During late summer, the young skunks begin to venture out under the watchful eye of their mothers. Just as children head back to the classrooms for a new school year, in the wild, young skunks are on the move and now out on their own.

Hunters of all ages making late summer visits to the woods may encounter this smelliest of mammals, so caution is encouraged.

The skunk’s reputation and odor usually precedes its presence.

Pioneers called this small black and white animal a polecat, but the Algonquin Indians are the people who gave it the name everyone uses today—skunk.

Skunks are found everywhere in North America, and typically live between two and four years.

The most common skunk species is the striped skunk, which is found from southern half of Canada to the northernmost parts of Mexico and throughout the continental United States.

Striped skunks locate their dens along forest borders, brushy field corners, fencerows and open grassy fields broken by wooded ravines and rocky outcrops, where permanent water is nearby.

Striped skunks locate their dens along forest borders, brushy field corners, fencerows and open grassy fields broken by wooded ravines and rocky outcrops, where permanent water is nearby.

A skunk typically builds its den in the ground but, occasionally a den will be found in a stump, refuse dump, cave, rock pile, a crevice in a cliff, a farm building, wood pile or haystack.

To deter unwanted skunks, farmers and people who live near wooded areas try to make yards and outbuildings less accessible and attractive to them.

As weather turns colder in late autumn, skunks spend more in their dens but do not truly hibernate.

Cat-sized, skunks are interesting and valuable members of the wildlife community and, interestingly, good mousers that also help control insects. They are immune to snake venom, and are known to eat poisonous snakes like rattlesnakes.

Although skunks have very poor eyesight, they have excellent senses of smell and hearing.

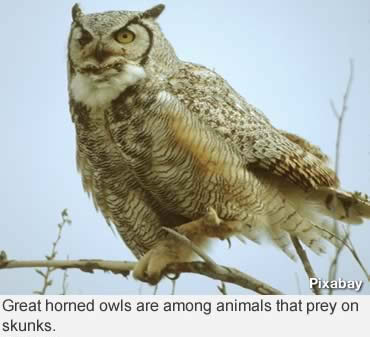

By consuming smaller animals and insects, skunks also help control undesirable populations. As scavengers, skunks help clean up the woods. Despite their foul-smelling spray, some animals, such as great horned owls, prey on skunks.

By consuming smaller animals and insects, skunks also help control undesirable populations. As scavengers, skunks help clean up the woods. Despite their foul-smelling spray, some animals, such as great horned owls, prey on skunks.

Occasionally, coyotes, badgers, foxes and bobcats attack skunks. But in the long run, skunks are not commonly preyed upon because of their ability to retaliate with smell.

Although the skunk itself is a clean animal with little body odor, it is able to produce an incredibly foul scent that is long-lasting and distinct. The scent-producing glands are under the skunk’s tail, and by using muscle control, the skunk can accurately shoot its oil-based musk up to 10 feet.

Prior to spraying, skunks usually warn intruders by stamping their feet and holding their tails high in the air. A skunk will also hiss, growl, or click its teeth together. Despite all the warnings, some animals entice the skunk to spray.

For an online field guide, visit http://on.mo.gov/2aU3boX.

— Field guide and Photo courtesy Lucas Bond, Missouri Department of Conservation.