A busy northwest Georgia bridge and the massive colony of bats that call it home are both better off thanks to recent work that preserved the structure and its wildlife.

The Interstate 75 bridge near Calhoun averages 72,000 vehicles a day. Yet it doubles as the largest known bridge-roost for bats in the state, according to Katrina Morris, senior wildlife biologist, who leads bat research for the Georgia Department of Natural Resources.

“Thousands of big brown and Brazilian free-tailed bats are under the bridge year-round, using it for shelter, hibernation and raising their young,” Morris said.

The combination of an interstate infrastructure and protected mammals posed a challenge for the Department of Transportation.

How could they complete required maintenance—in this case, replacing expansion joints and preserving the six-lane deck with a protective coating—while sparing the roost and the bats crowded into the bridge joints underneath?

The solution turned out to be efficient and effective, said Department of Transportation Ecology Special Projects Coordinator Sujai Veeramachaneni.

The solution turned out to be efficient and effective, said Department of Transportation Ecology Special Projects Coordinator Sujai Veeramachaneni.

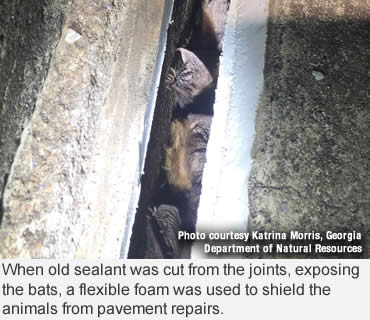

When old sealant was cut from the joints, exposing the bats, workers temporarily filled the openings with a flexible foam called backer rod to shield the animals from the sprayed-on copolymer overlay and construction debris.

Georgia’s DOT staff also mapped out plans with DNR and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service personnel to ensure the bats were monitored on-site during the project, day and night. The work was finished Oct. 4.

Morris said some of the bats were so reluctant to move from the bridge joints, she had to nudge them away from the road surface with a yardstick so workers could remove the sealant and later saw the joint edges smooth before re-sealing the openings.

Veeramachaneni said Georgia DOT does this type of maintenance each year on bridges statewide. Some have bats roosting on them, which can complicate projects.

“By testing the efficacy of backer rod . . . we now have a new tool that will help minimize harm to bats,” he said. “This tool can be used on a number of similar projects to minimize the impact on bats and ensure that projects are constructed in an environmentally sustainable manner.”

“By testing the efficacy of backer rod . . . we now have a new tool that will help minimize harm to bats,” he said. “This tool can be used on a number of similar projects to minimize the impact on bats and ensure that projects are constructed in an environmentally sustainable manner.”

That balance benefits an imperiled group of mammals.

Up to 31 percent of North America’s bat species are at risk, according to a review published in 2017 in the journal Biological Conservation. Habitat loss and white-nose syndrome are the key threats to bats.

White-nose syndrome is a fast-spreading disease that has killed millions of bats in the United States, and ravaged populations in north Georgia since it was first documented in the state in 2013.

The decline in the number of bats has undercut the vital roles bats fill: eating insects, serving as prey and adding nutrients to cave habitats.

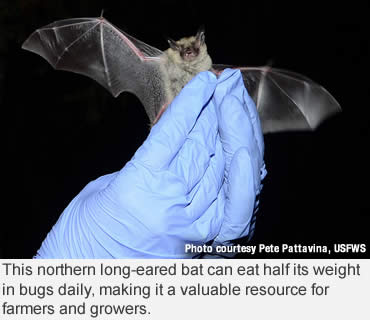

One bat can eat half its weight in insects in a night. Losing the natural pest-control services they provide could cost agriculture on this continent an estimated $3.7 billion to $53 billion a year.

The Calhoun bridge is within the ranges of Indiana, gray and northern long-eared bats, all federally-listed species, though none have been documented at the site.

In Georgia, bats are found on about 10 percent of bridges. That is why the state’s DOT has joined with DNR to factor bats into bridgework across Georgia.

Morris called it “a great example of working together to prevent harm to bats within DOT right of ways.”

The DNR and Eco-Tech Consultants Inc. are also testing the use of sound to deter bats from bridges when maintenance and other construction projects are being done, she said.

Through its Wildlife Conservation Section, Georgia DNR conserves rare and other native wildlife species not legally fished for or hunted, as well as rare plants and natural habitats. This work depends primarily on grants, contributions and fundraisers, such as the eagle and hummingbird license plates.

For more information about Georgia’s efforts to conserve nongame wildlife, click here.

—By Georgia Department of Natural Resources

Earlier this year, researchers discovered the fungus responsible for white-nose syndrome is highly sensitive to UV light exposure. It could be one of the answers to ending the deadly disease. Read more about it here.