Help track them July 27-August 4

If you live east of the Rocky Mountains, there’s a spectacular show coming this way as millions of Monarch butterflies begin migrating south through Texas on the way to their winter home in central Mexico.

Hey, that happens every year, right? Yes, but not like it will this year.

That’s because researchers are expecting a very dramatic increase in the number of migrating butterflies, as many as 144% more! When they translated their observation estimates into numbers, that’s 300 million Monarch butterflies.

300 million migrating butterflies!

That is very encouraging news, according to Craig Wilson, senior research associate, Center of Mathematics and Science Education at Texas A&M and director of the USDA Future Scientists program, because Monarch numbers were down the past five years.

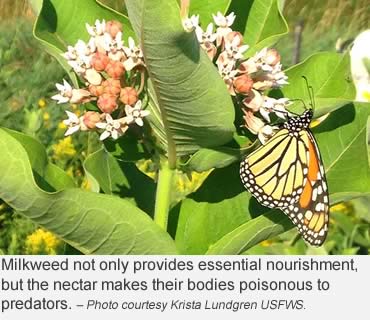

One reason for the anticipated increase in Monarch numbers is because milkweed, the essential plant Monarchs need for food after overwintering in Mexico, was in abundant supply in Texas this spring. Milkweed, a large native wildflower, is also the only plant where Monarchs will lay their eggs to continue their life cycle.

One reason for the anticipated increase in Monarch numbers is because milkweed, the essential plant Monarchs need for food after overwintering in Mexico, was in abundant supply in Texas this spring. Milkweed, a large native wildflower, is also the only plant where Monarchs will lay their eggs to continue their life cycle.

In all, four generations of Monarchs live and die, each generation reproducing the next, to complete the migration life cycle before the next fall migration. In spring, those hundreds of eggs hatch into caterpillars which only eat milkweed to live and grow and metamorphose into adult orange and black butterflies. As each female Monarch lays hundreds of eggs, the number of Monarchs grows.

Milkweed plants are critical to Monarch survival, and Texas and other states recognize the life-saving role planting and protecting native milkweed has for the life of Monarch butterflies.

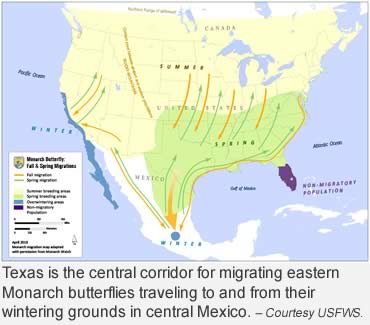

Of the North American populations of Monarch butterflies, two groups that migrate are located on either side of the Rocky Mountains. Non-migratory Monarchs are permanent residents of Florida. Monarchs west of the Rockies overwinter in both Mexico and the California coastlands, but the largest group is the eastern population.

Another thing that makes Texas so important is location, location, location.

Texas is the doorway to the grand central corridor migrating eastern Monarchs use traveling to and from overwintering grounds in central Mexico. Monarch enthusiasts —lepidopterists—are fascinated by the ability of four generations to migrate, year after year after year.

Texas is the doorway to the grand central corridor migrating eastern Monarchs use traveling to and from overwintering grounds in central Mexico. Monarch enthusiasts —lepidopterists—are fascinated by the ability of four generations to migrate, year after year after year.

Monarchs are unlike any other creature in the world. No other butterflies migrate the way they do, up to 3,000 miles at a time. Although some tropical butterflies migrate, only Monarchs make the annual 3,000-mile trip twice a year, something more common to birds or whales.

Biologists know the entire fall migration season takes 85 days, and that Monarchs fly an average of 22 miles a day but only during daylight. Larger Monarchs migrate faster than smaller ones, and the number that arrive in the northern breeding range in summer can be used to predict the eventual size of the migration generation.

Join the International Monarch Monitoring Blitz July 27-August 4

Researchers admit there is still much to learn about Monarch fall migration. Citizen scientists have been essential to recording and sharing Monarch observations, making large scale studies possible by providing data, time and resources.

In 2015, a study of citizen scientist contributions, showed 17% of 503 Monarch-focused research publications presented between 1940 and 2015 used citizen science data.

Learn how you can participate in the Third Annual International Monarch Monitoring Blitz here.

The Blitz is an international partnership asking the public to help understand Monarch and milkweed distribution throughout North America. Data gathered during the Blitz will be uploaded to the Trinational Monarch Knowledge Network, where it will be accessible for anyone for consultation and download.

The Blitz is an international partnership asking the public to help understand Monarch and milkweed distribution throughout North America. Data gathered during the Blitz will be uploaded to the Trinational Monarch Knowledge Network, where it will be accessible for anyone for consultation and download.

Monarchs and citizen scientists have shared close ties for decades. In 1940, Dr. Fred Urquhart, a zoologist from Toronto, Canada, began a research project with his wife Norah and American citizens scientists, to locate wintering sites for the Monarchs. At that time, No one knew exactly where Monarchs went when they left Texas. Volunteers spent years developing a foolproof way to tag Monarch butterfly wings.

It wasn’t until 1975 when an American textile engineer and avid naturalist Kenneth Brugger, who was working in Mexico City, responded to Dr. Urquhart’s request for volunteers to report observations of migratory Monarchs.

Brugger and his wife Catalina found a location in the volcanic mountains of Michoacán, Mexico, where they discovered masses and masses of butterflies, answering a long-asked question of where the butterflies rested during winter.

The long-awaited discovery brought joy to researchers and triggered even more unanswered questions for Monarch enthusiasts.

The butterflies congregate in an ancient oyamel fir forest in the high-altitude mountains of Michoacán. Once the location was known the area became a popular site for tourists. However, the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve is now a protected 200-square mile area, which was recognized by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as a World Heritage site in 2008.

–Resources: Texas A&M Today, March 2019; United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.