Photo: This laughing barn owl just ate a vole.

They are rodent-killing machines whose presence is so welcome that farmers and landowners build nesting boxes to encourage them to stay.

You will find them on every continent, except Antarctica, which makes them the most widespread land bird in the world.

Have you guessed this bird’s identity? It’s the common barn owl.

Despite being identified as common, barn owls have collected a lot of different names, some which might seem to contradict another: monkey-face owl, ghost owl, church owl, death owl, hissing owl, night owl, hobby owl, golden owl, silver owl, white owl, rat owl, scritch owl, screech owl, straw owl, barnyard owl and delicate owl.

You won’t hear this raptor hooting; that sound belongs to Great Horned owls who claim their territory with their voice. Instead, barn owls shriek and use variations of their shriek, or screech, to communicate or warn away predators, which sometimes are larger raptors.

In the owl family, barn owls are medium-sized birds, 15 to 20 inches in height, with very long feathered legs.

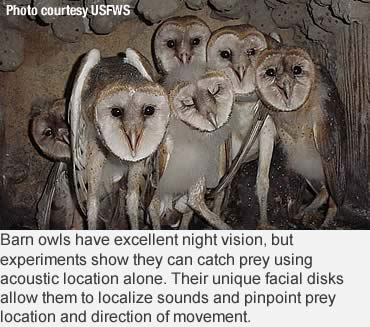

They have 3- to 4 1/2-foot wingspans, and their feathers are gold, white and cinnamon colors with small dark spots and dark eyes. A heart-shaped ruff completely encircles their face, and they do not have ear tufts, although one ear is slightly higher than the other which allows them to pinpoint sound. Their feathers are very soft and soundless in flight, which enables them to hunt silently.

They have 3- to 4 1/2-foot wingspans, and their feathers are gold, white and cinnamon colors with small dark spots and dark eyes. A heart-shaped ruff completely encircles their face, and they do not have ear tufts, although one ear is slightly higher than the other which allows them to pinpoint sound. Their feathers are very soft and soundless in flight, which enables them to hunt silently.

This nocturnal bird of prey hunts mostly at night, and with their super-sharp vision and hearing, they can locate even the smallest mouse or vole, even under snow cover.

What makes them so welcome are their rodent dining choices.

According to the Barn Owl Trust, a United Kingdom charity that works to conserve the owl, a single wild barn owl typically eats four small mammals (voles, shrews, mice and rats) every night for a grand total of 1,400 pests annually. They also consume lizards, birds, insects, bats and rabbits.

Sara Kross, assistant professor of environmental studies at Sacramento State University, has called barn owls rodent-killing machines. “They are natural predators of gophers and voles which can be really horrible pests for agriculture.”

But it’s a tricky situation, she explained, because one pest-control method can affect another. As good as owls can be at controlling rodents on farms, growers may still need rodenticides to control population explosions. And, because rodenticides don’t kill immediately, barn owls can eat voles, mice and rats exposed, which can limit the owls’ ability to hunt and control pests.

You won’t often see a barn owl during day, and they choose secluded places to nest, like tree cavities, abandoned buildings, grain bins, silos, barns and church steeples. During a study in Iowa that examined a drop in barn owl numbers, biologists even found a nesting pair in a deer stand.

You won’t often see a barn owl during day, and they choose secluded places to nest, like tree cavities, abandoned buildings, grain bins, silos, barns and church steeples. During a study in Iowa that examined a drop in barn owl numbers, biologists even found a nesting pair in a deer stand.

Except in their northernmost range, barn owls, who mate for life, typically raise two broods each year, in spring and late summer. Young owls, fed by both parents, mature between 10 and 12 weeks. Unfortunately, barn owls do not live longer than a year or two.

Land managers and farmers documented nests and sightings during Iowa’s recent five-year study with hopes to increase the owls’ presence along grassland field edges, fencerows and wetland edges where the habitat loss also led to lower numbers of barn owls.

You can learn more; many state conservation departments feature additional information about barn owls and offer free plans to build predator-proof nesting boxes.

– Resources: USDA, USFWS, Iowa Department of Natural Resources, Missouri Department of Conservation, Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, The Barn Owl Trust.