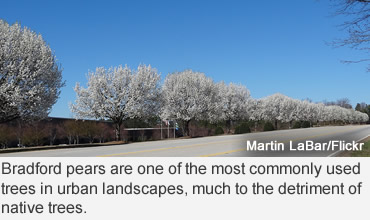

Photo: Beautiful blossoms on beautiful trees have an ugly, invasive impact on native trees.

Spring tree-planting is a great family activity, and it’s fun to watch the tree you’ve planted grow through the years.

You may even know the kind of tree you want. It’ll be the first to flower in the spring, its leaves will turn into a fantastic blaze of orange and red in the fall, it’ll grow quickly, and have a beautiful shape.

But, if you’re thinking about a Bradford pear tree, please stop. It is a beautiful tree, but it’s also an invasive menace, and the menace is growing.

Arborists, foresters and natural resources scientists strongly discourage planting Bradford pear trees, even though some tree nurseries continue to sell them.

The trees have been banned in the state of Ohio and two American cities—Charlotte, North Carolina, and Pittsburg, Pennsylvania. Most states list it as an invasive species.

Why? It’s another tragic story of good intentions gone wrong.

So many Bradford pear trees have been planted since the U.S. Department of Agriculture introduced it in 1964, they are crowding out native trees in half of the United States.

Twenty-five states are currently battling this dangerous reproductive tree. It’s impossible to ignore the thousands planted in urban and suburban neighborhoods to create photogenic entrances and boulevards.

Twenty-five states are currently battling this dangerous reproductive tree. It’s impossible to ignore the thousands planted in urban and suburban neighborhoods to create photogenic entrances and boulevards.

Once considered a sterile tree (producing no fruit), scientists since have learned it cross-pollinates with other trees and other species, creating genetic damage to native trees.

Arborists have also discovered Bradford pear offspring revert to their ancient Chinese Callery pear origins, and many now produce wicked 4-inch and larger thorns. Of the various cultivars planted, some cross pollinate and produce viable seed.

Birds eat the fruit and distribute the seeds across the landscape. Because Bradford pears leaf out early that helps them compete with native grasses, wildflowers, shrubs and young trees, according to Wendy Sangster, an urban forester for the Missouri Department of Conservation.

The Bradford pear is adaptable to many soil and shade conditions and has a high tolerance to drought. “But, it’s not a good tree because they’re not strong,” Sangster explained. “They don’t stand up well in storms and limbs break easily.”

Structural weakness is not its only flaw. Those beautiful spring blossoms emit a strong rotten fish odor.

Structural weakness is not its only flaw. Those beautiful spring blossoms emit a strong rotten fish odor.

The trees have a relatively short lifespan of 20 to 30 years, and in many areas of the country, if they haven’t been removed, they will need to be replaced. That’s why property owners and managers are being asked to use native alternatives when they plant new trees this spring.

“Over time different varieties of pear have cross-pollinated in our urban areas, allowing them to spread rapidly to our natural resources,” says Megan Abraham, director of the Indiana Department of Natural Resources Division of Entomology and Plant Pathology.

Carrie Tauscher, urban forestry coordinator with the Indiana DNR Division of Forestry, says the evidence of the trees’ rapid spread is easy to see.

“Just take a look for glossy leaved, egg-shaped trees in highway interchanges,” she said. “It’s common to find them in unknown areas under utility lines and in lots and fields initially cleared for construction that are then left fallow.”

Like other invasives, the introduction of the Bradford pear in America began as a way to combat a problem—fire blight in the common pear tree in the Northwest. In the early 1900s, the fatal disease was being spread by pollinators, severely damaging almost all of the pear crop.

Growers began to look for root stock resistant to the blight and found hope in the seeds collected by explorers and missionaries who traveled in China. After a couple of decades of growth and field tests, Callery pear stock was introduced to growers as a good solution to the fire blight problem.

The tree’s original purpose as breeding root stock was successful, so successful that following years of research, the Unites States Department of Agriculture began promoting the ornamental Bradford Pear. That was 1964, and the tree had been renamed for a horticulturalist at the USDA Plant Introduction Station.

As the tree’s popularity grew, nurseries developed their own cultivars, all making them highly tolerant and able to flourish in urban locations. In 2005, one Callery cultivar was named the Urban Tree of the Year by the Society of Municipal Arborists, now a regrettable choice.

Two decades of growth revealed the invasive nature of the tree in newly restored wetland prairies. Currently, arborists offer advice on Bradford/Callery pear tree removal and how to stop regrowth.

The task now is to spread the good word about the bad results from planting a Bradford pear tree.

Resources: Missouri Department of Conservation, Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Ohio Invasive Plants Council, Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, BioScience Vol. 57, Issue 11, Culley and Hardiman, The Beginnings of a New Invasive Plant: A History of the Ornamental Callery Pear in the United States.