Photo: A dangerous invader has arrived in South Carolina, the Argentine black and white tegu lizard.– Photo courtesy Dustin Smith, SCDNR.

Argentine black and white tegus first invaded Florida, the state with more invasive species than any other. Then they moved into Georgia, greatly alarming to conservationists and biologists.

On August 21, 2020, a year after their arrival in Georgia, the voracious nonnative lizards were discovered in two counties in South Carolina.

How did a lizard from South America arrive in South Carolina, Georgia and Florida? Most likely, the pet trade, and the fast-growing lizards were either released or escaped. Buying and selling tegus is legal in many states.

That is no longer true for nearby Alabama.

The Department of Conservation and Natural Resources reports the state code on nonnative animals has been amended as of Oct. 15, 2020, to prohibit selling, importing, releasing or allowing nonnatives animals into the state, including Argentine tegus.

On a national level, to assist states with the growing problem of invasive species, the Department of the Interior recently drafted a strategic plan to address the $120 billion dollar problem. It is making significant investments to fight the effects of invasives with an aggressive science-based approach to prevent, contain and control invasive species that damage native landscapes.

Currently, states affected by tegu lizards hope to raise awareness and strengthen prevention practices to avoid the spread of the species.

Currently, states affected by tegu lizards hope to raise awareness and strengthen prevention practices to avoid the spread of the species.

As a nonnative species, tegus in the wild are not protected by state wildlife laws or regulations. In Georgia, they can be killed on private property with the landowner’s permission, using legal methods in accordance with local ordinances, animal cruelty laws and safety precautions.

In all three states, any person who sees a tegu lizard in the wild is asked to contact their local conservation office to report the sighting and location. And, should one be seen in Alabama, the ACDNR requests being immediately contacted.

Why is everyone so worried?

Conservationists and biologists worry native wildlife will quickly disappear.

Tegus have no natural enemies in the Southeast. The omnivorous lizards are voracious consumers of a variety of prey such as birds, small mammals, reptiles and amphibians, fruits, vegetables, insects and eggs, and particularly eggs of ground-nesting birds like quail and turkeys, as well as eggs of alligators and turtles.

The individual lizard found in Lexington County, South Carolina was an adult female about 2.5 feet long, but adult tegus can grow up to 4 1/2-feet in length and weigh more than 10 pounds as adults. They are not venomous, and do not pose a threat to humans—just native wildlife.

“The introduction of any non-native species can have serious negative impacts on native wildlife. Black and white tegus are no exception,” said Andrew Grosse, South Carolina Department of Natural Resources herpetologist.

“Tegus mature and reproduce quickly, though most concerning may be their preference for eggs and the potential impacts to our native ground-nesting birds like turkey and quail, as well as other species such as the state-endangered gopher tortoise,” he said.

“Tegus mature and reproduce quickly, though most concerning may be their preference for eggs and the potential impacts to our native ground-nesting birds like turkey and quail, as well as other species such as the state-endangered gopher tortoise,” he said.

Conservationists in these states as well as their neighboring states are on alert, and know that public awareness and a rapid response will be the keys to stopping the spread of this dangerous nonnative species that poses an extreme threat to native wildlife.

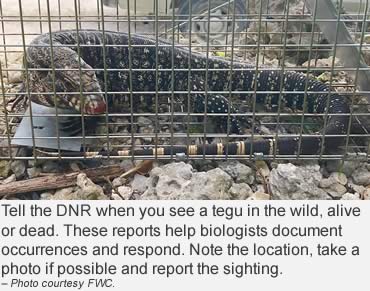

Because there are no natural predators for a tegu, they pose a severe threat to native wildlife. If you see one take a picture of it, spot its location and contact the local DNR as soon as possible.

For more information about black and white tegus, including natural history and identifying characteristics, click here.

Read our 2019 story on tegus here.

Recent news about the Department of Interior’s new program to fight invasive species can be found here.

For more about the Alabama’s new safeguards, see this story.

– Resources: Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources; Georgia Department of Natural Resources; South Carolina Department of Natural Resources; Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.