Photo: The bobcat is the most common wildcat in North America, but it’s easily misidentified as its cousin, the lynx. – Photo courtesy Natalie Tsang.

Earlier this year a student researcher in British Columbia made an interesting discovery. He was mapping locations of bobcats and lynx using photos from trail cams, phones and cameras, and found the two wildcat cousins difficult to identify. So, he asked for help.

When he asked research experts who have long-worked with both species to identify a bobcat from a lynx, he found they also had a very difficult time differentiating them from one another.

Later, after the experts identified the animals, he asked again. The second time around, the experts were still having the same problem the student was. In photos, it’s just darned hard to tell the two apart. Not only do lynx and bobcat territories overlap but, apparently, so do their identities.

It’s easy to be confused.

It’s easy to be confused.

The wildcat cousins are similar in size, weight, body shape and short tails, even though lynx have longer legs and broader footpads for walking in snow, and bobcats have short, stocky muscular legs, with hind legs slightly longer than front legs, which aid their ability to pounce on prey.

The closely related wildcat cousins’ territories overlap between lower Canada and the United States’ northern borders.

Bobcat territory is limited by snow depth to southern Canada down through the continental United States and into northern Mexico. But the lynx calls the northern forests across Canada and all of Alaska home.

Of the two wildcats, the most common is the bobcat. Current estimates put bobcat numbers between 2 1/2 and 3 1/2 million in the U.S.

Those numbers make bobcats the most common wildcat in North America. They are highly adaptable and can be found in every state and almost every climate, east to west, and north to south, border to border.

The International Society for Endangered Cats reports the lynx population remains stable, but in much lesser numbers, perhaps under a million. They also cite 200 years of records from the Hudson Bay fur companies. As you might expect, lynx population correlates to the number snowshoe hares present, the lynx’ primary prey and food source.

Both wildcats are elusive and primarily nocturnal. As for bobcats, depending on where you live, you may never see one. Interesting enough, bobcats have been found in urban environments, and these small fierce hunters are sometimes captured on game cameras.

Both wildcats are elusive and primarily nocturnal. As for bobcats, depending on where you live, you may never see one. Interesting enough, bobcats have been found in urban environments, and these small fierce hunters are sometimes captured on game cameras.

Females of both species have 1-6 kittens and then stay with them for 9 months to a year before they move on. Both wildcat cousins count rabbits and hares as primary foods, but squirrels and small mammals and birds are also part of their diets. Bobcats are fierce hunters known to routinely kill prey ten times larger than themselves, such as whitetail deer.

In some areas, bobcats are trapped for their fur, much as the way lynx have historically been trapped.

As for that graduate student’s project in British Columbia, when he gave the researchers and professors another chance to identify the wildcats in his photos, he discovered they often contradicted their own earlier identifications on their second attempts.

Moral of the story? If you’re in Canada, the odds that trail cam photo is of a lynx are as high as if you are in Texas and the wildcat on your game cam is a bobcat. Unless, of course, the lynx took a trip south.

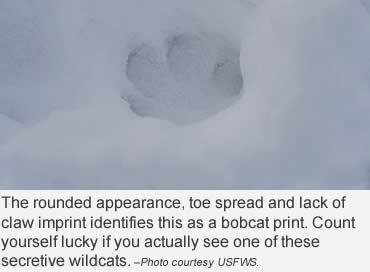

– Resources: The Wildlife Society, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Michigan Department of Natural Resources.