Photo: A juvenile Eastern indigo snake was recently discovered in Conecuh National Forest, which is the first evidence of reproduction in Alabama in more than 60 years. - Photo courtesy Francesca Erickson, David Rainer.

Traci Wood admitted holding the snake almost made her come unglued. No, she wasn’t afraid of the snake she was holding.

It was the magnitude of the moment.

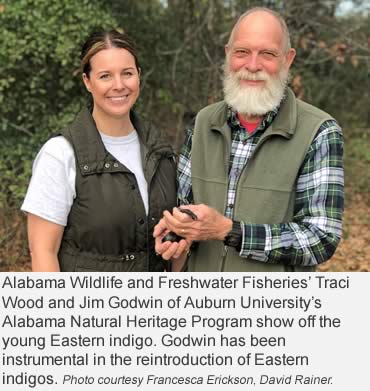

Wood, the habitat and species conservation coordinator with the Alabama Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries (WFF) Division, had in her hands the first wild Eastern indigo snake documented in Alabama in more than 60 years. Eastern indigos were extirpated from the state and haven’t been seen since the 1950s.

“I’m not embarrassed to say that I was shaking when I held that animal,” Wood said. “This is a monumental benchmark in conservation for Alabama and the southeast region for this species.

“It’s a big deal, extremely big. It’s big for recovery efforts of a federally listed threatened species. It’s the first documentation of a wild snake in more than 60 years in Alabama. It’s proof that what we are doing through reintroduction is working, and that captive snakes are acting like wild snakes after they are released.”

Technicians from the Auburn School of Forestry and Wildlife Sciences and the Auburn Museum of Natural History were out looking for documentation of indigo snakes as part of the long-term program to re-establish viable populations of Eastern indigos in their native habitat, mainly in longleaf pine forests in central and south Alabama.

“We try to document how long they are living, how far they are moving and how they’re doing health wise,” Wood said. “The technicians were out and came across the snake as part of the monitoring effort. There’s always the hope that we will find documentation of reproduction, and it finally happened.”

Wood said the technicians knew immediately what they had discovered when the snake was picked up.

Wood said the technicians knew immediately what they had discovered when the snake was picked up.

“They knew because it was a hatchling-size snake,” she said. “It measured 2 feet in length, which is much smaller than the snakes we release from OCIC (Orianne Center for Indigo Conservation). It had no PIT (passive integrated transponder) tag or any indication we use in monitoring to indicate it was a released snake. Those released snakes are 5 feet in length or longer. They estimated the juvenile indigo at about 7 months old. It probably hatched in July or August.”

The Eastern indigo project, which started in 2006, released 17 adult captive-raised indigos into the Conecuh National Forest in 2010. To date, the project team has released 170 snakes, with a goal of releasing 300 snakes to improve the chances of establishing a viable population.

During the early days of the indigo project, the released snakes were propagated from indigos that had been captured in the wild in Georgia.

Partners in this project include Auburn Museum of Natural History, Auburn School of Forestry and Wildlife Sciences, U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Zoo Tampa, Zoo Atlanta, the Georgia Department of Natural Resources and the U.S. Army’s Fort Stewart, as well as the OCIC at the Central Florida Zoo, where the captive indigo breeding and health care are handled.

“We’re kind of at the halfway mark in the reintroduction,” Wood said. “It’s very exciting to see verification of reproduction at this stage of the project.

“It’s a huge testimony to the State Wildlife Grants program and working toward the recovery of a federally listed species. It is considered an experimental population. We were conducting research and making decisions that had never been done before with this species. It was a lot of groundbreaking work.

“Florida now has a reintroduction program, and a lot of their work is based on what we’ve done at Conecuh and lessons learned at Conecuh. Besides aquatic species, there isn’t another example of species recovery of a federally listed species through reintroductions.”

Wood said 2-year-old snakes have a better chance of survival in the wild because they are less susceptible to predators.

__________________________________________________________________

Photo:

Considered an apex predator, the Eastern indigo snake is not venomous. Although it is harmless, it plays an important role in the longleaf pine ecosystem. Its most notable feature is the lustrous, glossy, iridescent blue-black coloration of its head and body. Reaching a length of 8 to 8.5 feet, the Eastern indigo is longest snake native to the U.S. It feeds mainly upon other snakes, all venomous snake species to the Southeastern U.S., as well as turtles, mammals, frogs, birds and lizards. Indigos are known to range far and wide during the warmer months and then seek refuge in the gopher tortoise burrows during the winter. -

Photo courtesy Kevin Enge, Florida Fish and Wildlife

__________________________________________________________________

“We also learned the target for the number of individuals to be released,” she said. “That is 30 individuals per year. We’ve learned that we had to establish a monitoring program that didn’t exist before. We learned it takes intense monitoring on the ground.”

One of the tools the monitoring team borrowed from the hunting community is the game camera. The game cameras have been stationed to monitor activity at gopher tortoise burrows, which are utilized by a number of animals, including indigos.

“We had to learn that a snake is not going to trigger motion sensitivity on the game cameras,” Wood said. “We set the cameras to capture a photo at intervals of 30 to 60 seconds to make sure we capture all the activity. That’s something we’ve recently started and, so far, it’s proven to be very helpful. We’ve captured pictures of several indigos at burrows.

“The cameras are showing location, where they’re hanging out, how they’re using burrows and the fact adult snakes are surviving. We estimate that 60 to 80 percent of the snakes that we reintroduce will survive. That’s not bad at all after they’ve been in captivity for two years.”

Wood said it is not possible right now to estimate the total number of Eastern indigo snakes in the Conecuh habitat. “These recaptures and verification of reproduction is data that will be useful in the future. Someday we may be able to predict how many individuals may be in the wild.”

She is still having a little trouble grasping what happened recently. “Physically holding a wild species that hasn’t been documented in Alabama in more than 60 years gives us high hopes for what we may see when we reach our goal of 300 snakes released,” she said.