Turning a so-so shooter into a MOA rifle might be easier than you think.

So you finally bought that rifle you’ve been lusting after all these years. Or maybe you inherited one from your uncle. But it’s not living up to your daydreams, not exactly shooting lights out.

Well then, tweak it.

More precisely, accurize it.

Webster’s doesn’t recognize accurize as a word, but shooters know it instantly. It describes the process of turning that so-so shooter into a tack driver. And ordinary Joes such as you and I can do it.

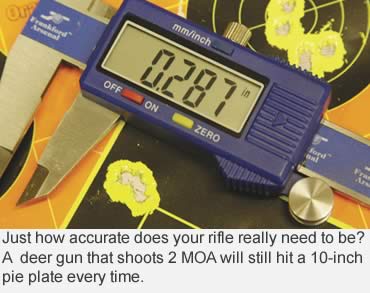

Before messing with the hardware, define accuracy for your needs. Realistically, how accurate a deer rifle do you need? Two MOA will suffice out to 300 yards. Really. If your rifle consistently puts all shots inside a 2-inch circle at 100 yards, that means it will put each shot no more than 1 inch from where you aim at 100 yards, 2 inches at 200 yards, 3 inches at 300 yards. The average deer’s chest/vital area is at least 10 inches in diameter. Aim for its center, and you aren’t going to miss if your bullet lands 3 inches from where you aimed. But of course, no real marksman wants to settle for a 2-MOA gun of any stripe. Coyote, woodchuck and prairie dog hunters shoot at 2- to 6-inch vital zones. Sometimes those tiny targets are 1,000 yards away. For this, 1 MOA is not good enough, and one-half MOA barely makes the grade. So you set your level of accuracy. Now let’s review how to achieve it.

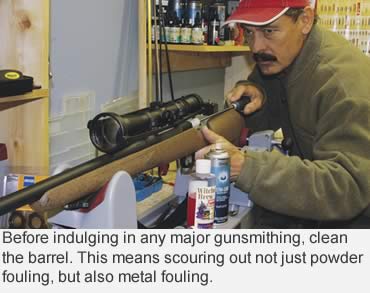

First, clean the barrel of metal fouling before firing for group size. This simple procedure has turned fouled, 3 MOA rifles into 1-MOA death rays. Use a copper-removing solvent (CR-10, M-Pro 7, Gunslick Copper-Klenz) and vigorous scraping with a tight Brownells Brass Core Bronze Brush on a one-piece Dewey or Gunslick rod. Some shooters like 10 passes with the brush for every shot fired. I usually push and pull 50 times, adding additional solvent to the bristles every 10 passes or so before pushing out the slurry with a patch. After the black powder fouling has been removed, the slurry should come out blue. This is the oxidized copper. In rough bores, J-B Bore Compound, a fine-grit polish, helps cut through the copper fouling and speeds things up. Dab the gray paste liberally on the bore brush and work that rod. Flush this out with more copper solvent. You’re finished when, after your last treatment of solvent has worked in the barrel for five minutes, the next patch comes out white.

First, clean the barrel of metal fouling before firing for group size. This simple procedure has turned fouled, 3 MOA rifles into 1-MOA death rays. Use a copper-removing solvent (CR-10, M-Pro 7, Gunslick Copper-Klenz) and vigorous scraping with a tight Brownells Brass Core Bronze Brush on a one-piece Dewey or Gunslick rod. Some shooters like 10 passes with the brush for every shot fired. I usually push and pull 50 times, adding additional solvent to the bristles every 10 passes or so before pushing out the slurry with a patch. After the black powder fouling has been removed, the slurry should come out blue. This is the oxidized copper. In rough bores, J-B Bore Compound, a fine-grit polish, helps cut through the copper fouling and speeds things up. Dab the gray paste liberally on the bore brush and work that rod. Flush this out with more copper solvent. You’re finished when, after your last treatment of solvent has worked in the barrel for five minutes, the next patch comes out white.

Second, make darn sure it’s the rifle, not the shooter, that’s inaccurate. Believe it or not, some guys shoot offhand or off truck hoods and then complain about the rifle being inaccurate. Come on guys, let’s be fair. We must isolate the launch pad (the firearm) from jerks (that’s us) and jerking as much as possible. Use a solid bench (not a card table) and sandbags, a Caldwell Lead Sled, Harris Bipod, Shooters Ridge Gorilla Bag, MTM Shoulder Guard Rifle Rest or the like to minimize all vibration. And rest the midsection of the forearm stock, not the tip and certainly not the barrel, on the support. Barrels vibrate violently when a cartridge ignites, and touching them changes bullet impact. Don’t press down on the barrel or scope, either. Hold the forearm stock loosely, if at all, and don’t go white knuckled on the pistol grip. This will introduce torque and throw your shots. Concentrate on the sight picture, and try to pull straight back on the trigger without disturbing the rifle.

Second, make darn sure it’s the rifle, not the shooter, that’s inaccurate. Believe it or not, some guys shoot offhand or off truck hoods and then complain about the rifle being inaccurate. Come on guys, let’s be fair. We must isolate the launch pad (the firearm) from jerks (that’s us) and jerking as much as possible. Use a solid bench (not a card table) and sandbags, a Caldwell Lead Sled, Harris Bipod, Shooters Ridge Gorilla Bag, MTM Shoulder Guard Rifle Rest or the like to minimize all vibration. And rest the midsection of the forearm stock, not the tip and certainly not the barrel, on the support. Barrels vibrate violently when a cartridge ignites, and touching them changes bullet impact. Don’t press down on the barrel or scope, either. Hold the forearm stock loosely, if at all, and don’t go white knuckled on the pistol grip. This will introduce torque and throw your shots. Concentrate on the sight picture, and try to pull straight back on the trigger without disturbing the rifle.

Third, if accuracy is poor, suspect your scope and mounts first. Screws really do back out. The bases might not feel loose, but tighten them anyway. Ditto the ring screws. A dab of blue #242 LocTite prevents screw-loosening. If that doesn’t improve things, try a different scope, one you know is accurate. Yes, scopes can be inaccurate. Cheap metals can wear and stick internally. Erector tube springs can weaken and become erratic. Excessive windage or elevation adjustments can push tubes so hard against springs that they cannot hold zero shot after shot. Excessive internal adjustments to get on target means you should remount and bore sight with windage-adjustable bases (Leupold, Burris, Millett, Redfield). Scopes work best with the reticle close to dead center.

Fourth, try different ammunition/bullets. Some rifles shoot one particular recipe of case/primer/powder/bullet and no other, so experiment. Try different brands, but also different bullet weights within each brand. Ideally, you should start each test group with a clean barrel, but this isn’t mandatory. One exception might be when you test monolithic bullets such as Barnes TSX, Nosler E-Tip and Hornady GMX. They are most accurate from barrels free of other bullet fouling.

Fifth, rebalance the barrel. Browning’s BOSS does this. That cylinder at the muzzle can be turned in and out until its weight changes barrel vibrations for best accuracy. The idea is to turn the bullet loose at the split second the muzzle stops between vibration cycles. The Limbsaver De-Resonator, a rubber-like collar that slips over the barrel, works much like the BOSS. Adjust its position until you get maximum accuracy. I’ve cut group size in half with one of these. It ain’t pretty, but it’s cheap accuracy.

Fifth, rebalance the barrel. Browning’s BOSS does this. That cylinder at the muzzle can be turned in and out until its weight changes barrel vibrations for best accuracy. The idea is to turn the bullet loose at the split second the muzzle stops between vibration cycles. The Limbsaver De-Resonator, a rubber-like collar that slips over the barrel, works much like the BOSS. Adjust its position until you get maximum accuracy. I’ve cut group size in half with one of these. It ain’t pretty, but it’s cheap accuracy.

Sixth, recrown the muzzle. The bevel at the muzzle must be smooth and consistent or gases will jet around the exiting bullet unequally, destabilizing it. A gunsmith can hone this smooth and precise in seconds. Countersinking the crown protects it from further damage.

Seventh, check the rifling lands at the throat or leade. You’ll need a Hawkeye Borescope to see this internal section of the barrel just ahead of the chamber where it ramps up to the rifling. If this area is lopsided, it was reamed improperly when the barrel was chambered. A good gunsmith should be able to rechamber and straighten this out. On a used gun that has been shot hot too often, the leade might be cracked like an old concrete sidewalk, which tears bullets. A gunsmith might be able to rechamber deep enough to cut this away. Otherwise, it’s time for a new barrel.

Push that borescope deeper into the barrel to check for rust pitting. Rust damage doesn’t always ruin accuracy, but if nothing else seems to be helping, your inaccuracy is probably due to the pits, and that’s the pits. Time to rebarrel. But look on the bright side: You can change chambering or twist rate, or both. Make that boring old .308 Win into a .243 Win, .260 Rem or even a .22-250 Ackley with a 1-8 twist barrel to stabilize long, heavy bullets that resist wind deflection. Now’s the time to experiment and have some fun.

Eighth, investigate the stock and change the bedding if indicated. Stocks influence accuracy by impacting or torquing the barrel or action. If the forearm touches the barrel inconsistently, this could be the problem. To test for it, isolate the barrel from the stock (called free-floating) by laying shims cut from a Coke can under the lug and receiver. It should be just enough to raise the barrel out of the stock. Retighten the bedding screws, then test fire for groups.

If this markedly improves accuracy, you may want to float the barrel permanently. Sand the channel so none of it touches the barrel. A thickness of 20-bond typing paper should be adequate, but particularly flexible molded plastic stocks and some wood stocks may need a bit more space in case they warp or swell.

Some barrels prefer upward pressure to floating. To test for this, jam a folded business card between the forearm tip and the barrel. Push it back about an inch. Test fire for group. Add more tension (more cards), and keep testing until you discover the correct upward pressure that stabilizes your barrel for best accuracy. If this works, you can oil the cards and leave them in or replace them with a bump of epoxy. Test fire, sand down the epoxy if necessary, test fire again, etc. until reaching the desired accuracy.

Be forewarned that such pressure-point bedding can change if the stock warps.

A more consistent option might be to bed the entire barrel/channel. The thicker the layer of fiberglass/epoxy you build into the forearm, the stiffer and less changeable it should be. You may need to sand quite a bit from the channel to make room for the glass/epoxy. Brownells Acraglas bedding compound is the ticket for this.

If you’re going to glass-bed the barrel, you might as well go whole hog and glass the lug and action, too. The recoil lug in many rifles flops back and forth within the excess space cut for it in the stock — not ideal for consistency.

Stocks not cut perfectly flat or evenly where the action rides can cause significant rocking or lateral motion, and if you tighten the rear screw to stop it, you torque (bend) the action The result is the bullet enters the bore already out of line.

The cure is to glass-bed the action. Detailed instructions come with the Brownells Glasbed kit. The idea is to flatten and straighten the floor so the action anchors solidly with no twisting or bending.

If you really want to get fancy, add pillar-bedding sleeves to your glass-bedding operation. These are columns of aluminum inserted into the bedding screw holes (which must be drilled larger.) They fit tight against the action while giving the screw a solid surface on which to bed when tightened. This eliminates crushing the wood or molded plastic stock material and provides a more precise, consistent lock down.

Ninth, blueprint the action. This is serious gunsmithing work involving squaring all parts to the axis of the bore. The idea is to start every bullet perfectly centered in the bore. This can’t happen if, for instance, the barrel is not screwed perfectly straight into the action. Nor if the bolt face doesn’t close perfectly flush with the chamber. Nor if the chamber is cut crooked into the barrel.

When you hire a gunsmith to blueprint your rifle, he’ll do all of this, plus square the bolt lugs in their recesses for 100 percent even contact. Might as well have him do a trigger job while he’s at it.

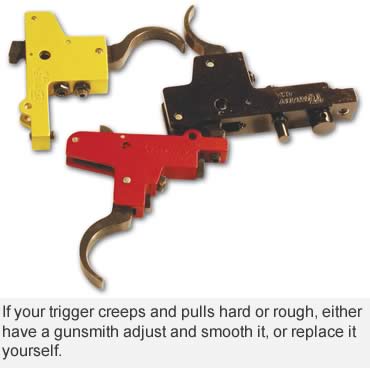

Tenth, fix the trigger! For decades rifles have been sold with “lawyer triggers,” so-called because we’ve been told gunmakers are afraid of being sued for a trigger that sets off a gun “accidentally.” This might be true, but it might also be an excuse they’ve used to reduce manufacturing costs. Gunsmiths didn’t mind this, because it gave them work. Much of this has changed since Savage came out with its superb AccuTrigger. Now virtually every gunmaker offers a vastly improved trigger. This is good, because it’s tough to squeeze accuracy from a rifle when you’re squeezing a coarse, heavy trigger so hard that you jerk the rifle off target. However, if your rifle’s trigger pulls like it’s taking a long ride over a gravel road, either have a gunsmith lighten and smooth it or replace it yourself with an adjustable, aftermarket trigger from Timney or Jewell. They are relatively easy to install with a few simple tools.

Tenth, fix the trigger! For decades rifles have been sold with “lawyer triggers,” so-called because we’ve been told gunmakers are afraid of being sued for a trigger that sets off a gun “accidentally.” This might be true, but it might also be an excuse they’ve used to reduce manufacturing costs. Gunsmiths didn’t mind this, because it gave them work. Much of this has changed since Savage came out with its superb AccuTrigger. Now virtually every gunmaker offers a vastly improved trigger. This is good, because it’s tough to squeeze accuracy from a rifle when you’re squeezing a coarse, heavy trigger so hard that you jerk the rifle off target. However, if your rifle’s trigger pulls like it’s taking a long ride over a gravel road, either have a gunsmith lighten and smooth it or replace it yourself with an adjustable, aftermarket trigger from Timney or Jewell. They are relatively easy to install with a few simple tools.

Finally, consider handloading! Yup, the final piece of the accuracy puzzle is tailoring loads to your rifle. Handloaders can neck resize or minimally size cases for a precise fit of chamber/bore. They can seat bullets at whatever distance from the lands is best for optimum accuracy. Ditto bullet selection, velocity, powder type, primer brand, etc.

If you try all of the above, and your gun still doesn’t shoot as well as you’d like, sell it and start afresh. But I can’t imagine any rifle that won’t shoot at least MOA with all the foregoing tricks applied to it. Start with the easy, inexpensive things first and work your way up to the level of accuracy you need.

This article was published in the August 2009 edition of Buckmasters GunHunter Magazine. Subscribe today to have GunHunter delivered to your home.