By C.J. Winand

Can hunters learn anything useful from deer droppings?

We’ve all read that you can tell the sex of the deer by the size and shape of droppings, but is that really true? Do biologists really know? And, more important, can hunters learn anything from all the deer droppings they observe? The science of deer pelletology is intriguing, and despite the sometimes humorous tone of this article, you really can learn a lot about the deer in your area by studying their poop.

We spend a lot of time analyzing deer sign like rubs and scrapes, but there are a lot more deer pellets in the woods, and they hold clues about deer behavior. If you understand how to read all forms of deer sign, including droppings, you’ll be a better hunter.

My good friend Bill Belton and I were discussing the “science” of deer droppings and what it can mean to hunters. You might ask, “What can I learn from a bunch of deer droppings?” or “Can we actually get closer to deer by learning something about deer pellets?” or “Do all deer defecate in the same area?” or “Are buck droppings larger than doe droppings?” and so on. Surprisingly, all of these questions have been answered by the scientific community.

Whenever you come across a pile of droppings, the shape can give you many clues as to what the deer has been eating. Generally, round individual droppings indicate the deer has been foraging on leaves, browse and twigs; pellets lumped together (all-in-one) suggest the deer has been focusing on grasses, weeds and forbs.

Many hunters claim that they can determine the sex of a deer from the size of individual droppings.

Research analyzing pellets from penned deer suggests the average hunter can’t identify does from bucks by the size of their droppings. One Georgia study found that there were slight differences in the length of the droppings between bucks and does, but those deer were all eating the same pellet rations. Thus, comparing the results of this study to free-ranging deer is not advisable. In fact, some of the trophy deer droppings I’ve observed have come from penned does. An exception occurs when you have bucks 4 1/2 years old or older in your area. However, considering that most of the country supports high percentages of younger bucks, betting that the large droppings you’ve found will lead you to a record-book buck wouldn’t be wise.

Research analyzing pellets from penned deer suggests the average hunter can’t identify does from bucks by the size of their droppings. One Georgia study found that there were slight differences in the length of the droppings between bucks and does, but those deer were all eating the same pellet rations. Thus, comparing the results of this study to free-ranging deer is not advisable. In fact, some of the trophy deer droppings I’ve observed have come from penned does. An exception occurs when you have bucks 4 1/2 years old or older in your area. However, considering that most of the country supports high percentages of younger bucks, betting that the large droppings you’ve found will lead you to a record-book buck wouldn’t be wise.

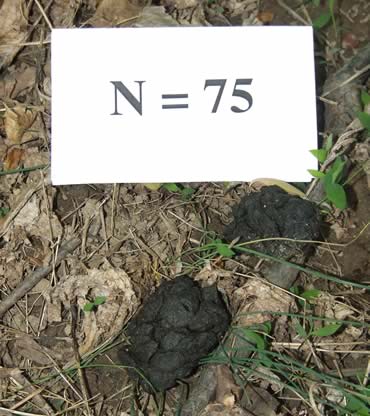

Back in 1940, researcher Logan Bennett came up with an idea that is still used in deer management today. He found that deer defecate 12.6 or, say, 13 times per day. That’s right, count ’em, 13 times (I guess they cut it off at “.6” at the end of each day?) It’s no wonder that some hunters say they can actually smell deer. And if you’re wondering if those large piles are from bucks, biologists have found that some adult bucks do, in fact, produce more pellets per group. Studies also indicate that 75 is the average number of pellets. So, the next time you wander onto a world-class poop pile, you just might be a short distance behind (literally) a deer of a lifetime.

Another important question deer hunters always ask biologists is, “How many deer are there in this area?” The answer, or at least a very close approximation, can be found in the number of droppings in the area. Pellet counts are used by many state wildlife departments as a component to estimate deer populations.

Bennett and other biologists determined the defecation rate for deer by simply walking various transects along a one-square-mile area and counting every “pile.” Hunters can easily do the same. Those in northern states would be advised to conduct this population index 24 hours after a snowfall. For example: After one day, if you count 195 droppings along your transects, simply divide by 13. The density of deer within your hunting area is 15 deer per square mile. As with any population index, the more times you sample your area, the more accurate your results.

Other researchers have found that deer average 26.2 (there’s that fraction again) piles of dung per day in the spring compared to the average of 13 in the fall. This is probably due to the increasing amounts of fiber added to the bulk feces between spring and fall. Evidently, as the diet changes from succulent leaves and forbs in spring to mature vegetation in summer to more course items in fall after leaf-drop, the number of pellet groups decreases. Other data indicates that defecation rates among adults and juveniles also differ with diet. Researcher Dr. Ron Ryel found that bucks might have a higher defecation rate than does in winter.

What else can research tell us about a bunch of droppings? Did you know there are three ways a deer can defecate in the woods? They can drop pellets in a random, uniform or clumped distribution. They deposit droppings in a clumped distribution in and around bedding and feeding areas. This is a very important field clue because, just like many people, shortly after a good meal, they’re off to the “reading room.” It’s also one of the first things they do upon getting up in the evening.

What else can research tell us about a bunch of droppings? Did you know there are three ways a deer can defecate in the woods? They can drop pellets in a random, uniform or clumped distribution. They deposit droppings in a clumped distribution in and around bedding and feeding areas. This is a very important field clue because, just like many people, shortly after a good meal, they’re off to the “reading room.” It’s also one of the first things they do upon getting up in the evening.

Whenever you find a lot of deer pellets in a relatively small area, you’ve ventured close to one of two areas: feeding or bedding. Since bedding areas are sometimes difficult to locate, and since you don’t want to push deer from their beds while hunting, feces can be a great way to pinpoint a buck’s bedroom.

Another clue we can identify from pellets is the specific type of forage deer are keying on. With a little practice, you can identify the different plant and mast species in a deer’s droppings. In fact, I know some wildlife graduate students who say picking through the various specimens is fun! While you’re at it, I suggest stepping in deer pellets while hunting. Better yet, rub them all over your hunting clothes and treestand. Before you think I’m crazy, hear me out.

[Editor’s Note on this matter: We report, you decide!]

Did you ever wonder why a dog will roll all over a dead rabbit or opossum? His instincts tell him that if he can cover his predator scent with that of a prey species, he will become a more efficient predator. Hunters who step in cow manure (on purpose) or roll or rub deer pellets onto their clothing and treestand can effectively cover some of their human scent. Since droppings are located almost everywhere and they’re free (yes, my buddies say I’m cheap), you couldn’t ask for a better cover scent.

To prove this point, another biologist and I took droppings from one deer pen and placed them on the ground of a separate pen containing different deer. The results were very interesting. The typical response included a matriarch doe and its fawns approaching to investigate the strange droppings, smelling them and simply continuing on with their feeding.

Our next test was on wild free-ranging deer. Just like the penned deer, the wild deer checked out the unfamiliar odor but did not exhibit any alarm behavior. Before conducting these tests, we hypothesized that, since penned and wild deer were able to identify other individual deer within the herd by smell, the scent of droppings from a foreign deer might cause some degree of alarm among the local deer. This definitely was not the case. We also wondered what type of behavioral responses we would observe if we used urine and feces from other species.

Before we could actually test our hypothesis, I discovered an actual “feces thesis” done by researcher Howard Steinberg. Steinberg tested the response from deer encountering feces from other herbivores (vegetation feeders), omnivores (both vegetation and meat eaters) and carnivores (meat eaters). He found that deer had the greatest aversion toward the feces of carnivores from animals like timber wolves, dogs, bobcats and cougars. Interestingly, no matter how many times the carnivore samples were presented, the deer always exhibited alarm behavior. What about the other samples? Deer showed some aversion to the omnivores, but not as much as the carnivores and hardly any avoidance of feces from herbivores.

The most important finding in these studies has been that deer showed the greatest interest in the pellets from deer of separate herds. Whenever you hunt an area, it’s wise to collect those special little woodland nuggets in a plastic bag and use them near your stand in a different hunting area. Since deer are generally curious animals, this technique could be the final trick you need to bag your deer. Finally, I would be neglectful in my duties if I didn’t mention that those woodland nuggets keep quite well in your freezer.

So do you still think I’m “full of it?” That just might be, but the science of deer pelletology really can help you key in on several aspects of deer movement and patterns.

Read Recent Articles: • Making It Count: Missouri teenager makes the most of his last season as a youth hunter.

• If Mama Ain’t Happy: Bucks get all our attention, but the life and habits of does are just as interesting.

• New Year’s Eve Bonanza: Talk about waiting until the last minute to make a deer season!

This article was published in the September 2008 edition of Buckmasters Whitetail Magazine. Join today to have Buckmasters delivered to your home.