What to do before, during and after the shot to improve recovery rates.

Shooter!”

The instant I saw the 10-pointer pop over the rise, I knew it was a deer I wanted to shoot, and it looked like I might get a chance.

I’d hemmed and hawed over several bucks earlier in the hunt, but this one was a no-brainer, and he was on a trail that should lead him right past me. The underbrush was thick, but when he entered the only opening 18 yards away, I stopped him with a mouth grunt.

Everything felt right as my crosshairs settled on his chest and I slowly applied pressure on the crossbow’s trigger. Then, much to my chagrin, nothing happened.

Things went precipitously downhill from there. I tried a little more pressure with similar results. Confusion turned to panic as I simultaneously pulled my head off the stock and my finger off the trigger to see what could possibly have gone wrong. That’s when the darned thing went off. A clean miss would have been preferable to what I saw. The unaimed arrow hit low and back, and my heart sunk as the buck slowly meandered over the next rise and out of sight.

Fortunately, I knew what to do. First I backed out as quietly as I could. Then I recruited help to take up the trail, but not until several hours later. Over a mile and a half, and nearly 20 hours later, we recovered the deer.

WHERE TO AIM

The goal of every ethical hunter is to make a quick, clean kill and recovery. To accomplish that, you need to aim for the right place. Where to aim often depends on your weapon.

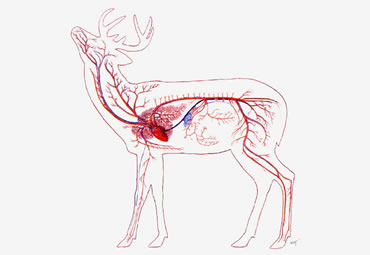

The object of an arrow hit is to cut enough veins and arteries that the animal dies from blood loss. That is most effectively accomplished with a shot to the heart/lung area. Optimum shots are broadside or quartering-away because they offer the largest target area and room for error.

A broadside bow shot should hit both lungs and/or the heart. A quartering-away shot offers a slightly smaller target area. However, puncturing the diaphragm will compromise the pressure differential between the chest and abdomen, collapsing the lungs much faster.

As shot angles increase, so do the problems. The window to vital areas becomes smaller and more protected by bone and muscle. The shooter needs to consider both entry and exit points and adjust the aiming point so the arrow passes through a vital area. For example, on a steep quartering-away shot, you need to aim farther back than you would on a broadside shot.

Bowhunters in elevated stands also must compensate for the effects of a steep downward angle. The force of gravity is greatest on an object traveling parallel to the ground. As a result, actual distance is not the same as effective distance, and archers have a tendency to overshoot. Solutions include practicing and sighting your bow while shooting from an elevated position, using a compensating rangefinder or aiming for the heart. If you miss high, you’ll still hit both lungs.

Bullets kill with shock, trauma and blood loss. In some cases, the kinetic energy alone is enough to kill, although often it is a combination of all of the above. As a result, you have a greater margin for error with a firearm. You also have more options in terms of shot placement.

In addition to the vitals, you can make a lethal shot on the shoulder, neck or spine.

When in doubt, play it safe. If you’re unsure of your shot or shooting abilities, a chest shot is a safer alternative than aiming for the shoulder or spine. If you penetrate both lungs, the deer will die, usually within 200 yards. You might have to track it and drag it a little farther, but you will find it. A near miss on a spine or shoulder could mean a long, unsuccessful tracking job.

RECOVERY

Good shot or bad, unless the animal drops within sight, you have to go looking for it. If you’ve made a good shot, that task shouldn’t be too difficult. If you make a bad shot, you have your work cut out for you. The job begins the moment you shoot. Train yourself to be able to answer several questions right away.

Where was the animal hit?

Visualize the shot, concentrating on where and how the deer was hit. Was it forward or back? Be honest. Fooling yourself into thinking you made a better shot than you did does no good. A steep angle could turn a good shot into a bad one.

How did the animal react?

You can sometimes tell where you hit based on behavioral clues. A deer shot in the heart or lungs might buck, jumping straight in the air or kicking its hind legs before bolting. A paunch-hit deer will often hunch up and walk or trot away in a humped posture. A deer shot in the shoulder or legs will exhibit an awkward gait, running erratically. Deer shot in the lungs or liver can react in a variety of ways, ranging from bolting on impact to showing complete indifference. Never assume a miss, regardless of how the animal reacts.

Where was the animal standing when hit?

This is particularly important for the bowhunter, because you’ll want to recover your arrow before proceeding any farther. It can provide vital clues to where you hit and how and when you should proceed in tracking.

Which direction did the animal go? Where did you last see and hear it? Take a compass bearing on the deer’s direction and look for landmarks. Seeing is much more important than hearing. Your eyes can play tricks on you, but your ears are much worse. Still, the more clues you collect, the better. Things can look surprisingly different from ground level.

Go through this mental checklist right away, especially if you’re in an elevated stand. You’re excited, and it will help you calm down. The answers to all these questions will also help you determine when it’s time to take up the trail.

WAIT A MINUTE

WAIT A MINUTE

The next step is often the hardest for many hunters. Unless you see the deer lying dead or hear it thrashing just out of sight, there’s no reason to go tearing off after it. In fact, it’s usually to your advantage to wait. How long you wait could be the deciding factor in how easily — or even if — you recover your deer. In most cases, it’s better to err on the conservative side. If the animal is down, it’s not going anywhere. If it’s not, you risk losing it.

Naturally, there are exceptions to every rule. If heavy rain or snow are imminent, you might want to get on the trail before it’s obliterated. Leaving a deer overnight in coyote-infested woods adds to the risk of losing it. Although it shouldn’t be necessary, you might want to proceed a little quicker on heavily hunted public land.

A general rule of thumb is that bowhunters should wait at least half an hour before taking up the trail — even on the best shot. There’s usually no harm in waiting longer. Gun hunters typically need not wait so long and usually can follow up right away. Again, much depends on where you think you hit and what the sign tells you.

CSI TIME

The first step in taking up the trail is to look for physical evidence that might help determine the type of injury. For the bowhunter, a blood-stained arrow is generally good news. The brighter red the blood, the better. Dark red blood could mean a muscle or liver hit, a signal to proceed more cautiously for bowhunters and gun hunters.

Remember the phrase: A for Away. The heart pumps life-sustaining oxygentated blood, which is bright red, away from the heart-lung region through the arteries — which tend to be deeper in the body. Darker, oxygen-depleted blood flows back to the heart and lungs through veins, which are closer to the surface. That’s why a bright red blood trail is a better indication of a lethal hit.

PAUNCH HITS

A paunch-hit deer is bad news, but not hopeless. The deer will die, and if you proceed properly, you can recover it. Check your arrow. Whether there’s blood or not, smell it. Stomach wounds sometimes bleed, but the odor of stomach contents is unmistakable. If conditions allow, wait a minimum of four to six hours before taking up the track; 12 would be even better. I recovered two paunched bucks that were still alive 12 hours after they were shot. Both had traveled less than 100 yards.

Proceeding too quickly on a blood trail is one of the most common mistakes deer hunters make. Unless you saw the deer drop, you should have a plan and follow it to the letter. Again, there are very few circumstances that call for haste, even impending darkness.

Being patient forces you to slow down so you don’t overlook details. Besides blood, you should be looking for other evidence of a hit, such as hair or bone. Also look for dig marks where the deer jumped. You might have to dry track for some distance before picking up blood.

I’ve dry-tracked deer for several hundred yards by getting down on my hands and knees and literally placing my fingers in the indentations made by their hooves.

DON’T GIVE UP WITHOUT A FIGHT

DON’T GIVE UP WITHOUT A FIGHT

If you run out of sign, you still have options. One of the most effective I’ve found is simply to follow deer trails away from the last sign. Another is to walk circles around the point of last blood or sign. If you have help, do a grid search. In this case, the more bodies the better. Line up close enough so you can see the feet of the person next to you. Have one person be the leader, and work the line in a compass direction — go north to south or east to west.

WHEN TO GIVE UP

If you hunt long enough, you’re going to wound a deer and not recover it. There are countless reasons why, but you can take solace in the fact that deer have an amazing vitality and often recover from what you might consider a fatal wound.

I once shot a buck that had been wounded earlier the same season. I didn’t detect anything wrong with it until butchering it, when I discovered its femur had been shattered by a shotgun slug. The wound was already healing into a mass of bone. I also shot a buck that was missing the lower half of a hind leg. The wound had healed over completely and the deer appeared to be doing fine, except for a slight limp.

Editor’s note: Parts of this article are excerpted from Bob Humphrey’s new book, “Pro Tactics: Whitetail Hunting,” available from Globe Pequot Press.

Read Recent Articles:

• The Ultimate Practice: The best way to get really good at taking whitetails is to ... take lots of whitetails.

• What’s New in Whitetail Research? Studies in Alabama and Wisconsin shed light on breeding and mortality.

• Faith Buck: It took four years to bag this whitetail, but it was worth every minute.

This article was published in the September 2011 edition of Buckmasters Whitetail Magazine. Subscribe today to have Buckmasters delivered to your home.