How this little understood arrow factor can make or break your setup.

Just the other day, I shot a dozen arrows of an unfamiliar brand to check their performance at 50 yards. That’s a good distance for practicing, because it makes traditional whitetail distances seem like chip shots. When you practice regularly at this distance, you learn a lot about how forgiving your bow setup really is. If it’s singing a sweet tune, you can get away with minor flaws in form; each arrow will land pretty much in the middle of the pack. I’m not saying the group will be as tight as Britney Spears’ blue jeans, but your arrows should stack a lot tighter than the pants of an MTV rapper.

Historically, archers in the know have relied on arrow shafts with the tightest tolerances in straightness and weight to optimize bow forgiveness. Naturally, a true arrow should outperform one that’s not true. But the truth is, a third characteristic of an arrow, its spine, might be more significant than those other variables.

Spine Defined, Spine Refined

Spine Defined, Spine Refined

The “spine” of an arrow is defined by how it reacts when pressure is applied. Like the IBO speed rating, arrow spine is a calibration based on a set of exacting assumptions: The figure is derived from suspending a 1.94-pound weight over a span of 28 inches of arrow shaft. The reading, in thousandths of an inch, becomes the spine of that particular shaft. Hence, the larger the number, the greater the deflection bend and the weaker the spine. A smaller number reflects a stiffer spine since it deflects less.

This is a static (stationary) spine measurement and forms the basis of arrow selection charts that take into account bow weight. Bows set at heavier weights require shafts with less deflection (more spine), and bows set at lighter weights require shafts with more deflection (less spine). The reason is that lighter bow weights matched to lighter arrow weights cause a decrease in dynamic efficiency, which allows them to accommodate softer arrows.

Deflection is a big deal in archery. The phrase “straight as an arrow” is a gross misconception. When shot from a bow, an arrow bends and oscillates. Eventually, the recovery properties of the shaft and the steering effect of the fletching straighten out the arrow. So the issue isn’t whether an arrow bends, but does it bend too much or too little? Although bowhunters tend to choose stiffer arrows over softer ones, an overspined (too stiff) arrow flies just as poorly as an underspined (too limber) arrow. You need to get it right. When you do, your arrows will neither porpoise nor fishtail, and your fletching will zip through the rest unhindered. That is my definition of a forgiving setup.

Matching arrows to bows is no different from matching tippets to fly line, tires to cars or neckties to shirts. Some combinations are simply superior to others.

A Lesson from Golf

A Lesson from Golf

Golf and bowhunting share striking similarities: No two shots are exactly alike, and carbon-shaft technology has changed everything. Indeed, carbon (aka graphite) is king in golf because it improves driving distance by a huge margin. Likewise, carbon rules in bowhunting because carbon shafts ramp up arrow velocity while increasing durability and penetration.

But carbon is not the easiest material to work with; shaft-to-shaft inconsistencies are inevitable. Carbon material requires a substantial curing process and is sensitive to minute variations in temperature and humidity. Also, the layering process for creating shafts must be precise to avoid gaps and overlaps. Typically, better shafts use laborious computer- and laser-controlled processes with higher grades of carbon. Nevertheless, structural irregularities occur in every golf shaft and every arrow shaft. The key is minimizing inconsistencies while quantifying them to avoid erratic results.

Although golf shafts are manufactured and rated by stiffness to tight specifications, touring professionals can’t avoid the driving range to decide which clubs they’ll use for tournament play. Some players include an extra step, the patented “puring” process. It’s an alignment procedure that determines the most stable position, or orientation, of each shaft. Club-makers use a $500 machine, the Digi-Flex, to measure oscillations in determining the best orientation. To assure square contact at impact, clubs are marked at the ideal oscillation point before grips are applied. I’ve used one of these machines for about a decade, and it’s improved my play.

Start with the Right Shaft

Start with the Right Shaft

Because bows shoot arrows at essentially the same speed every time, bowhunters don’t need to test dozens of shafts to get the right spine for their bows. The starting point is selecting the spine rating that matches your setup. Like golf manufacturers, arrow makers segregate shafts by stiffness. Spine selection charts incorporate bow weight and other factors that affect dynamic (moving) spine. Today, most arrow companies only offer two or three spines to accommodate all bowhunters. As a result, it’s fairly common to fall toward the edge, or even between, shaft ratings instead of landing in the middle of the bell curve.

I conducted a simple experiment with a dozen “economy” arrows. Six were tipped with 100-grain points; the remaining six were tipped with 125-grain points. All were shot with a 60-pound Mathews DXT out of a Hooter Shooter equipped with a Scott Archery Little Goose mechanical release. As expected, two impact groups resulted, with the 100-grain-tipped arrows landing higher than the 125-grain-tipped arrows. However, more groups emerged within these groups. In short, by adding and subtracting 25 grains of weight, I was able to make the arrows perform as if they were softer and stiffer, respectively. Adding weight makes an arrow bend more, and subtracting weight causes the arrow to resist bending. My bow liked the stiffer arrows (those tipped with 100-grain points) a lot more than the softer ones (with 125-grain points). In fact, the former grouping was at least 40 percent tighter than the latter.

This exercise explains some of the mysteries bowhunters commonly encounter when experimenting with different shafts and different broadheads. That’s why lower-grade arrows (tolerance rating of plus or minus .006 inches or more) can be made to group tighter than premium shafts (tolerance rating of plus or minus .002 inches or less) and why a heavier (or lighter) broadhead can appear to be more forgiving.

Spine Orientation

Spine Orientation

Most archers look up spine selection charts and cut arrows to match their draw length. I recommend an extra step to make your bow as forgiving as possible. The same process golfers use — evaluating and fine-tuning shaft orientation — can tighten arrow groups significantly.

If every shaft wall possessed a uniform thickness (360 degrees around its column), we wouldn’t need this procedure; arrows would release from the bowstring at the same exact stiffness, or oscillation, and would share the same exact dynamic stiffness. But, as we have seen, this is a pipe dream. When the smoke finally clears, we need a method to orient arrow shafts just like golfers orient theirs.

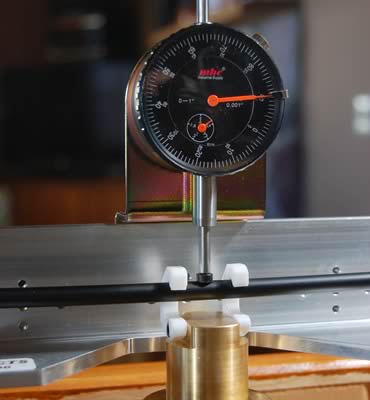

This can be accomplished by a little-known tool, the QV Spine Tester from Ram Products. This device has a gauge that converts deflection to thousandths of an inch. Once a shaft’s stiffest point is determined, nocks can be oriented in line with it, and fletching can then be applied (cock vane up or down).

Manufacturer Tech Talk

I interviewed representatives from Easton Technical Products, Carbon Express and Gold Tip to find out how they feel about arrow spine consistency.

Easton’s Gary Cornum and Carbon Express’ Lennie Rezmer agree that inconsistent spine is a contributing factor to arrow performance. Gold Tip’s Tim Gillingham said other factors, particularly straightness at the tip and at the nock, might be equally, if not more, important.

A word of precaution when attempting to compare spines from different arrow manufacturers: With the exception of Easton, never assume model numbers correspond to spine numbers. Examples: Gold Tip’s 55/75 is a 400-spine shaft that measured about 415 (thousandths) on my QV scale; Beman’s MFX 400s generally measured closer to 410; Carbon Impact’s 6000 Fat Shaft averaged 410; and Carbon Express’ 250 Aramid KVs hovered around the 402 mark. These are average spines for a group of a dozen, with the highest and lowest eliminated to avoid skewing numbers.

With all this in mind, following are three spine rules for making a smart purchase:

• Never buy arrows a dozen at a time. If you get them in lots of 24 to 48, you can cull the extra-soft and extra-stiff shafts and reserve them for practicing.

• Buddy-up when purchasing arrows to take advantage of rule number one. Since the vast majority of bowhunters require a 400-spine shaft (bow weights ranging from 55 to 65 pounds), you can divvy up the arrows based on where everybody lands on that brand’s spine selection chart.

• Know exactly what you’re buying. Always verify the actual spine of a prospective make and model prior to making a purchase; make this a condition to the seller.

• If you can’t afford a QV Spine Tester, either share the cost with your network of buddies or use the multi-purpose Arrow Inspector from Pine Ridge Archery (www.pineridgearchery.com, (877) 746-7434). It spins an arrow so smoothly that many shafts will likely come to rest at a heavy-spine-down orientation.

No doubt some archers lack the proficiency to tell the difference between a smart-missile arrow and a scud-missile arrow. But if you’re truly searching for the ultimate hunting shaft, achieving spine consistency for every arrow in your quiver is an excellent place to start.

Read Recent Articles: • Big Woods Bucks: Whitetails in large timber tracts are harder to pattern, but it’s not impossible.

• Antler Intrigue: Of the recognized big buck factors, which is really most important?

• The 5 Ws of Decoying Deer: Who, What, When, Where, How and Why to use deer decoys

This article was published in the August 2008 edition of Buckmasters Whitetail Magazine. Join today to have Buckmasters delivered to your home.