What is it about these remarkable works of natural art that so fascinates us?

Humans have long been fascinated by antlers. The ancients depicted large-racked bucks on cave wall drawings, and Native Americans often sought out the biggest bucks, adorning themselves and their lodges with antlers during ceremonial events.

To this day, the mere sighting of a big-racked buck starts the heart racing. Modern hunters seek them, and management programs are directed toward increasing the number and improving the quality of antlered deer.

What is it about them that so fascinates us?

I’m not sure, but like millions of others, I am drawn to big racks like a moth to the flame.

ANTLER ANATOMY

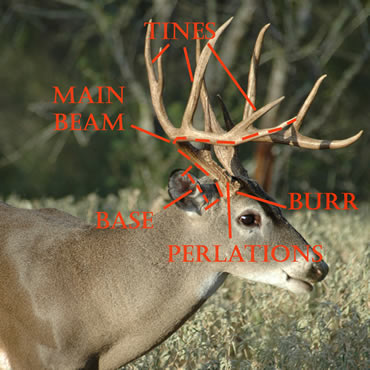

Whitetail bucks normally sport two antlers, collectively referred to as a rack. The anatomy of a common rack can be broken down into several parts. We’ll start at the bottom, and work our way up and out.

Each antler attaches to the skull at a permanent protrusion of bone called a pedicle.

Just above this is a knobby, flared ring called a burr. The main stem or trunk of the antler that originates at the burr and extends out to the tip is called the main beam.

The first few inches of the main beams, just above the burr, are called the bases. Texture of the bases varies from smooth to roughly textured with knobby projections called perlations.

Several points or tines grow upward, roughly perpendicular to the main beam, usually in a somewhat uniform fashion. A typical rack (so called because it is the general rule rather than the exception) exhibits bilateral symmetry — each side being more or less a mirror image of the other.

The first point is properly referred to as the brow tine, but sometimes is attributed more colorful names like eye guard. Antler scorers once referred to this as a bez (pronounced bay), but this term has largely gone out of use, except for caribou, and has been replaced with the less colorful terms P-1 (for Buckmasters Trophy Records) or G-1 (for Boone & Crockett and Pope & Young scoring).

The next tine, once referred to as the tres (tray), is now simply the P-2 or G-2. Successive points are numbered accordingly. The terminal tip of each main beam is also considered a point. Thus, a whitetail with matching antlers, each having a brow tine and two more vertical tines on each side would be called an 8-point buck. Westerners sometimes call this a 4-point. They’re wrong.

All tines are points, but not all points are tines. Abnormal points are any protrusions that vary from a typical, symmetrical configuration. Those descending off the main beam are called drop tines. Other major projections growing off the main beam in a non-typical or asymmetrical fashion may be referred to as points or tines. Those originating from other tines rather than the main beam are called kickers, and those sprouting from the bases are stickers.

Irregular or non-typical racks are those with several abnormal points. The BTR defines them as having enough irregular inches to comprise 10 percent or more of the rack’s total score.

ANTLEROGENESIS

Perhaps the best way to explain what antlers are is to describe how they come to be, through a process called antlerogenesis.

Antler growth begins early in a deer’s life. Just a few months into his first spring, a young buck’s antlers begin growing from the already-formed pedicles on his forehead. We don’t see them because they’re hidden beneath the skin. But by his first autumn, the young male’s forehead will be adorned with leathery buttons. Occasionally, buck fawns might even sport tiny spikes or bony protuberances scarcely more than an inch or two long.

It is not until his second spring that a buck’s antler growth really begins. Changes in amount of daylight prompt the pituitary gland to produce growth hormones. That triggers the release of insulin-like growth factor (IGF), which ultimately stimulates antler growth. The process starts slowly but increases as the days grow longer.

During this time, antlers are living, growing tissue. In fact, they’re among the fastest-growing forms of tissue, capable of growing up to an inch a day during peak periods. Outside, they’re covered with hairy skin, called velvet. Inside, they’re made up of cartilage, nerve tissue and thousands of blood vessels. Traces of the antler’s circulatory system can sometimes be seen in the hardened antlers in the form of shallow, branching grooves, called bloodlines.

As antlers reach their maximum size, photoperiodism again plays a role, as shorter days stimulate the pituitary gland to increase testosterone secretion. This triggers a process called mineralization.

Soft antler tissue is converted to bone when minerals are deposited within the matrix of cartilage and blood vessels. Once the process is complete, blood supply to the antler ceases. The antlers and their velvet covering die. Velvet sloughs off completely within about 12 hours, leaving the dead bone of the completed rack behind.

Like leaves on an oak tree, antlers are cast off and then regrown every year. Once the rut is over, their purpose has been served, and retaining them wastes valuable energy. Again, waning daylight signals physiological changes. The buck begins drawing minerals back into the body, leaving antlers more brittle and porous. Eventually, a specialized layer of cells forms between the pedicle and the base, degrading the point of attachment until the antlers fall off.

NON-TYPICALS

The two major causes of non-injury induced irregular antlers are genetics and age, both interrelated to a degree.

According to Kip Adams of the Quality Deer Management Association, some research suggests that upward of 50 percent of the deer in wild populations have the genetic makeup for abnormalities.

We don’t see them as much because most deer don’t live long enough to express them.

Common abnormalities include sticker points, drop or forked tines and webbed or palmated beams. However, more radical examples sometimes occur. Main beams can split, and sometimes, instead of a discernible beam, a cluster of points sprouts directly from the burr.

Genetic traits can be passed through successive generations and can be very localized. For example, palmated beams might be more common in one area, while sticker points show up more often in another. They can also be more widespread, particularly in genetically isolated populations like Canada’s Anticosti Island, where bucks often lack brow tines.

INJURY-INDUCED ABNORMALITIES

INJURY-INDUCED ABNORMALITIES

Another major cause of abnormal antler growth is injury, and the type of growth varies with the type of injury.

For example, injuries to the pedicle or skull often result in abnormal growth of most or all of the antler, particularly if the injury occurs early in the growth cycle (because antlers grow from the tips). Sometimes it’s so severe there’s no growth at all. The abnormal growth, or something similar, is carried on throughout the life of the deer.

Occasionally, a deer will experience injury directly to the antler during antler growth. This can result in most or all of the antler being abnormal, and it’s often easy to distinguish. Antlers look like they started growing fine, and then went awry. You can sometimes see where a growing antler was broken, then healed and continued to grow. So long as there’s no damage to the pedicle, this type of abnormality will probably not appear in successive years.

Occasionally, there will be some injury to antler nerves. When this happens, the antler, or more precisely the nerve, has a certain amount of memory. And even if the injury heals, the abnormality can occur in successive years.

Trauma to the body can affect antler growth, too. Injury to a hind limb will result in abnormal antler growth on the opposite side, while injury to a front limb will affect antlers on the same side.

According to Kip Adams, “If the injury is severe enough to the body that it affects antler growth for that one year, even if the deer recovers, it most likely will carry that abnormality for the rest of its life.” Because abnormalities caused by injury are not genetic, they will not be passed on to offspring.

One of the strangest abnormalities is antlers that fail to shed their velvet. Undersized, non-descended or injured testes can inhibit the release of testosterone at the proper time and level. As a result, a buck can retain its velvet antlers indefinitely. Some deer, called hermaphrodites or pseudo-hermaphrodites, have reproductive organs of both sexes and appear to be antlered does.

WHAT ABOUT SPIKES?

It’s not at all uncommon for yearling bucks to have spike antlers. Conventional wisdom once said spike bucks represent inferior antler genes. We’ve since learned that yearling spikes are often late-born or undernourished fawns. Given another year or two, they often catch up to or exceed their peers in terms of antler growth. Occasionally, a buck continues to grow only spikes on one or both sides later in life, usually as a result of inferior antler genetics.

THE BIG THREE

Most hunters know the three things that most influence antler growth are age, genetics and nutrition. Fewer realize among these, nutrition is the biggest factor.

Every deer is born with a genetic blueprint — a maximum size beyond which it cannot grow, even if nutrition resources are unlimited. Few, if any, free-range deer realize their full genetic potential. Proof comes from the absurdly big racks now being produced by commercial deer breeders. Some wild deer have the genetic potential to produce 400- or 500-inch racks, but they rarely do.

In order to make the most of their potential, bucks need to reach a certain age. They’ll grow successively larger racks every year into their prime, but how big a mature buck’s rack can grow ultimately comes down to how much nutrition it can get. Nutrition includes food and water, which is why bucks tend to grow smaller racks in drier areas or in years with below-average precipitation.

WHY

We have a pretty clear idea how antlers grow, but we’re not so sure about why. Natural selection ensures that the strongest, healthiest individuals will have the greatest opportunity to mate and pass along their genes. Growing a new set of antlers every year takes a tremendous amount of energy and resources, so there must be some selective advantage.

Antlers are used as weapons, to establish dominance and fend off rivals during the rut, and as adornments to attract a mate. For reasons discussed here, antlers are a good visual indicator of an animal’s health and fitness. They could be one of several cues — others being attitude and dominance — does look for when selecting a mate. Only the healthiest males can afford to divert mineral resources to the luxury of a big rack, so a large set of antlers is an impressive pedigree for parenthood.

Facts and theories help us understand what antlers are, but they fail to explain why we are so enchanted by them.

Perhaps that’s one mystery best left unsolved.

Read Recent Articles:

• Profile of a Poacher: Whether thrill-seekers, egomaniacs, they steal from you and me.

• CSI Whitetail: High tech forensic science comes to the deer woods.

• The Magic of Acorns: It’s no secret whitetails love acorns. Here’s what you need to know.

This article was published in the August 2012 edition of Buckmasters Whitetail Magazine. Subscribe today to have Buckmasters delivered to your home.