Photo: Frogs like this Blanchard’s cricket frog call as part of their courtship, as an army of volunteers listen for their calls in wetlands, marshes, lakes and rivers.

If it’s April in Wisconsin, it’s time to count frogs and toads.

Each spring for the past 35 years a small army of citizen scientists—or froggers, as they call themselves—head into the darkness to survey seasonal wetlands, marshes, lakes and rivers to help Department of Natural Resources conservation biologists document the breeding calls of frogs and toads throughout Wisconsin.

"Once again, it's time for volunteers to lend us their ears," says Andrew Badje, the conservation biologist who coordinates the Wisconsin Frog and Toad Survey. "The information volunteers provide is essential to monitoring and conserving frog and toads in Wisconsin."

Volunteers participate in three separate but related efforts.

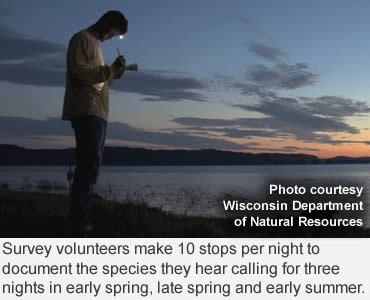

In the traditional survey, volunteers drive along a pre-set route for three nights, once each in early spring, late spring and early summer. They make 10 stops per night, or five minutes at each site, and document the species heard calling and the relative abundance of each species.

In the traditional survey, volunteers drive along a pre-set route for three nights, once each in early spring, late spring and early summer. They make 10 stops per night, or five minutes at each site, and document the species heard calling and the relative abundance of each species.

Phenology surveys, which focus on biological events such as hibernation, reproduction and migration, help monitor when frogs and toads first start calling in spring and summer. Volunteers monitor one wetland throughout the frog calling season and record data as often as possible for five minutes per night.

Other volunteers are involved in a special survey of mink frogs, which often call in the daytime. Those volunteers listen twice during the day and twice at night along set routes in June and early July.

The successful citizen scientist survey program began 1984 amid concerns of declining populations of several species of frogs.

Through the survey, these volunteers have helped conservation biologists define the distribution, status, and population trends of all 12 frog and toad species in the state.

"Our froggers have also really become advocates for frogs and toads," Badje says. "They survey upward of four routes in all corners of the state, bring their children and grandchildren on fun nighttime frog calling excursions, and provide numerous frog and toad educational presentations at local libraries and nature centers.

"A few hardy uberfroggers have even been surveying for 38 years, longer than I've been alive," Badje says. "With this level of enthusiasm, there is no doubt why this survey is the longest running citizen science amphibian calling survey in North America."

Since volunteers started collecting data in 1984, they've spent more than 9,200 nights surveying 91,000 sites, Badje says. "Without the level of monitoring volunteers can help provide, DNR would have a more difficult time assessing how well our current conservation measures are working."

Since volunteers started collecting data in 1984, they've spent more than 9,200 nights surveying 91,000 sites, Badje says. "Without the level of monitoring volunteers can help provide, DNR would have a more difficult time assessing how well our current conservation measures are working."

Volunteers are currently documenting the highest levels of American bullfrogs and Blanchard's cricket frogs since the survey began, a sign that proactive conservation measures for these two species are likely paying off.

Volunteers have been instrumental in documenting new populations of Blanchard's cricket frogs along the Mississippi River in recent years, and in places they haven't been documented in over 30 years.

And volunteer data has documented a long-term decline for the northern leopard frog over the 35-year survey, while showing that spring peepers, boreal chorus frogs and green frogs have been on more stable paths since the survey began.

The Wisconsin Frog and Toad Survey is a citizen-based monitoring program coordinated by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources in cooperation with the U.S. Geological Survey and the North American Amphibian Monitoring Program. Read more about the survey and its results here.

Visit the Wisconsin Frog and Toad Survey website here.

—By Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Wisconsin Frog and Toad Survey