By Ralph M. Lermayer

The .22 rimfire reigns supreme for controlling pests and filling the stew pot.

It was conceived as a parlor game, a way for cooped-up people to amuse themselves, by tipping over little targets with a round not powerful enough to do any damage.

M. Flobert patented the Bulleted Breech Cap (BB Cap) in 1845. It was simply the existing musket cap with a round lead ball pressed into the rim. If you ignited the cap, the little ball would go downrange with a delightful pop. The current version of this round shoots a 20-grain ball at about 500 feet per second.

In 1857, Dan Wesson of Smith & Wesson fame looked at this little toy and had a Eureka moment. He stretched the walls of the cap a bit — to .423 inches — dropped in 4 grains of blackpowder, stuck a 29-grain bullet in the mouth, and the .22 Short was born. This one upped the ante over the Flobert cap to 1,040 fps. A little handgun was needed to shoot it, and the S&W Model 1 Revolver was the result. Now things were in motion, and the changes came fast.

In 1870, the cartridge was stretched to .595 inches. The charge increased to 5 grains with the same 29-grain bullet, and the .22 Long entered the scene.

Thinking that bigger must always be better (some things never change), the boys stretched it again. In 1880, the .22 Extra Long appeared, loaded with 6 grains of powder and a 40-grain bullet.

Thinking that bigger must always be better (some things never change), the boys stretched it again. In 1880, the .22 Extra Long appeared, loaded with 6 grains of powder and a 40-grain bullet.

Things were getting interesting in the .22 rimfire world, but in 1887, it leveled out as ballistically savvy people took a hard look at all the above iterations and selected the best of all the choices. They went back to the convenient and inexpensive length of the Long, dropped back to the 5-grain load, and matched it to the 40-grain bullet.

Power, accuracy and range were maximized, and the .22 Long Rifle was born. This is the composition of the .22 Long Rifle we all enjoy today, the same round we consume by the millions every year.

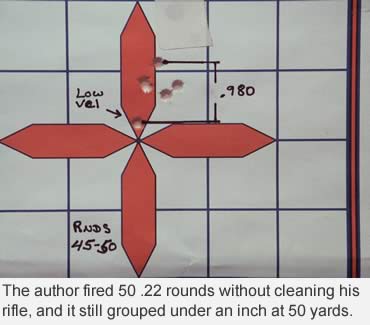

By the turn of the century, smokeless powder pretty much replaced blackpowder, although the corrosive properties of the priming compound still required thorough cleaning. Remington solved that in 1927 with the introduction of Kleenbore priming, and the .22 Long Rifle became not only pleasant and accurate to shoot, but easy to maintain as well. I know shooters who have never cleaned their .22 rimfire bores and see no reason for it. All they ask from their rifles is minute-of-rabbit, and it gives them that, clean or dirty. Others, myself included, understand that clean bores mean best accuracy.

The .22 Long Rifle bounces tin cans across dirt banks, controls pests, fills the stew pot, defends home and hearth, and competes in international and Olympic matches. Versatile, inexpensive and fun, it is the round we all began with and somehow stay with throughout a lifetime of shooting.

The Standbys

As with any product widely consumed by the buying public, variations in design and performance abound as competing companies try to grab an edge. At the core, however, some basic performance standards hold fast.

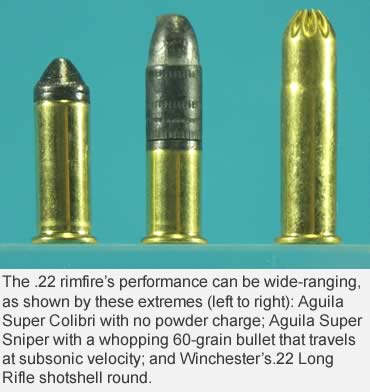

.22 BB Cap: Not exactly the same, but you can still get something very similar to Flobert’s original parlor shooter. Aguila loads a 20-grain bullet in a Long Rifle case with no powder other than the priming compound. Called the Super Colibri, it drives the little bullet at 500 fps. Make absolutely sure your barrel is squeaky clean, and check your bore after every shot because these low-energy rounds could lodge in the barrel and cause a wreck if you tried to shoot a full-power load. It’s recommended for short-barrel pistols only.

.22 BB Cap: Not exactly the same, but you can still get something very similar to Flobert’s original parlor shooter. Aguila loads a 20-grain bullet in a Long Rifle case with no powder other than the priming compound. Called the Super Colibri, it drives the little bullet at 500 fps. Make absolutely sure your barrel is squeaky clean, and check your bore after every shot because these low-energy rounds could lodge in the barrel and cause a wreck if you tried to shoot a full-power load. It’s recommended for short-barrel pistols only.

.22 CB Cap: CCI still makes them loaded with a 29-grain roundnose at about 700 fps, and Remington offers two, one with a 33-grain bullet a tad faster at 740 fps, and the newest C Bee L100, housed in the Long Rifle case with a special truncated cone hollowpoint that delivers 2x expansion at soft targets and sub-inch groups at 25 yards. Some may consider this round obsolete, but they haven’t cleared pooping pigeons out of the hayloft, kept a suburban orchard free of pests, or watched a youngster pop balloons with it.

.22 Short: Available from several sources, the standby load here is a 29-grain bullet, either all lead or copper plated, with a choice of roundnose or slight hollowpoint. Velocities run an average of 1,080 fps with some loads from Fiochi and CCI running down in the 600 to 700 fps range. Those low- power options are probably meant for ultra-quiet applications.

.22 Long: You can still get the 29-grain loading from CCI and Winchester, but I can’t imagine why anyone would want it. Interestingly, the two choices from CCI drive the 29-grain bullet at either 700 fps or at about 1,180 fps, and the single Winchester load at 700 fps. Fun to have, I guess, but with the ends covered (Short and Long Rifle), this one serves a questionable purpose.

.22 Long Rifle: Here, the choices are staggering. Fifteen different manufacturers offer bullet weights of 30, 31, 32, 33, 36, 37, 38, 48, 50 and a whopping 60 grains from Aquila in their subsonic offering. These bullets come in lead, copper jacketed or solid, and your choices expand further to roundnose, truncated or a variety of hollowpoints. Velocity runs from the hyper-fast choices like Stingers, Yellow Jackets and Zappers at 1,700 fps down to the subsonic squeakers from Remington, Lapua, PMC, Winchester and Aguila. Add to the mix shotshell loads designed to dispatch close vermin and snakes, and the choices expand further. Today’s .22 Long Rifle is a chameleon.

Yet Another Stretch

Yet Another Stretch

In 1959, horsepower for the .22 rimfire was once again increased. Winchester stretched the case to a full 1.052 inches and added enough powder to drive a 40-grain bullet to nearly 2,000 fps.

Obviously, this load developed substantially more pressure than any existing .22 Long Rifle, so Winchester had to make sure it couldn’t find its way into a standard Long Rifle action. To do this, they increased the bullet diameter of the new Winchester Magnum Rimfire (WMR) by 0.001 to .224 and thickened the case. The 40-grain bullet is the WMR standard, but both Federal and CCI are offering 30- or 50-grain choices should more speed or punch be required. Much more powerful than the .22 Long Rifle, the .22 WMR is the top choice for those cruising the timber or working a trap line.

Putting the Squeeze On

We’ve watched the little .22 go from its diminutive BB Cap to the powerful .22 WMR, but it’s not likely we’ll see more power jammed into the rimfire lineup. One of the attributes that makes the .22 rimfire so popular also limits it power. Without a primer, the firing pin must crush the rim to detonate the priming compound and make it go off. To safely add power, we would have to increase the pressure, and to do that, we would need thicker, stronger brass with a thicker rim to contain it.

Indenting a beefier rim would take a mega-muscle firing pin — and to what end?

The centerfire world picks up quite nicely after the .22 WMR with the likes of the .22 Hornet.

While more power may not be the direction of growth for the .22 rimfire, we can still neck it down, and neck it down we did!

5mm Remington: A rimfire case about 1.020 inches long, necked down to drive a .204-diameter, 38-grain bullet at 2,100 fps, the 5mm Rem was a great idea.

Remington brought it out in 1970, chambered two rifles for it, built about 50,000 rifles, and then left 50,000 owners high and dry when they discontinued production in 1982.

This was and is a good round, exceeding the .22 mag by several hundred feet per second with more terminal energy. Pressure, however, runs to near centerfire levels at 33,000 psi, so action strength might have been the significant factor in killing the round.

In 2008, Aguila of Mexico announced the reintroduction of 5mm Remington ammo.

The Minis

.17 HMR: In 2002, Hornady took the standard .22 WMR case, which they were tooled up to build by the millions, and necked it down to .172 inch. They loaded it with a 17-grain V-Max bullet and claimed a muzzle velocity of 2,550 fps. Unlike Remington, who chose the keep the 5mm Remington proprietary, Hornady let any manufacturer chamber the .17 HMR, ensuring lots of available rifles. This set the rimfire world on fire.

This flat-shooting rimfire is capable of delivering half-inch groups at 100 yards and well under 2 inches at 200 yards in the right rifles. It shoots flatter and faster than the .22 magnum, and is a true 200-yard rimfire. Today, you’re hard-pressed to find any manufacturer that doesn’t make a .17 HMR. It’s a super round that will be with us for as long as there are plinkers and pests.

.17 Hornady Mach II: If the .17 worked in the .22 WMR, why not in the standard Long Rifle case? Hornady built it, necking down the Long Rifle case to take that same 17-grain .172-caliber bullet. It kicks out of the barrel at 2,100 fps.

Several makers chambered rifles and handguns for it and waited for the orders to pour in. Didn’t happen. After a short burst of interest, shooters kind of quit the little round, and sales dropped.

My guess is there’s not much the .17 Mach II would do that the .22 LR hyper loads couldn’t do better and a whole lot cheaper. It’s fun to shoot, but doesn’t bring much new to the table. That’s probably a good thing, or someone would try to neck down the .22 Short.

The Special Stuff

Subsonic: Depending on your altitude, the speed of sound is around 1,100 fps. When a bullet exceeds that, there is a sound, a mini sonic-boom of sorts, that people simply call a gunshot. Ammunition traveling below that speed doesn’t cause that report and is deemed subsonic.

It is not, by itself, silent. In a rifle, you still hear the sounds made by the gases exiting the bore, and in a revolver, noise at the case mouth and forcing cone is still quite sharp. Overall, subsonic ammunition is far quieter.

Most of the subsonic loads use a 40-grain bullet loaded to about 1,050 fps (in a rifle). That is very close to the speed of sound threshold and quite often, given the standard velocity fluctuations, some rounds go “trans-sonic”, that is, they squeak over and create a report.

Accuracy is usually quite good with the subsonic stuff, and it’s worth noting that most match ammunition is subsonic, as breaking the sound barrier is a bit unstabling and has a negative effect on accuracy.

Other than match ammo, most subsonic loads are designed for hunting, so hollowpoints are the norm, but Aguila and PMC both offer solids. One Aguila load, the Sniper Subsonic, is particularly curious. It’s a 60-grain lead bullet that flies about 950 fps. It’s definitely a powerhouse, but you have to heed the rate of twist. The 1-in-16 twist found in most .22 rifles might not deliver optimal grouping, but try it and you might be quite surprised. For those whose pest control is at or near the edge of town, or who just want to shoot without drawing a crowd, subsonic .22s are a good choice.

.22 Shotshells

Some deem the .22 shotshell as close to useless. They have never had to pop a rodent caught in a live trap without destroying the trap, or take a venomous snake under the back porch steps. At 10 feet, most .22 rifles throw an 8-inch pattern (with flyers). Not stellar, but okay for close work. The rifling in the bore raises havoc with the shot pattern, and from handguns they really scatter. But take a .22 rimfire smoothbore (like the Mossberg or Marlin’s Garden gun), and patterns will be surprisingly good out to 15 yards.

Long Rifle shotshells usually carry about 1/15 ounce of “dust,” and CCI’s .22 magnum shotshells have a full half ounce of No. 11 shot. I always make sure there are a couple of shotshell rimfires in the belt loop whenever I carry a .22 afield. When you need one, nothing else will do the job as well.

The Big Picture

It’s an amazing little round, the .22 rimfire and its offshoots. I would bet good money that most shooting households have at least one kept close at hand and shoot it frequently, because, along with all the other attributes, they are just fun. We’ve come a long way from Flobert’s little parlor game.

Read More Articles by Ralph M. Lermayer:

• The Slug King: Ithaca’s Deerslayer is back, and this one in 20 gauge shoots as well as the original.

• A High-Tech .45-70: Rock River’s .458 SOCOM has the thump of a .45-70, but feeds in AR-15 platforms.

• The Cleaning Dilemma: Just how much scrubbing does the average rifle or shotgun need? The author feels that many hunters may be cleaning too much.

This article was published in the July 2010 edition of Buckmasters GunHunter Magazine. Subscribe today to have GunHunter delivered to your home.