Deer hunters in Alabama currently are likely experiencing the gamut of rutting activity across the state. Because of the state’s diverse topography and wildlife management heritage, some hunters may see deer in the heat of rut, while others are watching young bucks start to chase does as the rut kicks off. For others, the rut is so 2015.

A study conducted by Mississippi State University provided some insight into why the South has such a wide range of rutting periods.

The study concluded the genetics that determine when rutting activity begins is controlled by the lineage from the does. The bucks’ genetics have very little to do with the timing of the rut except in extreme cases where a population may have been virtually wiped out.

The conclusions from the MSU study are logical to Chris Cook, Deer Project Study Leader with the Alabama Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries Division.

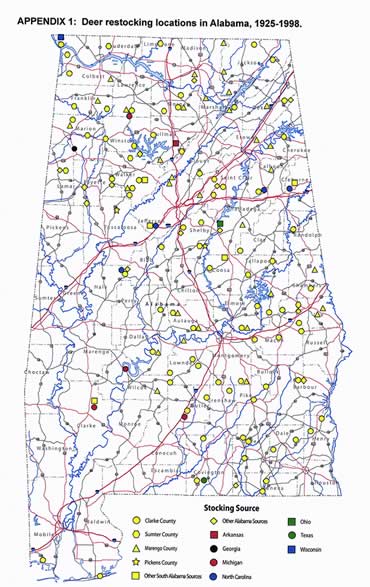

“With the collections we’ve done since 1995, looking at conception dates across the state, there’s definitely a connection to the stocking source, especially in those areas where we have documented restocking from sources outside Alabama,” Cook said.

“Most hunters in Alabama are aware that in the upper Black Warrior WMA (Wildlife Management Area), there was a pretty large release of deer from a source in Iron Mountain, Mich., in 1927. Over the years, we’ve released deer from other places in Alabama.”

Cook said WFF Biologist Francis Ludeh performed conception date studies back in the 1950s and ’60s when many of the relocations and restockings were taking place.

Cook said WFF Biologist Francis Ludeh performed conception date studies back in the 1950s and ’60s when many of the relocations and restockings were taking place.

Ludeh found even back then the conception dates in the Black Warrior area and the Bankhead National Forest were from mid to late November because those deer came from Michigan stock.

“Even with all that influx of Alabama deer back into that population, those deer are still breeding in mid to late November,” Cook said.

“The Mississippi State study makes sense. Deer that are released from whatever source into an area with no deer or very few deer, it stands to reason the genetic makeup of that population is going to keep that component of those original does unless something drastic happens and the area is restocked with deer from other areas.

“That’s what happened at Black Warrior. When those deer were released there were hardly any deer in there, so it was basically only Michigan deer. Any deer introduced since then were not enough to overwhelm that original stocked population.”

Cook said the Oakmulgee WMA and Choccolocco WMA in Talladega National Forest were stocked with deer from Pisgah, N.C., back in the 1940s, and those areas have maintained a much earlier conception date than the bulk of the rest of the state.

“The population in Choccolocco has maintained a rut similar to Black Warrior from mid to late November,” Cook said. “The deer in Oakmulgee tend to breed the first 10 days of December.

“On the flip side, there are parts of north Alabama that were stocked with deer from Clarke County (southwest Alabama) that have late ruts in late January and early February. There are some areas around Freedom Hills WMA that were stocked with south Alabama deer that have a late rut. You can go back to the restocking records and tell if the area was stocked with a certain number of deer from Clarke County.

“On the flip side, there are parts of north Alabama that were stocked with deer from Clarke County (southwest Alabama) that have late ruts in late January and early February. There are some areas around Freedom Hills WMA that were stocked with south Alabama deer that have a late rut. You can go back to the restocking records and tell if the area was stocked with a certain number of deer from Clarke County.

“Of course, there are areas in west Alabama where there are no records of restocking, and those conception dates are similar to the majority of Alabama north of Highway 80. There you have conception dates from Christmas to mid-January.”

Cook said there was very little restocking of deer in Alabama south of Highway 80, which means the rutting activity is relatively consistent across the southern third of the state.

Intensive management of a particular deer population can change the breeding activity, but not by much, according to Cook.

“If an area is managed for an older buck population where you have a good percentage of 3-year-old-plus bucks in the population and a tight buck-to-doe ratio, typically you can have a rut that gets started a little earlier compared to a place that is not intensely managed,” he said.

“That conception date may move up a week but probably not more than 10 days. You’re not going to get a native Alabama deer population to breed in November. It’s going to be Christmas to early February, depending on what part of the state you’re in.”

Cook said WFF personnel collected data last year from deer herds on opposite sides of the Warrior River to compare population dynamics.

“One property is managed intensively for mature bucks for 20 years,” he said. “The property on the other side of the river was not managed as intensively, and there was an eight- to 10-day difference in the conception dates. That’s what happened in one year. We’ll see if that holds true on down the road.”

Cook said Alabama’s deer are like almost any deer population when it comes to rutting activity from pre-rut to post-rut.

“We’re just like any other part of the country,” he said. “Our deer will have a pre-rut before the actual breeding takes place. Then we have a post-rut where the deer basically seem to go underground.

“Typically, in the pre-rut, people will see a lot of bucks because they’re chasing the does around. In the actual rut, you won’t see as many bucks because the does are standing and being bred. Then you’ll get another flurry of activity when most of the does have been bred but there are a few that aren’t. All the bucks are looking for those does that didn’t get bred.”

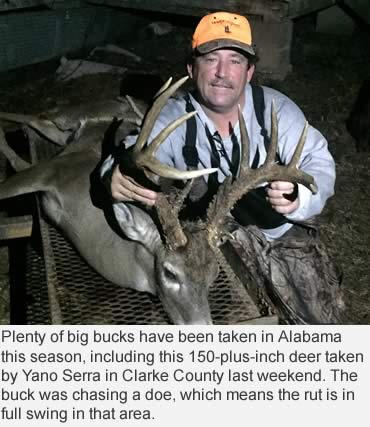

For the second year in a row, social media has been blowing up with photos of huge bucks that have been taken in Alabama. Cook thinks there could be several factors contributing to the number of trophy bucks taken.

“I think one reason is a change in the mindset of hunters,” he said. “People are passing 1- and 2-year-old bucks, which means more make it to the 5-year-old age group. Of course, you can’t discount the effect the three-buck limit has had. It sure appears that has had an effect, but I think the change in mindset of letting a young buck walk has probably had as much to do with it as anything.”

— Photos courtesy Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources