he approaches the same clump of alder saplings he has passed the last four days. For the last two, he paused and stared at it momentarily before continuing. This time he turns, approaches it and lowers his head.

There’s no comprehension of his actions. Following directions hard-wired into his DNA eons ago, he plunges the antlers he’s guarded so carefully over the past several months into the wood and begins rubbing vigorously. As he does, soft brown velvet dangles, then falls off in shreds, exposing blood-stained bone.

While it’s not here yet, the buck has taken his first significant step toward the remarkable annual phenomenon we call the rut.

WHAT IS IT?

The rut.

The mere mention of the word quickens the pulse and stirs thrilling images in the mind of every deer hunter. It is that magical time when the woods come alive with action, and wily mature bucks drop their guard, exposing themselves to daylight dangers.

Deer hunters savor it. The more dedicated ones study it tirelessly because they know a better understanding of their quarry provides better insight into how to hunt it more effectively.

To better understand it, we first need to define exactly what it is. We also need to clear up some of the misunderstandings and misconceptions that have been perpetuated for generations.

The first area needing clarification is what is meant by the term rut. The rut is the mating season of ruminant mammals, alternately referred to as the roar in red deer and tupping in sheep.

It includes not just breeding but the entire process leading up to breeding, including the physiological changes and physical behaviors associated with preparation and courtship. For white-tailed deer, the rut can last up to three months.

The definition becomes even more confusing when we try to define peak rut.

Several years ago, I contacted deer biologists from all of the whitetail states to ask about peak rut dates. Several offered cautionary words on defining it, but New Brunswick deer biologist Rod Cumberland summed it up best when he stressed there is a distinction between peak rut and peak breeding. “I see these terms used interchangeably,” he said, “and in a hunter’s mind they tend to lump it all together as the rut. However, biologically and behaviorally, they are really distinct times.”

Biologists are primarily concerned with peak breeding. But as mentioned, the rut is the process involving all behavior associated with breeding, including preparation, searching, chasing, fighting for breeding rights and breeding. By definition, peak rut is when these activities peak, which is typically a week or more before peak breeding. The latter, a period when the majority of older bucks and receptive does have paired up and melted off into some secluded area, can actually be a bit of a letdown from peak rut, especially for the hunter.

TRIGGERS

Getting to peak rut is a long process, so let’s back up and look at how it all comes to be in the first place.

The primary trigger to rutting behavior is photoperiodism. A decline in the amount of daylight causes physiological changes in both male and female deer. Observable effects take longer in females.

The first overt sign in males, caused by an increase in testosterone, is cessation of blood supply to the antlers. Velvet dies and peels off.

Whether it’s deliberate or not, a buck will rub the velvet off on vegetation and will continue rubbing his bare antlers throughout the fall.

With a sudden surge in testosterone, he’s becoming more aggressive, and rubbing helps strengthen the neck and shoulder muscles he’ll need when sparring and fighting other bucks for breeding rights.

Bucks also rub as a dominance display, or to vent built-up aggression. These early season rubs often have limited value to hunters.

Over time, though, rubbing becomes more routine. A buck or several bucks rub the same tree on a regular basis. In addition to shaping up, they’re also leaving olfactory messages. These signpost rubs indicate at least some kind of regular travel pattern and can be useful for hunters.

The next sign the rut has begun is the breakup of bachelor groups. Until now, bucks have been traveling in loose, male-only aggregations. They might bed and travel together, but they can almost always be found feeding as a group, even though the group composition will vary from day to day or even hour to hour.

As fall approaches, interaction increases and shifts from social grooming to meshing of antlers and casual shoving and jousting matches. Eventually, the sparring becomes more serious. Bucks test each other and gradually establish a social hierarchy. They also become less tolerant of one another’s company, although the sound of rattling antlers will bring them back together.

SECONDARY TRIGGERS

SECONDARY TRIGGERS

On the doe side of the equation, natural selection has honed timing of the rut over eons, particularly in northern climates.

Fawns must be born late enough to benefit from spring green-up, but early enough to achieve sufficient growth to survive the rigors of winter.

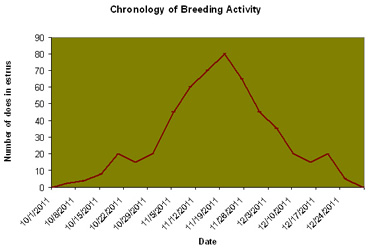

If you graph when does come into estrus, it appears as a bell curve rather than a bar. A majority of does breed within a narrow window of time, with the number of receptive does steadily declining before and after the peak period.

If you refine it further, instead of a steady decline on either side of the peak, there are two lesser peaks (one on either side). Does not bred during the first peak, and in some populations a few doe fawns, will come into estrus roughly 28 days after peak breeding. A few will enter estrus approximately 28 days beforehand.

While the bucks have been slowly increasing their rut-related activity like runners stretching and warming up for a race, the first whiff of pheromones from an estrous doe is like a starting gun. The race is on, and the first breeding behavior is like a sprint — a brief flurry of excited activity. The marathon is yet to come.

If they haven’t already done so, this also prompts bucks to begin making scrapes. Like rubs, there are different types. Some are opened once and never visited again. Others are occasionally re-visited, and some will be visited regularly over the next few weeks.

The key for the hunter is to pick the latter. One thing they have in common is an overhanging licking branch on which bucks and does deposit additional scent messages.

Another trait of key hunting scrapes is they’re found in the same place as in past hunting seasons. In fact, whitetails might actually use them year round, but to a much lesser degree outside the rut. If you notice scrapes in the same place every year, chances are they’ll be visited on a regular basis during the rut.

We don’t know exactly why bucks make scrapes, but they appear to serve some function in scent communication, which is as sophisticated and complex to a deer as vocal communication is to humans.

To put it another way, a deer’s olfactory system is sensitive enough that with one whiff of fresh urine, they can probably tell the sex and individual identity, and quite possibly the fitness, social rank and breeding status of the deer that deposited it.

PHASES or STAGES

The dust has barely settled on the first (and lesser) breeding period when bucks begin to ramp up rut behavior. And they do so in varying ways and intensity.

They’ll spend increasingly more time in search of receptive does, a behavior we call the seeking phase.

As a doe reaches or nears estrus, she becomes increasingly more attractive to the opposite sex. Once they find her, bucks enter the chase phase and will pursue her until she finally relents.

It’s human nature to try to organize things into neat categories, but that doesn’t often work in nature. Categorizing the different aspects of the whitetail rut can be helpful, but it also has created a good bit of confusion.

The phases most certainly exist, but it’s more accurate to apply them to individual animals at a particular time rather than the whole group.

I hunt a 1,500-acre Alabama parcel every year. Because I want to make the most of the long trip from Maine to Alabama, I try to time the hunt as close to peak rut as possible.

Even so, at the end of each day when the hunters converge at the skinning shed to swap stories, it’s not unusual to hear one guy observed several bucks chasing a doe, while another observed a few bucks cruising travel corridors and scent-checking food plots. A third might have watched bucks and does casually feeding side by side in a food plot.

While deer often are in different phases, it’s fair to say seeking and chasing increases as the number of estrous does increases. And if the peak of this activity lines up with favorable weather, you could be in for an exciting few days.

This leads to perhaps the greatest misconception about the rut.

Two years ago, I produced a rut chart for Buckmasters based on data collected from state biologists. Specific dates varied from state to state and between regions within particular states, but every biologist I contacted concurred on one point: Peak breeding (and, therefore, peak rut) occurs at roughly the same time every year, regardless of weather, temperature, hunting pressure, moon phase or position. If it’s too warm, it just happens more at night and we don’t see it.

LOCKDOWN

Peak rut, the time when a majority of does are in estrus, doesn’t last long. Bucks will chase a hot doe in earnest and battle, sometimes to the death, over the right to breed her. Eventually she gives in and stands for one of her suitors.

Before she does, however, the pair might slip off to a secluded area. We don’t know whether it’s intentional or merely a result of avoiding competition and interference.

And because so many does are at or near receptivity at the same time, the level of deer activity sometimes seems to disappear. That’s why this period is sometime referred to as the lockdown.

While the peak of whitetail breeding is occurring, the peak of visible breeding behavior is over for hunters, at least until the brief and lesser chasing that goes on just before the second rut.

With the days getting shorter, the temperatures colder and the important work out of the way, a deer’s attention now turns to building up stores of fat for the impending winter.

CONCLUSION

If you think you’ve got it all figured out, guess again. The best hunters understand that greater knowledge only leads to more questions.

We also need to remember that deer, like humans, have individual personalities. They don’t read books or magazine articles that tell them what they should be doing during a particular moon phase or a certain week of the calendar.

Whitetails are motivated by eons of evolution and natural selection designed to give them the greatest chance of passing on their genetic material. And Mother Nature is always experimenting.

Read Recent Articles:

• Covert Ops: How to get more from your trail cameras than just pictures.

• Management Makeover: Biologists face new challenges as herd dynamics change.

• The Deer Doctors: New studies examine predator impact, protein effect and more.

This article was published in the September 2013 edition of Buckmasters Whitetail Magazine. Subscribe today to have Buckmasters delivered to your home.