Photo: If this fawn could speak, it would say “I’m fine. Mom is watching. Leave us alone.” – Photo courtesy Deb Watson.

It happens every spring. Instead of taking a photo and moving on, soft-hearted humans are kidnapping wildlife babies.

Helpless deer fawns born in April, May and June are hidden by their mothers. Tiny, newly feathered birds fall from their nests. Baby rabbits outgrow their hiding places. Nearby, the animal parents watch, helplessly, as well-intentioned humans kidnap their babies.

Why this happens is not a mystery.

Nothing is cuter and cuddlier than a wildlife baby. In reality, most young wildlife reported as found or discovered are not orphaned. Although people who attempt to rescue wildlife babies believe they are going good, they are, in fact, dooming the very creatures they intend to help.

The babies haven’t been orphaned; they’ve been left alone on purpose. The solitary spotted fawn in the woods or along a roadway hasn’t been deserted. It has been hidden and is still in the care of a doe. The same is true for the birds and bunnies.

It's part of nature's plan for a doe to leave her fawn or fawns alone for their first few weeks of life. After brief periods of feeding and grooming her fawn, a doe spends much of her day feeding and resting. Her fawn ordinarily stays bedded down as if sleeping, but will occasionally move short distances to new bedding sites.

It's part of nature's plan for a doe to leave her fawn or fawns alone for their first few weeks of life. After brief periods of feeding and grooming her fawn, a doe spends much of her day feeding and resting. Her fawn ordinarily stays bedded down as if sleeping, but will occasionally move short distances to new bedding sites.

Rescuing a baby from its mother not only shows bad judgment, it is illegal in many states. However, whether they are adults or young, all species of wildlife have highly specific needs for survival.

"Taking wildlife out of their environment and into your home often takes away that animal’s ability to then survive in the wild, where they belong,” explains Kaitlin Goode, program manager of the Georgia WRD Urban Wildlife Program.

“In most instances, there is an adult animal a short distance away—even though you may not be able to see it. Adult animals, such as deer, spend most of the day away from their young to reduce the risk of a predator finding the young animal.”

The best thing anyone can do when they see a young animal, or in fact any wildlife, is to leave it exactly as they found it. Situations become much more complex, and sometimes pose a danger to wildlife or people, when an animal is moved or taken into a home, Goode explains.

During spring, DNR field offices across the country are inundated with phone calls and, too often they find scores of not-really-orphaned wildlife kidnapped from their mothers.

Iowa’s Department of Natural Resources reports during a typical spring season, the species range from baby robins and squirrels to white-tailed fawns. It is not uncommon for staff to discover entire litters of baby raccoons, foxes or even skunks mysteriously left on their doorsteps.

Many wildlife babies die soon after capture from the stress of being handled, talked to, and placed into the unfamiliar surroundings of a cardboard box. Should the animal have the misfortune of surviving this trauma, they often succumb more slowly to starvation from improper nourishment, pneumonia or other human-caused sicknesses.

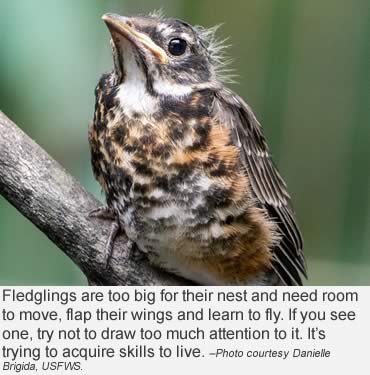

For many songbirds, the transition to independence comes quickly and may take as little as four or five days. For other species such as Canada geese, kestrels or great horned owls, the young and parents may stay in contact for weeks or months.

For many songbirds, the transition to independence comes quickly and may take as little as four or five days. For other species such as Canada geese, kestrels or great horned owls, the young and parents may stay in contact for weeks or months.

There’s an additional troubling situation.

Each spring and summer, the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources gets many calls from people who have discovered young, lost deer, and then have taken them home to raise them. It’s a situation that grows into a problem without a happy ending.

If the fawn doesn’t die from the stress of being saved, fawns taken into captivity grow into semi-tame adult deer that can become dangerous. Adult buck deer, no matter how gently they were raised, are especially dangerous during the breeding season. Even does raised by humans are unpredictable.

Occasionally, deer thought to be tame seriously injure people and, in cases where the deer are a threat to humans, the deer sometimes have to be killed.

Rescuing wildlife babies—also known as kidnapping them—is a dreadful problem with a simple solution: Leave the wildlife babies alone. Take a photo and move on.

– Resources: Iowa Department of Natural Resources, South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Wildlife Resources Division.